Badger Sei v Economy Record

Page 112

Page 113

Page 114

Page 115

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E.

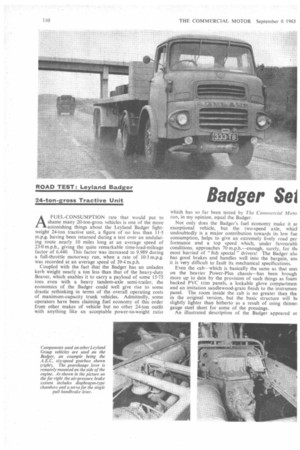

AFUEL-CONSUMPTION rate that would put to shame many 20-ton-gross vehicles is one of the more astonishing things about the Leyland Badger lightweight 24-ton tractive unit, a figure of no less than 11.5 m.p.g. having been returned during a test over an undulating route nearly 10 miles long at an average speed of 23.0 m.p.h., giving the quite remarkable time-load-mileage factor of 6,440. This factor was increased to 9,989 during a full-throttle motorway run, when a rate of 10-3 m.p.g. was recorded at an average speed of 39-4 m.p.h.

Coupled with the fact that the Badger has an unladen kerb weight nearly a ton less than that of the heavy-duty Beaver, which enables it to carry a payload of some 15.75 tons even with a heavy tandem-axle semi-trailer, the economics of the Badger could well give rise to some drastic rethinking in terms of the overall operating costs of maximum-capacity trunk vehicles. Admittedly, some operators have been claiming fuel economy of this order from other makes of vehicle but no other 24-ton outfit with anything like an acceptable power-to-weight ratio

which has so far been tested by The Commercial Moto can, in my opinion, equal the Badger.

Not only does the Badger's fuel economy make it al exceptional vehicle, but the two-speed axle, whicl undoubtedly is a major contribution towards its low fue consumption, helps to give an extremely lively road per formance and a top speed which, under favourabll conditions, approaches 70 m.p.h.—enough, surely, for th( most hurried of "fish special" drivers! The Badger Ells( has good brakes and handles well into the bargain, an( it is very difficult to fault its mechanical specifications.

Even the cab—which is basically the same as that use( on the heavier Power-Plus chassis—has been brough more up to date by the provision of such things as foam backed PVC trim panels, a lockable glove compartmen and an imitation sandlewood-grain finish to the instrumen panel. The room inside the cab is no greater than tha in the original version, but the basic structure will 13( slightly lighter than hitherto as a result of using thinnel gauge steel sheet for some of the pressings.

An illustrated description of the Badger appeared or and 65 of our June 28, 1963 issue at the time .roduction, and reference to this article will make how the weight saving has been accomplished d with the Beaver. At the time of its introduction land specification stated that the maximum net utput of the special de-rated 0.600 engine, which ily power unit fitted in the Badger, was 350 lb. ft., equent to this it was discovered that engines with number of hours running than had been achieved ad of June were delivering 375 lb. ft., and this is genuine rating. This is still, however, below the . input-torque rating of the A.E.C. gearbox, so iceLy to induce premature transmission failure.

th the Retriever, which was announced in our issue, the Badger makes use of Leyland Group ;tits already being used on other vehicles, thus that it will "fit in with existing servicing arrangeThe only exception here is the chassis frame, the nbers of which are different in section from those other Group chassis. The front axle also is not identical form in another Leyland model, but is iilar to that of the Tiger Cub passenger chassis and sign loading of 4 tons.

for any new model these days, the Badger is in one form only, there being no load-carrier and specification options are limited to a choice sets of axle ratio. The 9-ton driving axle consists Lnd case, hubs, brakes and so forth, with an Eaton piral-bevel driving head, the change for which is lly controlled. The sets of ratios are 5.14/7-02, and 6-5/8.87 to 1, the highest axle giving a lowottom-gear gradient ability of 1 in 5 and a top more than 70 m.p.h., whilst the lowest-ratio axle >pective figures of 1 in 3-9 and more than 55 m.p.h. )-00-20 tyres are standard, these being mounted on 10-stud B6.5-20 wheels with 5-6-in. offset.

Low unladen weight—for its class—is a valuable attribute of the Badger, and the tractive unit tested had a kerb weight of 4 tons 6-5 cwt., this being without spare wheel and carrier, however, as these had been removed to accommodate the fuel-test tank. The Scammell semitrailer supplied was an old friend, being the same one used for my 1961 test of a Beaver tractive unit. Its unladen weight was somewhat high. at 3 tons 19-75 cwt., and as there are tandem-axle semi-trailers available which weigh a good 10 cwt. less than this, it is obvious that the Badger's lightness enables it to handle payloads of 16.5 tons or more, depending on the Hake and type of semi-trailer used.

BRAKES Being a " Leyland-matched" product, the Scammell semi-trailer had Leyland driving-axle brakes, each one individually actuated by a front-axle size of diaphragm chamber. This is a far more effective system than that employed by Scammell on their normal heavy-duty tandem-axle models, which have a single piston-type air servo. Thus. I was not surprised that the braking efficiency of the outfit, which was grossing 24 tons 7-75-cwt., was particularly good in terms of stopping distance.

The figures detailed in the data panel were obtained with a maximum line pressure of 96 p.s.i., and on each occasion the driving wheels locked—for an average of 7 ft. from 20 m.p.h., and 35 ft. from 30 m.p.h. This locking suggests that, for its loading, the driving axle tends to be overbraked, and whilst there was no fear of the outfit jackknifing on the dry road used for the tests, instability might occur on a wet or icy road, so a reduction in the braking effort at

these wheels would probably give increased safety under adverse road conditions, with a fair chance of even shorter stopping distances on dry surfaces. Nevertheless, the figures I obtained are absolutely first-rate, and the retardation from 30 m.p.h. has so far been beaten by only one other 24-ton articulated vehicle.

