HYDRALIC TRANS /USSR" REDUCES ( HAS SIS WEAR

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

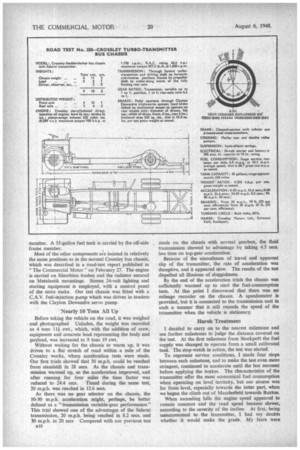

Salerni Transmitter Promotes Smooth Riding, Saves Wear on Bodywork and Chassis Components, Gives a High Rate of Acceleration, but Slightly Increases Fuel Consumption

By L. J. COTTON, m.t.R.T.E.

SIMPLICITY of control and smoothness of acceleration are two prominent features in the operation of the Crossley bus equipped with the Salerni transmitter. The "variable gearing" afforded by the transmission dispenses with the need for a normal gearbox, so that the driver can devote more attenZion, and both hands, to steering the vehicle.

Unlike the orthodox forms of transmission, there is no clutch or gearbox, and the system cannot be abused by bad driving. This, whilst affording a more comfortable journey for the passengers, also has its advantages in prolonging the ultimate life of the propeller-shaft couplings, differential and drive of the rear axle, and reducing wear on tyres.

Except for the bearings, there are no metallic parts in contact in the Salerni transmitter All the moving parts operate under ideal conditions, being immersed in engine oil, which is employed as the transmission fluid. It may be necessary to replace an oil seal, at widely spaced intervals, but other than that there is little in the system which might call for attention or renewal.

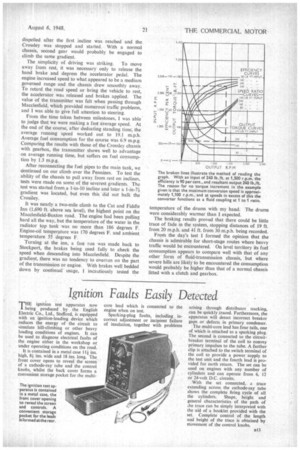

Construction of the Transmitter Basically, the unit, made by Brockhouse Engineering (Southport), Ltd., comprises, two turbine, or driven, elements and reaction members. The reaction assembly, located at the centre of the unit, is mounted on a free wheel; thus it is able to rotate freely when not in operation, that is, when the torque ratio is 1 to 1. It is in operation only when performing its normal function of deflecting the oil during transmission at low ratios.

An advantage of the design is that the vaned elements are plain die castings or stampings and, other than drilling and turning, there ig practically no machining required. There are no inserts in its construction which might work loose in operation It might be expected that high oil temperatures might be developed. Experiments have been made to check the temperature under normal working conditions, a thermometer being interposed in the fluid Under normal loadings the oil was approximately 120 degrees B8 C., and rose to 180 degrees C. under extreme conditions of load and gradients.

Oil at this temperature is not allowed to contact the atmosphere, because the transmitter is a closed-circuit system and is supplied from an external header tank. As there is no circulation of oil in the header tank, the reserve fluid is retained at approximately ambient temperature.

To obtain the best performance from the Salerni transmitter, it is essential that a reasonably largecapacity engine be employed, affording a high power-toweight ratio. In the bus chassis it is driven by the Crossley 8.6-litre direct-injection oil engine, which develops 100 n.h.p. at its governed speed of 1,750 r.p.rn The maximum torque of the engine is 377.5 lb.-ft. at 1,000 r.p.m.

Gear Changes with Engine Idling The casing of the transmitter is secured to the engine banjo and its rotating element bolted direct to the crankshaft flange. A cardan shaft, equipped with Hardy Spicer universal couplings, connects the unit to a forward-and-reverse gearbox. Changes from forward to reverse, or vice versa, are made with the engine idling, a heel pedal being provided which is linked to a rocking brake to overcome the torque, drag. To prevent misuse, should the driver treat the pedal as a footrest, it is interconnected with the hand brake, so that it may be depressed only when the hand brake is applied. The gearbox is linked to a normal-positioned lever in the cab The epicyclic forward-and-reverse gear train is solid when driving ahead, thus silencing the transmission line.

The output shaft of the gearbox drives through a standard propeller shaft to the underslung worm drive of the rear axle. A standard fully floating axle is employed with a final-drive ratio of 6 to 1. A Clayton Dewandre triple-servo braking system is fitted, the main servo motor being located inside the frame, whilst the vacuum tank is positioned outside the near-side frame member. A 35-gallon fuel tank is carried by the off-side frame member.

