O nthe Mull of Kintyre there is no road vs rail

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

argument because there are no railways. People on this Scottish highland peninsula depend on road transport for everything that comas in and everything that goes out.

The area's own produce is synonomous with the highland way of life: whisky, livestock and dairy products. When the Mull's most famous resident, Paul McCartney, first flew into the main town of Campbeltown he travelled under an assumed name. The waiting taxi driver recognised him at once but refused to acknowledge celebrity: "Your taxi, Mr Smith", he said. But if Campbeltown treats the ex-Beatle as just another farmer strolling through the main street in his wellies it has a deep reverence for the malt whiskies distilled on the islands of Islay and Jura.

Haulier B Mundell at Tarbert, 30 miles outside Campbeltown, built its business on the back of the distilleries when Western Ferries linked Islay to the mainland in 1968 with a RD-RU ferry Mundell is a family business run by James Mundell and hls son Ben; James' father owned a garage and ran a couple of light CVs to transport fishjames joined the business in 1960 after demob from the army and helped develop the general haulage side oft business—until that magic moment the whisky was joined to the mainla: ferry Now Mundell has contracts with Islay distilleries—Ardbeg; Lagavull Laproaig; Bowmore; Bruichladdich; Bunnahabhain; Colila, and the one it which was the last home of author C Orwell. The distilleries produce fine hotel in Campbeltown features man: its "menu" of 150 different whiskies.

The whisky is distributed by Mw warehouses throughout Scotland an allowed the business to grow to its r

.4 size of 19 vehicles; a mixed fleet of Scania, Volvo and Daf. Tarbert is home to 10 vehicles while seven artics and two 7.5-tonners are stationed at Islay, allowing the operation to ship produce across on unhitched trailers for distribution on the island. There is a third depot at Glasgow for logistic purposes but no vehicles are based there.

Mundell does not live by whisky alone. It runs milk for the Scottish Milk Marketing Board and takes cheese down to Somerset. It also works for Islay Farmers—a co-operative of farmers with their own warehouses—and Mundell's own warehouse stores milk powder and animal feed. The closure of ICI's Scottish agricultural industries cost Mundell £110,000 a year but it has grown to a turnover of £1.5m and is largely happy to stick to its home turf.

"The only way you can expand is by taking someone else's business," reasons James Mundell." We are happy to keep what we've got." I us son Ben agrees: " To expand we would need to move to Glasgow." A glance at Mundell's back "garden"-420 acres of highland grazed by 200 sheep— makes it easy to understand why the business is happy where it is.

The local link extends to Islay's public transport service, Islay Coaches, which is run by Catherine Mundell, James' wife. Customer pressure led Mundell to go for BS5750 quality approval last October, helped by a 50% Department of Trade and Industry grant. The standard has helped the firm to win some southern business, but James Mundell is not desperate to chase rainbows: "Whatever you specialise in, that's where you make your money," he says.

Mundell and son aside, the management structure is lean. The Tarbert transport manager has been with the firm since 1948 when James' father was boss.There is another transport manager on Islay and a depot manager in Glasgow.

REMOTENESS

The remoteness ot the operation is emphasised by the extreme weather that can grip the region. "We had five vehicles stuck for eight hours in January because of the snow," says Ben, "It was so bad we didn't send vehicles up north again for two weeks."

Like everyone else, the business faces pressure on rates. "We were frightened to ask for a rates increase from customers even before the budget put up fuel," says Ben, "Hauliers are running into Islay at low rams just to keep the lorry on the road."

CM left the Mundells and their whiskies before the experience became too pleasant, pausing long enough for James to explain

why 44-tonners area bad idea: "The loads will go up but the rates will stay the same."

Agricultural haulier P McKerral at Southend is based on the southern tip of the Mull. Northern Ireland is just 13 miles across the water and car lights can be seen on a clear night.

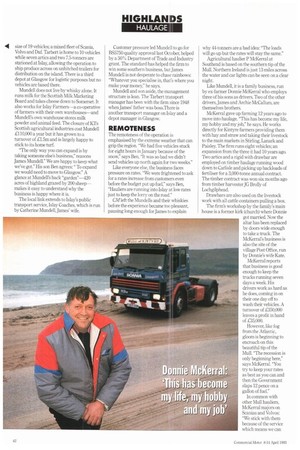

Like Mundell, it is a family business, run by ex-farmer Donnie McKerral who employs three of his sons as drivers. Two of the other drivers, James and Archie McCallum, are themselves brothers.

McKerral gave up farming 12 years ago to move into haulage. "This has become my life, my hobby and my job," he says. He works directly for Kintyre farmers providing them with hay and straw and taking their livestock to the main markets in Stirling, Lanark and Paisley. The firm runs eight vehicles; an expansion from the three it had 10 years ago. Two attics and a rigid with drawbar are employed on timber haulage running wood down to Carlisle and picking up backloads of fertiliser for a 3,000-tonne annual contract. The timber contract was won six months ago from timber harvester JG Brolly of Lochgilphead.

