Breakilig i hard to do

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Demand is increasing for trucks to be recycled down to the last nut and bolt. How are the truck manufacturers responding to this new-from-old challenge?

Recycling is one of the basics of the sustainable economy and already the environmentalists are pointing the finger at motor vehicles. From October this year the price of every new car and truck sold in Switzerland has included a 75 Swiss Franc (MO) surcharge which will go towards paying for a number of incineration plants designed solely to handle those parts which cannot be recycled. For once the truck industry is ahead of the game and ready to meet the challenge of the recyclable truck.

Apart from aluminium drinks cans, cars and trucks are already about the most recycled products on the planet. Ever since the Second World War a whole industry has grown up around breaking vehicles, and either selling their parts directly or remanufacuring them for resale. However, modern environmentalists are pressing for even greater efforts by the vehicle industry and in response the manufacturers have begun to get to grips with the problem.

Conventional materials such as cast iron, steel and aluminium are relatively easy to recycle and although high-grade steels used for axle beams or chassis rails are unlikely to be re-used for the same components they could end up in sheet steels or castings. Glass is also easy to recycle although laminated windscreens require some extra processing to remove the plastic laminations.

Reconstituted

Batteries too, are almost totally recyclable; the lead plates, polypropylene cases and even the acid can all be used again to make new batteries. Great strides have been made in recovering a truck's vital fluids and today oils can be cleaned and reconstituted, coolants can be broken down and the chemicals reclaimed and even the liquified gases used in air conditioning systems can be safely collected and reused.

Unfortunately all of these processes take time and cost money. And if recycling is to work in a free market without the threat of overbearing legislation, they have to yield first-class quality materials at the same price or less than the new alternatives To achieve this, the manufacturers must find a way of systematically breaking trucks down in a truly cost efficient way.

Car manufacturers have made a start and new cars are being designed with recyling in mind. Nonetheless Ford reckons that anything that cannot be salvaged within half an hour is not worth the extra cost of the time needed to retrieve it.

Because of its sheer size, the breakeven point on a truck will be longer. According to Scania, a typical R113 4x2 tractor which weighs 5.9 tonnes is made up of some 8,000 individual parts. Scania says 5.1 tonnes of this total (or 87%) is recoverable by today's techniques (see table opposite for detailed breakdown).

Scania doesn't put a cost on breaking the

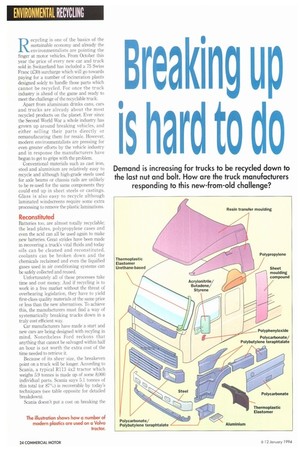

The illustration shows how a number of modern plastics are used on a Volvo tractor.

vehicle but it will be substantial and may not be economic in the short term. There is no gold in a truck although modern car catalysts typically use up to two grammes of equally rare and expensive metals such as platinum, niobium and rhodium which recyclers go to great lengths to recover. The time and effort spent recovering less exotic metals such as copper from a wiring loom is determined by the market price for copper.

In this context something as complicated as a modern truck seat with its electric motors and pump-up panels, steel frame, plastic trim, foam rubber padding and woven upholstery material presents a real challenge, Having spent valuble time breaking the vehicle down there is still the extra, and sizeable cost of transporting the individual materials to the recycler. The economics of the whole process are not clear but it would seem sensible to combine breaking and recyling on a single site.

The Swiss authorities accept that trucks cannot be completely recycled at an economic cost by today's methods and this is the main reason they have introduced the recycling tax and plan to open incineration plants. Some local councils have already imposed dumping bans and from 1996 it will be illegal to dump truck parts anywhere in Switzerland.

With 235,000 light and medium trucks and 54,000 heavy trucks on their roads today, the Swiss have decided to tackle the problem head on. Materials which cannot be economically recycled will be incinerated and the remains presumably buried in landfill sites.

One truck part that is impossible to recycle and difficult to burn cleanly is the tyre. Good carcases can be retreaded and used again but eventually when they reach the end of the road their size and weight makes them difficult to dispose of easily and economically

Energy

However, Britain is ahead of environmentally conscious Switzerland in having Europe's only power station fuelled solely by old tyres. Tyres produce more energy per kilo than coal and when burnt at temperatures of up to 950° Centigrade, release enough energy to produce steam and thus drive a turbine to produce electricity At Elan Energy's plant in Wolverhampton five furnaces produce enough heat to generate 30MW of electricity, sufficient to supply 25,000 homes. So with all the steel, aluminium, copper, glass, tyres and fluids taken care of, what is left?

Some years ago the answer would have been "precious little" but today's trucks use considerable amounts of plastics, some of which are extremely difficult to deal with and up till now have either been incinerated or buried in land-fill sites. Volvo estimates that currently about one million tonnes of plastics from vehicles of all types are buried each year. The industry is aware of the problem and has begun to implement new systems for marking and identifying all

plastics parts with a code. Two such systems are the internationally recognised IS011469 and the German national standard VDA 260.

Volvo, Scania and MAN with its recently introduced L2000 Series, are among those manufacturers aleady using a plastics coding system. Ultimately the universal use of these codes will allow the person responsible for scrapping or reusing the component to know exactly what it is made of and thus exactly how to deal with it. Volvo says that its trucks now use between 150 and 210 kilos of plastics, mainly of the thermoplastic type. Plastics in this group are preferred because they melt down allowing them to be easily and cleanly recycled.

The other broad group, thermosetting plastics, undergo a chemical change in their manufacture and are almost indestructable other than by incineration. Volvo has concentrated on the use of the evironmentally kinder thermoplastics group and modern FH trucks use 97% thermoplastics.

The age of the fully recyclable truck is not yet with us but the move towards it has begun and will gain momentum in the years ahead.

As a result of a Ford-sponsored project at Southampton University, two devices have been developed which can identify plastics waste using the "fingerprint" of individual materials.

Such technology and an awareness by designers of the recycling requirement will mean that trucks will become much easier to scrap . In the next century everything bar the paint, glues and sealants will be recyclable. By then it may even become economic to scrap or "reprocess" a truck long before it becomes inefficient let alone old.

E by Gibb Grace