The peacemakers

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Rcached an impasse? Negotiations in deadlock? All trust in the opposing side evaporated? Does industrial action seem inevitable? Don't despair: you still have a chance to avoid a costly stoppage—call for ACAS.

This is a super hero with a briefcase and the name ACAS is, of course, an alias. The more accurate description is the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service. It is universally praised by employers and unions alike. Like any good super hero, its reputation for impartiality is unquestioned. While it does not court publicity, the occasional interview is granted on the grounds that the more people who know about its existence, the better the chance of providing help where and when it's most needed. Modesty is standard issue, services are free and confidences are never leaked. In fact it's hard to believe that this is, in fact, a government body: "Our statutory duty is to help promote the improvement of industrial relations," says ACAS director of strategy, Peter Syson, perpetuating the image of the do-gooder. "We can only do that if we retain an independent stance so that employers, unions and individ uals can come to us and be assured of our independence and confidentiality."

ACAS achieves its aims through arbitration, mediation and conciliation:

• Arbitration is where a choice is made between different situations put by different sides; • Mediation means arriving at a solution somewhere between the two; • Conciliation is working between the two positions to arrive at a third, hopefully acceptable position.

The adventures of our peace-making hero were last recorded in Commercial Motor news pages only last month. We reported how ACAS swooped to help bust a long-running pay dispute at container carrier Goodways.

Pay and conditions negotiations had dragged on from March to October 1996 with no sign of a deal. Union members had been balloted and voted in favour of industrial action. Discussions continued and there was a further ballot. A date was set for strike action. Then, with the agreement of the company, ACAS was called in.

Eye witness

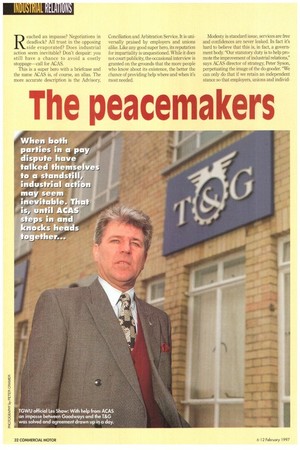

Les Shaw, the Transport & General Workers Union official who is also secretary to Goodways' national negotiating committee, was an eye witness. "Both parties were on neutral ground in separate rooms and ACAS attempted to broker an agreement," he says. "It was reached, drawn up and signed on the same day."

As part of the settlement, the basic pay offer was increased from 1.5% to 3.5%— and both sides were happy that the dispute was resolved without recourse to strike action.

Susan Cordell, administration manager at Goodways, explains: "When you're sitting on one side of the negotiation, with employees on the other, it's very difficult sometimes to see all parts of the argument. ACAS representatives are good and they can often see things that one of the other sides is missing" ACAS's reputation for restoring trust among workers and management was developed through 11th-hour settlements of highprofile industrial disputes during the 1970s and 1980s. Railwaymen, London Transport bus drivers, Merseyside dockers and more recently postal workers have all seen deadlocked wheels begin to turn following the arrival of the man from ACAS However, in the late 1980s the need for our hero's services began to wane a little. Chris Brewster is professor of European resource management and also the director for strategic trade union management at Cranfield University School of Management. He believes that this was not beause people stopped believing in ACAS; just that stronger forces were at work.

"Perhaps people felt there were no industrial relations problems any more," he says. "Maggie Thatcher had seen to all that. As a result, some industrial relations responsibility was pushed down through the organisation and out to the line managers. It has since been realised that you are just as likely to have an industrial relations problem in those circumstances, if not more likely to have them."

The ACAS record of success has not gone unnoticed by the political parties, and opportunities to extend its role in strike prevention are regularly kicked around the corridors of Parliament.

Last November, for example, the Government published a green paper on strike prevention in the essential services. But although the importance of conciliation was considered, it was decided that compulsory referral to a conciliation body would not be an appropriate step.

The Labour Party also says that it has no policy to make the arbitration process corn

pulsory, but adds that it is currently consulting on ways to improve industrial relations in the public sector.

According to David Blunkett MP, shadow Education and Employment Secretary, Labour's aim is "to find the most effective ways of preventing disputes from taking place and of resolving them before industrial action takes place when they do happen. That is why we announced in September our plans to consult on proposals for more effective arbitration and conciliation to help prevent disputes."

Compulsion

The problem with imposing the conciliation process by law is that compulsion will hardly engender those essential elements of trust and impartiality. At the moment, services from ACAS are totally free. The argument for this is that if somebody had to pay, it would inevitably end up being the employer, and that too would be seen as compromising impartiality.

However, there are other issues. Val Pugh, national officer with special responsibility for transport at the Union of Shop Distribution and Allied Workers, says that in the current economic climate few employers would relish being forced into arbitration.

Chris Brewster explains, by way of this hypothetical scenario, how arbitration is not always a preferred option: "ACAS might say 'we hear the union asking for 10%, the management is offering 2% and we think the fair answer should be 8%.' If I were a manager, or indeed a union representative—because the result could equally go the other way—I'm not sure I would want to abrogate my responsibilities so far that I let someone else decide either my wage bill, or my members' living standards."

The ACAS superhero of the 1990's wears a slightly different costume to the one required during the major deal-brokering days of the 1970s and 1980s. Nowadays most of ACAS's work involves conciliation services to individuals who contact the organisation through one of 11 operational sites around the UK. They are often people seeking redress from past and present employers; perhaps for unfair dismissal, unfair deduction of wages or even sex discrimination.

Any case destined for an industrial tribunal is automatically referred to ACAS. The service to the individual is just as free and the conciliation settlement rate is just as impressive.

The man from ACAS can proudly boast that only 30% of the individual caseload ever reaches the tribunal stage. What a super guy! 0 by Steve McQueen