Drawbars are also used on the livestock work with all cattle containers pulling a box.

The firm's workshop by the family's main house is a former kirk (church) where Donnie got married. Now the altar has been replaced by doors wide enough to take a truck. The Md(erral's business is also the site of the village Post Office, run by Donnie's wife Kate.

McKerral reports that business is good enough to keep the trucks running seven days a week. His drivers work as hard as he does, coming in on their one day off to wash their vehicles. A turnover of £350,000 leaves a profit in hand of £35,000.

However, like fog from the Atlantic, gloom is beginning to encroach on this beautiful tip of the Mull. "The recession is only beginning here," says McKerral. "You try to keep your rates as best as you can and then the Government slaps 12 pence on a gallon of fuel."

In common with other Mull hauliers, McKerral majors on Scanias and Volvos: "We stick with them because of the service which means we can often get a part in an afternoon. Up here service means everything. The area is totally dependent on road haulage: nothing comes into the Mull without it" The business has seasonal dips and highs with livestock running at its peak from August to November although there is demand for hay, straw and fertiliser all year round.

McKerral experienced some immobilising moments during the cold spell. Two drivers, James McCallum and Dougie Wylie, were stuck in snow at Carrdale for two days with a load of tirnbetBut Donnie McKerral has no doubts that this is the life. He has a drink in the local pub on Saturday nights but few other diversions: "My only holiday is a couple of days off at the Highland Show."

SINGLE TRACK

Argyll Creameries runs milk and dairy products six days a week between Campbeltown and Glasgow along 140 miles of difficult road, much of it single track. Vehicles have to pull into passing places to allow others through.

Remote it may be, but this is a modern, efficient business, working for its main client, the Scottish Milk Marketing Board, and well on its way to BS5750 for food distribution. And it's all based on one vehicle; a Volvo FL10 pulling a drawbar trailer running at 32.5 tonnes.

The schedule is punishing for the vehicle but fortunately less so for the two drivers who keep it on the road. The sleeper cab's bunk is only used for storing paperwork; drivers get their overnight stops in a hotel." We book them in for a full 12 hours rest twice a week," says John Currie, director of the liquid division.

The switchovers are made on Tuesday and Thursday at Lochgilphead where the second driver sets off to Oban, unloads, drops the empty drawbar back at Lochgilphead and carries on into Campbeltown. The remainder of the load is taken off and the driver returns to Lochgilphead where he switches to a van for local deliveries. The first driver, refreshed, picks up the reins of the FL10 and his new 15hour day begins.The FL10 has clocked up 240,000km in a year.

The week begins at midnight on Sunday when the vehicle leaves Campbeltown and makes several drops en route to Cairndow. It continues into Glasgow empty and reloads with semi-skimmed milk, yoghurts and chilled food for customers back along the route and on the Mull itself. By 17:00hrs Monday the Volvo is back in Campbeltown where it is unloaded, reloaded and the fridge plugged into mains electricity. By midnight it is ready to leave again.

Drivers switch over at Inverary, halfway between Campbeltown and Glasgow. In the year Argyll has run the FL10 it has broken down only twice although the elements left it stranded on the infamous Rest and Be Thankful for 12 hours during the winter.

Currie says before the days of road transport supplies to the Mull were ferried in by steamer, and if you go back far enough stagecoaches took two days to arrive from Glasgow.

But returning to the present day, why Volvo? "We have looked at other premium trucks and there's not much to choose between them," says Currie, "It is the quality of the service that keeps us with Volvo. Customers expect us to deliver daily; there cannot be a breach in the service. We can't afford to have a truck backed against a wall waiting a week for a part."

WORKED HARD

The Volvo is certainly worked hard but it is regularly inspected and serviced every fourth weekend.

Argyll does not collect from the farmers, that is handled by the Scottish Milk Marketing Board, but it pasteurises, packs and distributes its own and other brand labelled dairy products.

Currie says that Argyll aims for higher standards than those laid down by the EC for chilled and frozen food. "The requirement of the EC regulations fall far short of what we would consider an acceptable standard," he explains, "Some of the EC standards are political compromises. We believe food should be chilled at under 4°C, but the regulations only call for 6°C. Some fooe sporing organisms can survive pasteurisation in a spore forming state they can begin to vegetate at 5°C."

Depot transport manager David MacBrayne explains how Argyll contn reefer temperature: "The cab is fitted vi Thermoprint computer which relays tI temperature of the fridge and can be cif: start and stop it. A print-out proves the was delivered at the right temperature details door opening and closing times Argyll has put fridges into some of it bigger customers' shops which its driv unlock from outside the premises, alio, night delivery. It services the isles thre, a week, sending vans across by ferry.

The main operation, delivering to GI takes about five hours including drops MacBrayne drove on the route for 18 rr and says the police tolerate speeds abo 40mph limit because of the difficult nal the journey "The roads are very narro you are used to them it's no problem, b. can be a frightening experience for passengers—if you can drive on these you can drive anywhere."

CI by Patric Curmane