MOVING HOUSE

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

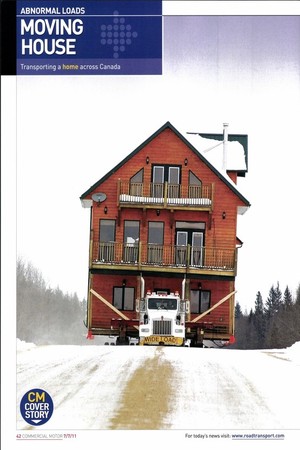

Transporting a home across Canada

For most Canadians, moving house is fairly straightforward, but when you're literally picking up your home and taking it with you across a frozen lake in temperatures of minus 25° things become a bit trickier

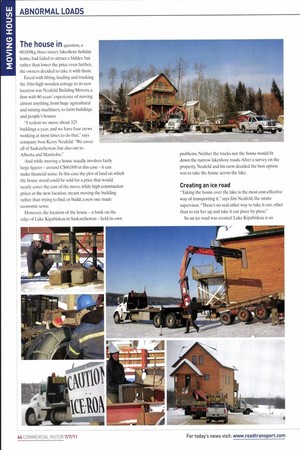

z The house in question, a 60,000kg three-storey lakeshore holiday home, had failed to attract a bidder, but rather than lower the price even further, the owners decided to take it with them.

Faced with lifting, loading and trucking the 10m-high wooden cottage to its new location was Neufeld Building Movers, a firm with 60 years' experience of moving almost anything, from huge agricultural and mining machinery, to farm buildings and people's houses.

"I reckon we move about 325 buildings a year, and we have four crews working at most times to do that," says company boss Kerry Neufeld. "We cover all of Saskatchewan, but also out to Alberta and Manitoba."

And while moving a house usually involves fairly large figures — around C$60,000 in this case — it can make financial sense. In this case the plot of land on which the house stood could be sold for a price that would nearly cover the cost of the move, while high construction prices at the new location, meant moving the building rather than trying to find, or build, a new one made economic sense.

However, the location of the house — a bank on the edge of Lake Kipabiskau in Saskatchewan — held its own problems. Neither the trucks nor the house would fit down the narrow lakeshore roads. After a survey on the property, Neufeld and his crew decided the best option was to take the house across the lake.

Creating an ice road "Taking the house over the lake is the most cost-effective way of transporting it," says Jim Neufeld, the onsite supervisor. "There's no real other way to take it out, other than to cut her up and take it out piece by piece."

So an ice road was created. Lake Kipabiskau is an idyllic water sports haven throughout the warm Canadian summer, but in winter it becomes a playground for ice-hole fishermen, cross-country skiers and skidooers.

At this point, ice road specialist Gary Kuzar was called in. Three weeks before the move, he began constructing a one-mile-long ice road, thick enough to withstand the combined weight of the house, and the machinery used to move it.

The ice was already strong enough to support 4x4 pickup trucks and cars, but Kuzar calculated it would need a further 20 inches before it would be thick enough to stop the combined weight of house and truck crashing through into the freezing water.

19 days of pumping 'Omar ploughed a rough path before employing two specially designed pumps to suck water from beneath the ice and spray it onto the surface of the lake.

"I use specially designed pumps, and add an average of 35,000 tonnes of water each day," he says. It took 19 continuous days of pumping to ensure the ice thickness grew to 47 inches.

As moving day approached, the Neufeld crew brought in a fleet of Kenworths, pickups, a Paffinger crane, dollies and specialist load-bearing equipment to ready the house for its move.

Each member of the six-man crew is proficient in a wide range of skills, from driving oversized loads and HGVs, to operating oil-powered jacks, and calculating how much weight load-bearing joints can take.

Most spend around 30% of the year away from home, preparing structures for transportation, trucking the property to new locations during the day, then staying at local motels in the evenings.

Once the belongings in the house had been removed, the crew took away its steps to make transportation easier, then added strengthening struts to support the balconies.

The crew then moved in to dig away at the basement so that the house could be raised.

They placed eight jacks under the main beams and slowly increased the oil pressure to lift the structure clear of its foundations and into mid-air.

After two days, the house had been lifted enough to allow two steel beams to be run through under its main supporting beams.

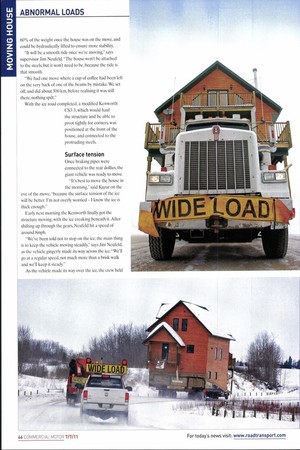

A pair of specially designed, air-cushioned dollies were brought in under the house, and placed at the rear of the property to allow the steel beams to rest in the saddle of the dolly. The two Haulin Haug dollies would take around 60% of the weight once the house was on the move, and could be hydraulically lifted to ensure more stability.

"It will be a smooth ride once we're moving," says supervisor Jim Neufeld. "The house won't be attached to the steels, but it won't need to be, because the ride is that smooth.

"We had one move where a cup of coffee had been left on the very back of one of the beams by mistake. We set off, and did about 300 km, before realising it was still there, nothing spilt."

With the ice road completed, a modified Kenworth CS3-3, which would haul the structure and be able to pivot tightly for corners, was positioned at the front of the house, and connected to the protruding steels.

Surface tension

Once braking pipes were connected to the rear dollies, the giant vehicle was ready to move. "It's best to move the house in the morning," said Kuzar on the eve of the move, "because the surface tension of the ice will be better. I'm not overly worried — I know the ice is thick enough."

Early next morning the Kenworth finally got the structure moving, with the ice creaking beneath it. After shifting up through the gears, Neufeld hit a speed of around 8mph.

"We've been told not to stop on the ice; the main thing is to keep the vehicle moving steadily," says Jim Neufeld, as the vehicle gingerly made its way across the ice. "We'll go at a regular speed, not much more than a brisk walk and we'll keep it steady."

As the vehicle made its way over the ice, the crew held onto guide ropes attached to the structure, in order to feel any sudden movements or potential lack of balance.

And despite tiny superficial cracks appearing on the surface ice, both truck and house reached the shoreline within minutes.

Then came the task of moving the vehicle up a 15-degree incline. A super-sized Western Star tow-truck was positioned at the top of the rise, planting its legs to help winch truck and house up onto flatter ground.

The Kenworth CS3 then took back control, and carefully navigated the grit trail until, late into the day, it made it to the first area of tarmac road — less than two kilometres from where the house had stood.

Negotiating electricity cables Although the plot of land the house was destined for was only 80km away, the Neufeld crew had to travel closer to 145km to avoid highways, unsuitable road surfaces and a maze of electricity cables.

And although a preordained route had been carefully planned, there were still more than 25 sets of cables needing to be cut, with five teams of technicians from the local electricity company — SaskTel — on hand the next morning. Once clear of the cables, the 10m-high house began to negotiate the farm tracks that criss-cross the flat wheat country of Saskatchewan, travelling at a steady 40km/h.

"I only have 450hp under the bonnet, but it's usually plenty for most of the things we move," says Jim Neufeld. "We rarely have any problems, although we did once have a house that slid off the steels. The truck was forced to swerve, it hit a bank and the house just slid off the side and into a field. But that was the only time."

With a pilot and tail truck in place, the house made good progress, and finally, three days after first being lifted, reached its new home — Wapiti, a skiing and hiking resort.

Here it would wait to be unloaded the following spring when the rock-hard frozen ground started to thaw. Then it would be gently lowered onto its new foundations. •