Brakes Put The New Comet Ahead

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

-,atest Leyland Comet 12-tonier has air brakes which give .emarkably safe retardation tharaeteristies, whilst 0.370 liesel engine provides lively ierformance with good fnel

economy By John F. Moo'

A.M.I.R.T.E.

NEARLY eight years ago I went to Leyland to test the first Leyland Comet 90 " Side-type " forwardcontrol 11 ton 12 cwt. gross four-wheeler and at the same time Laurence 1. Cotton—who was then Technical Editor—travelled with me to test a Leyland 3-tonner which had been built in about 1908. There is about the same resemblance between the 1908 3-tonner and the 1954 Comet as there is between the 1954 Comet and the 1962 version which 1 tested the other day, so great have been the improvements to the Comet in the past eight years.

The latest range of Leyland Comets—the CS3. models— are described on the preceding page. These new models differ from their immediate predecessors in that they have full air-pressure braking, making them unique among current British 12-ton-gross designs. The braking performance given by this new braking system makes the Comet unique also, for the model that [tested was brought to rest from 30 m.p.h. in 43.5 ft. without any harshness or lack of directional control. This is a remarkable figure for a vehicle of this weight, and should successfully silence those critics of previous Comet models who saw reason to be dissatisfied with the rather small-area, vacuumhydraulic brakes of the earlier versions.

Not having tested a Comet between this present one and the model 1 tried in 1954, I cannot make comparisons between this latest 12C, series and the models which immediately preceded it. Comparisons between the 1962 and 1954 versions—other than those concerned with braking—are most revealing, however. To begin with, the original Comet 90 forward-control chassis was restricted to a gross weight of 11 tons 12 cwt., compared with the 12 tons of the current model. The 1954 chassis had the original 0.350 diesel engine, the maximum output of which was 90 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m., with a peak torque rating of 240 lb.-ft. at 1,300 r.p.m., whilst the latest version has the 0.370 engine with a net output of 110 b.h.p. at 2,400 r.p.m. and a torque peak of 272 lb.-ft. at 1,000 r.p.m.

The vehicles tested in 1954 had what was then a new five-speed direct-top constant-mesh gearbox, whereas the one tested recently had the latest Leyland-Albion five-speed box, phis optional sixth overdrive, and in place of the spiral-bevel rear axle of the earlier design, the latest model has a Leyland-Albion double-reduction unit, with the

option of Eaton two-speed gearing. Whilst the chassis frame and suspension have not been changed a great deal, since I last tested the Cornet a completely new ail-steel cab has been adopted.

These physical differences do not, however, give an accurate indication of how much the Comet's performance has improved over the years. For instance, the 1954 model took 57 ft. to stop from 37 m.p.h.-13.5 ft. more than the current heavier version—whilst 10.6 seconds have been knocked off the time taken to accelerate from a standstill to 30 m.p.h.

The road-test figures which probably interest operators most are those relating to fuel consumption, and here again the new Comet runs rings round its forerunners: the best figure that could be obtained on a level road in 1954 was 14 m.p.g.: over the same route the current Comet achieved 15.1 m.p.g. without using the optional overdrive ratio, and 16.65 m.p.g. with this sixth gear in use, the figure over a hilly route being 14.8 m.p.g.

With these performance figures in mind, and taking into account also the very sound design and construction of the present-day Comet, together with the pleasant driving conditions and handling characteristics offered, this 12-tongross design becomes a sound proposition for the operator requiring a 7/8-ton vehicle which will give him long service at low overall cost.

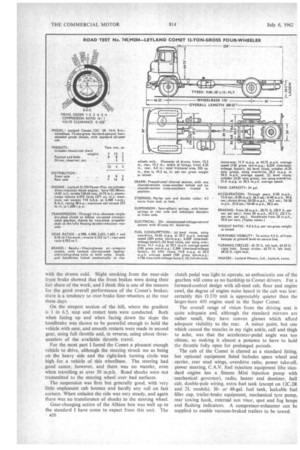

The model tested was the 12C.3R 14-ft. 8-in.-wheelbase Comet, which has a body space of 18 ft. 8 in. In kerb condition, but without spare wheel, the chassis-cab weighed 3 tons 12.75 cwt., the frontand rear-axle figures being 2 tons 7 cwt. and 1 ton 5.57 cwt. respectively. Iron weights, mounted on robust timber runners, brought the kerb weight up to 12 tons 1.25 cwt. (with nobody in the cab), and of

he imposed load the front axle carried 1 ton 18.25 cwt. From these figures it is clear that a short-wheelbase version pf the 12C. Comet could carry an 8-ton payload without xceeding Leyland's 12-ton-gross limit, providing a lightdloy platform body is fitted.

The retardation figures recorded in the accompanying iata panel were obtained without any wheel locking whatioever, and there was no obvious delay in the air-pressure stern, deceleration being impressively smooth and wellmannered. Maximum deceleration rate, as recorded by the Tapley meter, averaged out at 85 per cent, from each speed, which serves to emphasize the small delay and quick pressure build-up of the system. The handbrake performance was equally good, an average Tapley-meter figure of 30 per cent, being obtained from 20 m.p.h. There should be no fear of body movement with -the Comet, despite the outstanding braking performance, because the retardation is so smooth and progressive. This not only reduces body stresses but also cuts down wear and tear on the chassis components, tyres and—not to be scorned—the brakes themselves.