Most of the other components are located in relatively the same positions as in the normal Crossley bus chassis, which was described in a road-test report published in "The Commercial Motor on February 27. The engine is carried on Silentbloc bushes and the radiator secured on Metalastik mountings. Simms 24-volt lighting and starting equipment is employed, with a control panel of the same make. Our test chassis was fitted with a C.A.V. fuel-injection pump which was driven in tandem with the Clayton Dewandre servo pump.

Nearly 10 Tons All Up

Before taking the vehicle on the road, it was weighed and photographed Unladen, the weight was recorded as 4 tons 11i cwt., which, with the addition of crew, equipment and concrete load representing the body and payload, was increased to 9 tons 19 cwt.

Without waiting for the chassis to warm up, it was driven to a flat stretch of road within a mile of the Crossley works, where acceleration tests were made. Our first trials showed that 30 m.p.h. could be reached from standstill in 28 secs. As the chassis and transmission warmed up, so the acceleration improved, and after running for four miles the time factor was reduced to 24.4 secs. Timed during the same test, 20 m.p.h. was reached in 12.6 secs.

As there was no gear selector on the chassis, the 10-30 m.p.h. acceleration might, perhaps, be better defined as a "transmission variable-gear performance." This trial showed one of the advantages of the Salerni transmission, 20 m.p.h. being reached in 8.2 secs. and 30 m.p.h. in 20 secs Compared with our previous test e10

made on the chassis with normal gearbox, the fluid transmission showed to advantage by taking 4.5 secs. less time on top-gear acceleration.

Because of the smoothness of travel and apparent slip of the transmitter, the rate of acceleration was deceptive, and it appeared slow. The results of the test dispelled all illusions of sluggishness.

By the end of the acceleration trials the chassis was sufficiently warmed up to start the fuel-consumption tests. At this point I discovered that there was no mileage recorder on the chassis. A speedometer is provided, but it is connected to the transmission unit in such a manner that it still records the speed of the transmitter when the vehicle is stationary.

Harsh Treatment 1 decided to carry on to the nearest milestone and use further milestones to judge the distance covered on the test. At the first milestone from Stockport the fuel supply was changed to operate from a small calibrated tank. The stop-watch in action, the test was started.

To represent service conditions, I made four stops between each milestone, and to make the test even more stringent, continued to accelerate until the last moment before applying the brakes. The characteristics of the transmitter offer the most economical fuel consumption when operating on level territory, but our course was far from level, especially towards the latter part, when we began the climb out of Macclesfield towards Buxton.

When ascending hills the engine speed appeared to remain constant and the road speed became slower, according to the severity of the incline. At first, being unaccustomed to the transmitter, I had my doubts whether it would make the grade. My fears were

dispelled after the first incline was reached and the Crossley was stopped and started. With a normal chassis, second gear would probably be engaged to climb the same gradient.

The simplicity of driving was striking. To move away from rest, it was necessary only to release the hand brake and depress the accelerator pedal. The engine increased speed to what appeared to be a medium governed range and the chassis drew smoothly away. To retard the road speed or bring the vehicle to rest, the accelerator was released and brakes applied. The value of the transmitter was felt when passing through Macclesfield, which provided numerous traffic problems, and I was able to give full attention to steering.

From the time taken between milestones, I was able to judge that we were making a fast average speed. At the end of the course, after deducting standing time; the average running speed worked out to 19.1 m.p.h. Average fuel consumption for the course was 6.9 m.p.g. Comparing the results with those of the Crossley chassis with gearbox, the transmitter shows well to advantage on average running time, but suffers on fuel consumption by 1.3 m.p.g.

After reconnecting the fuel pipes to the main tank, we continued on our climb over the Pennines. To test the ability of the chassis to pull away from rest on inclines. tests were made on some of the severest gradients. The test was started from a 1-in-10 incline and later a l-in-71 gradient was located, but even this 'did not balk the Crossley.

It was nearly a two-mile climb to the Cat and Fiddle Inn (1,690 ft. above sea level), the highest point on the Macclesfield-Buxton road. The engine had been pulling hard all the way, but the temperature of the water in the radiator top tank was no more than 186 degrees F. Engine-oil temperature was 170 degrees F. and ambient temperature 55 degrees F.

Turning at the inn, a fast run was made back to Stockport, the brakes being used fully to check the speed when descending into Macclesfield. Despite the gradient, there was no tendency to overrun on the part of the transmission or engine. With brakes well bedded down by continual usage, I incautiously tested the temperature of the drums with my hand. The drums were considerably warmer than I expected.

The braking results proved that there could be little trace of fade in the system, stopping distances of 19 ft_

from 20 m.p.h. and 41 ft. from 30 m.p.h. being recorded. From the day's test 1 formed the opinion that the

chassis is admirable for short-stage routes where heavy traffic would be encountered. On level territory its fuel consumption appears to compare well with that of any other form of fluid-transmission chassis, but where severe hills are likely to be encountered the consumption would probably be higher than that of a normal chassis fitted with a clutch and gearbox.