In the event of footbrake failure the driver of a Badger need not give up the ghost, for tests showed that the n38 tractive-unit handbrake by itself could give a maximum deceleration (by Tapley meter) of 23 per cent from 2C m.p.h., whilst the semi-trailer hand-reaction valve produced an effect of 26 per cent when applied fully from the same speed. The combination of powerful brakes and an axle loading of less than 9 tons caused the nearside driving wheels to lock when using the tractive unit handbrake alone from 20 m.p.h., the sliding distance being up to 62 ft. igh obviously the ; of the 200-b.h.p. .ould not be expected the less-powerful the acceleration peres obtained during t were above the for this weight of ed vehicle. The -start figures were with the axle in high whole time, using third, fourth and rs, whilst the direct-drive (fifth gear) times in the lel were obtained with the axle in low ratio, hence nate speed being 39 m.p.h. Not that the Badger that sluggish a performance in direct-high: fullacceleration figures taken in this ratio combination m.p.h. upwards showed the ability to reach 20 26.0 sec., 30 in 54-5 sec. and 40 in 91.0 sec., whilst rie and transmission smoothness were good also.

HILL CLIMBING AND FADE acceleration performance does not always necesply high-speed, hill-climbing ability: much depends pread of the gear ratios. Fortunately, in the case adger tested (which had the 5.57/7.6 to 1 axle), the ead was good and the only two gearing combinalich came within 2 m.p.h. of each other were and sixth-low, all the others being sufficiently :ed out to enable high average speeds to be mainlong hilly roads. :suit was that the Badger made a very good climb dci Hill. which is 0.75-mile long and has an average of 1 in 12. The ascent was made in an ambient ure of I7°C. (63"F.) and the total climbing time in. 49 sec. This is only 1 min. 29 sec. longer than taken with the Beaver two years ago and nearly ss than the time recorded up the same slope with )us rigid eight-wheeler powered by the I,700-r.p.m.

the 0.600 diesel.

iinimum road speed on the steepest section of the between 4 and 5 m.p.h., and this was while in 3w, a combination which was in use for a total 1 min. 26 sec. At no time was there any exhaust the exhaust outlet being easy enough to check, nsverse silencer and tailpipe ahead of the front standard on the Badger. That the cooling-system is adequate was shown by the water temperature )rn 73'C. (164-F.) to only 78°C. (173°F.).

resistance was tested by coasting the outfit down with only the footbrake to keep the speed down ph. This descent took 2 min. l2 sec., and at the )f the hill a simulated crash stop was made. This a Tapley meter reading of 53 per cent, which is 5 per cent less than that recorded when the drums d. This is a very good performance for a 24-ton n a hill of this length and steepness, and indicates Badger should have ample braking reserve with es of semi-trailer.

returned the outfit up the hill and stopped it on 6.5 part, where separate tests were made of the init, semi-trailer hand-reaction valve and semiarking handbrakes. The two brakes controlled driving seat were each powerful enough to hold le easily, but the semi-trailer parking brake proved capable of restraining backward motion. Followa restart was carried out in bottom-high, this full throttle but with the get-away being smooth. own the hill each of the three handbrakes would vehicle when applied separately, and a reversetrt was made without any difficulty. FUEL CONSUMPTION Three of the four fuel-consumption figures reproduced in the data panel were obtained over an undulating route 9.5 miles in length, which demanded a considerable amount of gearwork when running at the full load. In the light of this, the consumption rates obtained are quite exceptional, even the " unladen " result (during the course of which the semi-trailer was carrying some fairly heavy pieces of timber which had been used to secure the test weights) showing commendable economy. The m.p.g. figures resulting from these tests show that an experienced trunk driver should get more than II m.p.g. with his vehicle continuously laden, whilst if 50 per cent of the operational mileage has to be covered unladen the overall fuel figure should be better than 14 m.p.g. Continuous full-throttle operation under motorway conditions should not have any adverse affect on the Badger's economy, for a test made along the Lancaster by-pass over a distance of 23.6 miles gave a consumption rate of 10-3

m.p.g. for the high average speed of 39.4 m.p.h. This stretch of motorway is by no means-as conducive to good fuel and average-speed figures as more gently undulating motorways, so the performance is most satisfactory.

RIDE AND CONTROL In view of its extremely short wheelbase, the Badger rides quite well. With this length of tractive unit pitching is virtually unavoidable, so the Badger does pitch, but not to anything like the degree I had anticipated before I started to travel in the vehicle. Furthermore, the quality of the ride is not changed to any detrimental degree when the semi-trailer is unladen.

In the same way, however, the steering characteristics do not vary much between the laden and unladen conditions, though this is not really so surprising as hardly any of the payload is imposed on the front axle. Thus. the heaviness of the steering when running laden is still present when unladen, and there is also a tendency to wander, which makes it feel at times as though the semitrailer is taking charge. Fortunately, the steering is not heavy when reversing slowly, so shunting is no trouble.

The engine behaved extremely well throughout the test and proved to be a very willing unit. The noise level in the cab was by no means excessive, and the test vehicle had the standard Power-Plus cab, whereas production Badgers should have the de-luxe model with plenty of foam-backed PVC to help absorb much of the engine noise. The gearbox is pleasant to use, and fast upward changes are possible with a bit of skill, the main limitation being the slowness with which the engine revs die down.

Occasionally it was found difficult to engage a forward gear after the box had been in reverse, but presumably this was something to do with the remote linkage. The brakes had enough feel to give positive control, both laden and unladen, but use of the semi-trailer hand-reaction valve by itself revealed traces of delay for which the tractive unit's system could hardly be blamed.

In standard form the Badger has a chassis-cab list price of £2,925, this being subject to the usual discounts.