According to the meteorological station at Formby, there was a 44-m.p.h. wind blowing directly down the stretch of road used for the acceleration tests, despite which good acceleration times were obtained through the gears up to 40 m.p.h., the performance up to 30 m.p.h. from a standstill being particularly satisfactory. Direct-drive acceleration between 10 and 40 m.p.h. was not quite so lively, however, .being only marginally better than that obtained in 1954 with the lighter Comet 90. The 12C.'s gears are obviously, there to be used!

• Checks on the speeds obtainable in each of the gears produced the following approximate figures: first, 6 m.p.h.; second, 10 m.p.h.; third, 16 m.p.h.; fourth, 27 m.p.h.; fifth, 43 m.p.h.; and sixth, 56 m.p.h.

The results of the four fuel-consumption tests made while • fully laden are contained in the accompanying data panel, from which it will be seen that the latest Comet by no means has thirsty tendencies. The tests made on a level piece of road with and without overdrive show that this optional sixth gear effects a fuel saving of 9.2 per cent, in the laden condition: subsequent tests made over the same Piece of road with the iron weights removed, but with the timber runners left on the chassis frame to give a total weight of 4 tons 5 cwt., showed that the saving given by the overdrive was some 22.5 per cent, in this simulated unladen condition.

In addition to the direct economies to be gained from use of overdrive, as shown by these level-road tests, the higher top speed effected by the overdrive ratio can in itself result in the use of less fuel, particularly in hilly districts, for the extra 13 m.p.h. or so above that given by direct drive can enable hills to be approached appreciably faster, and so climbed not only more quickly but also in a higher and less fuel-consuming ratio.

The economy of the Comet under hilly conditions is indicated by the third fuel-consumption figure quoted in the panel-14.8 m.p.g. at 26.0 m.p.h. This run was made over a twisty undulating route 10 miles in length; and in view of the conditions the relatively high average speed (which was achieved without exceeding 33 m.p.h.) is as commendable as the recorded consumption rate. Equally satisfactory, of course, is the full-throttle motorway performance, as measured on a 17-mile circuit of the Preston By-pass (M), a stretch of motorway considerably more hilly than the M1 London-Birmingham road.

Parbold Hill, which has an average gradient of 1 in 12 and is 0.75-mile long, was used for the gradient-performance tests, these being conducted in an ambient temperature of 15" C. (59° F.). A fairly fast climb was made in a total time of 3 minutes 55 seconds, and this caused the enginecoolant temperature to rise from its normal value of 710 C. (160' F.) to 790 C. (174° F.)—a quite reasonable rise, indicating that the pressurized cooling system is big enough for operation in this country. The lowest speed observed during the climb was 9 m.p.h., this being during the 56 seconds that second gear was engaged, and there was no visible exhaust smoking at any time.

Good fade-resistance characteristics were shown after descending Parbold Hill in neutral. at 20 m.p.h., the footbrake having been applied for 2 minutes 20 seconds. At the bottom of the hill a Tapley-meter reading of 67 per cent, was obtained from 20 m.p.h., which compares well with the 85 per cent. maximum achieved earlier in the day with the drums cold. Slight smoking from the near-side front brake showed that the front brakes were doing their fair share of the work, and I think this is one of the reasons for the good overall performance of the Comet's brakes: there is a tendency to over-brake four-wheelers at the rear these days.

On the steepest section of the hill, where the gradient is 1 in 6.5, stop and restart tests were conducted. Both when facing up and when facing down the slope the handbrake was shown to be powerful enough to hold the vehicle with ease, and smooth restarts were made in second gear, using full throttle and, in reverse, using about threequarters of the available throttle travel.

For the most part I found the Comet a pleasant enough vehicle to drive, although the steering struck me as being on the heavy side and the right-lock turning circle was high for a vehicle of this wheelbase. The steering had good castor, however, and there was no wander, even when travelling at over 50 m.p.h. Road shocks were not transmitted to the steering wheel over bad surfaces.

The suspension was firm but generally good, with very little unpleasant cab bounce and hardly any roll on fast corners. When unladen the ride was very steady, and again there was no transference of shocks to the steering wheel.

Gear-changing action of the Albion box was well up to the standard I have come to expect from this unit. The 13/0 clutch pedal was light to operate, so enthusiastic use of the gearbox will come as no hardship to Comet drivers. For a forward-control design with all-steel cab, floor and engine cowl, the degree of engine noise heard in the cab was low: certainly this 0.370 unit is appreciably quieter than the larger-bore 400 engine used in the Super Comet.

The overall range of vision from the driving seat is quite adequate and, although the standard mirrors are rather small, they have convex glasses which afford adequate visibility to the rear. A minor point, but one which caused the muscles in my right ankle, calf and thigh to ache, was that the accelerator-pedal angle was too obtuse, so making it almost a penance to have to hold the throttle fully open for prolonged periods.

The cab of the Comet is classed as a standard fitting, but optional equipment listed includes spare wheel and carrier, rear mud wings, overdrive ratio, power take-off, power steering, C.A.V. fuel injection equipment (the standard engine has a Simms Mini injection pump with mechanical governor), radio, heater and demister, half cab, double-pole wiring, extra fuel tank (except on 12C.2R and 2L models), 36or 48-gal. fuel tank, lockable fuel filler cap, trailer-brake equipment, mechanical tyre pump, rear towing hook, external sun visor, spot and fog lamps and flashing indicators. A compressor-exhauster can be supplied to enable vacuum-braked trailers to be towed.