Bigger Buses to Speed up Opera' don D ISCUSSING the influence

Page 13

Page 14

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

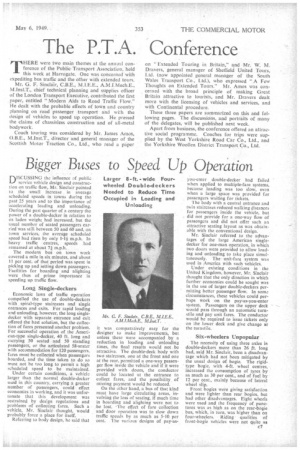

of public service vehicle design and construction on traffic flow, Mr. Sinclair pointed to the small increase in average scheduled speeds in towns during the past 25 years and to the importance of accelerating loading and unloading. During the past quarter of a century the power of a double-decker in relation to its laden weight had increased, but the usual number of seated passengers carried was still between 50 and 60 and, on town services, the average scheduled speed had risen by only 1-13 m.p.h. In heavy traffic centres, speeds had remained at about 7f m.p.h.

The modern bus on town work covered a mile in six minutes, and about 11 per cent, of that period was spent in picking up and setting down passengers. Facilities for boarding and alighting were thus of prime importance in speeding up traffic flow.

Loug Single-deckers Economic laws of traffic operation compelled the use of double-deckers with spiral-type staircases and single entrances and exits. For rapid loading and unloading, however, the long singledecker with separate entrance and exit offered the best solution, but the collection of fares presented another problem. For successful operation of the American-type single-decker, 40 ft. long and carrying 50 seated and 50 standing passengers, or the articulated 58-seater with accommodation for 120 passengers, fares must be collected when passengers boarded, and the time taken to do so must not be too long to permit a high scheduled speed to be maintained.

Under certain conditions, a vehicle larger than the normal double-decker used in this country, carrying a greater number of passengers, could effect economies in working, and it was unfortunate that this development was restrained by design regulations and problems of collecting fares. Such a vehicle, Mr. Sinclair thought, would probably force a place for itself.

Referring to body design, he said that

it was comparatively easy for the designer to make improvements, but unless these were accompanied by a reduction in loading and unloading times, the final results would not _ be attractive. The double-deck body with two staircases, one at the front and one at the rear, permitted a one-way passenger flow inside the vehicle and if it were provided with doors, the conductor could be located at the entrance to collect fares, and the possibility of missing payment would be reduced.

On the other hand, a bus of that kind must have large circulating areas, involving the loss of seating, if much time in boarding and alighting were not to be lost. -The effect of fare collection and door operation was to slow down traffic speeds by as much as 5-10 per cent. The various designs of pay-as

you-enter double-decker had failed when applied to multiple-fare systems, because loading was too slow, even when a large space was provided for passengers waiting for tickets.

The body with a central entrance and twin staircases reduced walking distances for passengers inside the vehicle, but did not provide for a one-way flow of passengers and did not offer such an attractive seating layout as was obtainable with the conventional design.

Mr. Sinclair referred to the advantages of the large American singledecker for one-man operation, in which two doors were provided to allow loading and unloading to take place simultaneously. The unit-fare system was used in America with such vehicles.

Under existing conditions in the United Kingdom, however, Mr. Sinclair thought that the only direction in which further economies could be sought was in the use of larger double-deckers permitting better passenger flow. In some circumstances, these vehicles could perhaps work on the pay-as-you-enter system, Passengers on the upper deck would pass through an automatic turnstile and pay unit fares. The conductor would be required to issue tickets only on the lower deck and give change at the turnstile.

Six-wheelers Unpopular The necessity of using three axles in double-deckers more than 26 ft. long had, said Mr. Sinclair, been a disadvantage whieh had not been mitigated by the usual design of bogie. The rigid' type bogie, with 4-ft. wheel centres, increased the consumption of tyres by as much as 30 per cent., and of fuel by 12 per cent., mainly because of lateral wheel slip.

Front bogies were giving satisfaction and were lighter than rear bogies, but had other disadvantages. Eight wheels were used and the frequency of punctures was as high as on the rear-bogie bus, which, in turn, was higher than on four-wheelers. Riding qualities of front-bogie vehicles were not quite as

good as those of multi-wheelers with rear bogies. The solution of the probblem of the larger double-decker would be a two-axled machine 8 ft. wide, To take advantage of the full-fronted design in buses and to make the best use of body space;an underfloor engine was essential, said Mr. Sinclair.

On the subject of alternative methods of construction, Mr. Sinclair declared that the change from timber to metal in bus bodybuilding provided an opportunity of going over to chassisless construction. The integral-type vehicle offered greater flexibility in body design, as it affected cab and platform size, window spacing and other features.

The box-like body could be stressed as a structure and each body member of the structure could be similarly stressed, so that it was important that the physical values of the material used should not vary beyond certain limits. With metals, greater accuracy in physical values was obtainable than, with timber. The longitudinal forces of acceleration and retardation, and the lateral stresses caused by centrifugal forces on curves, made up the working loads of the structure, and the best use could be made of materials to withstand these stresses, and to reduce weight, by designing the vehicle as a whole.

The splitting of the chassis and body for overhaul was outmoded, Mr. Sinclair said, and the engine and other mechanical parts could be dismantled at a garage, repaired in a central engineering works and delivered to the garage for re-assembly. The chassisless vehicle fitted into this scheme of maintenance, Composite metal and wood construction was only a halfway stage in design. Techniques would be developed in the use solely of metals, whether steel or aluminium alloys, selection resting on economics. With fuel at its present price and allowing for buses operating at average scheduled speeds in towns. every hundredweight saved in unladen weight justified the payment of another £20 in capital cost of a bus.

Ignorance of Light Metals

Ignorance of the properties and methods of working aluminium alloys for vehicle construction was, Mr. Sinclair thought, responsib4e for much unwarrantable prejudice for and against them in the road transport industry. By taking full advantage of metal construction in buses, fewer man-hours would be required in their production, and a lighter and stronger body, offering lower operating and maintenance costs, could be obtained.

The speaker thought that independent front suspension might become general on buses: At the rear, however, he said, the springs acted as torque and thrust members in addition to carrying the load, and to replace them with independent suspension would introduce undesirable .mechanical complications.Independent front suspension was particularly applicable to light chassisless . vehicles and good results had so far been obtained during road tests.

Criticizing engine starters, he said that there had been a lack of fundamental research into their mechanics. The commo n, but unmechanical, method of engaging a revolving pinion into a stationary gear demanded too much for satisfactory operation.

In dealing with modern aids to road traffic flow, Mr. Sinclair described the effects of town and country planning on transport, and dealt with high-speed motor roads and vehicle-actuated signals. He said that public transport services must be given ready access to the main traffic objectives in towns, and public service vehicles should receive treatment at least equal to that of the private car. Any relegation of transport services to subsidiary routes away from the principal streets in a town or city would be against the public interest.

In rebuilt and new towns, Mr. Sinclair thought, journeys to work and play would shorten, but would become more frequent. The attractions of the existing towns and cities would, however, continue, and many long-distance journeys would still be made despite inter-siting of factories and homes.