MORE POWER PE CAB SPACE

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

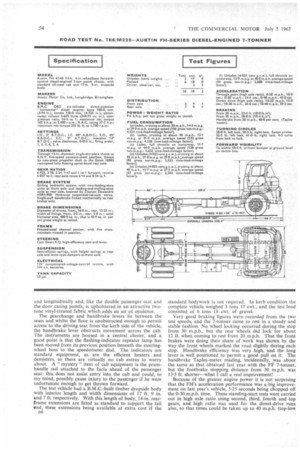

ONE of the principal handicaps to driving comfort in any conventional forward-control cab is the intrusion made into the cab by the engine compartment. It causes the interior to be cramped and raises problems of noise and heat. A fairly satisfactory way of overcoming these objections, whilst retaining a straightforward chassis layout is to turn the engine on to its side and house it beneath the cab floor, which is the solution employed in the B.M.C. FH-series 5-, 7and 8-ton diesel-engined chassis, which are marketed under the brand names of Austin and Morris but which otherwise are identical. A full description of the range appeared in the March 22 issue of The Commercial Motor.

A road test of a 7-ton FH vehicle showed that this reasonably simple expedient has made the FF-series cab into a quiet and comfortable driving compartment with ample room for at least two people to sit alongside the driver, the engine being installed at an angle of 29° to the horizontal. Admittedly, engine accessibility has suffered in the process, whilst the means of getting into and out of the cab are unaltered. But the transformation is quite remarkable in other respects, and its revised cab makes the latest B.M,C. 7-tonner a most pleasant vehicle to drive.

Another significant result of this test is that the fuel economy with the 5-7-litre diesel is substantially better than that with the 5.1-litre engine which was fitted to the FFcabbed 7-tonner tested last year, whilst the tests showed the extra engine power to give—as might be expected—marked improvements in respect of acceleration and hill-climbing performances. This 5-7-litre unit is standard in the Fli 7-tonner, although it is still optional in the FF models, and it is a particularly good enlarged-bore derivation of an engine which has already proved its worth over a number of years. The additional torque output is of great value, and endows this new 7-tonner with a lively and laboursaving top-gear performance.

The " horizontal " 5-1and 5-7-litre engines are virtually identical with the upright versions, differing mainly in respect of sump layout, and the two units themselves have numerous common components. Because of the semihorizontal engine location, chassis in the FH range lend themselves to passenger applications and the long-wheelbase versions are actually offered for such use, bodies with up to 45 seats being mountable on the 17-ft. 6-in-wheelbase 7-tonner, which can run at 11 tons gross weight with suitable tyre equipment.

The FH K140 has an E.N.V.-designed five-speed gearbox as standard, this being available with overdrive or direct top gears and having p.t.-o. faces on each side. The standard axle is a single-speed spiral-bevel unit with ratios of 5-86 or 6-67 to 1, whilst available at extra cost (£168 5s.) is a series of Eaton two-speed axles. With the direct-top box and the 5-86-to-1 axle the 7-tonner on 9-00-20 tyres will have a maximum speed of about 55 m.p.h. and a gradient ability approaching 1 in 4-5, so this seems a very logical gearing combination for general haulage duties. The overdrive box with the same axle would raise the speed by about 10 m.p.h., but reduce the gradient ability to 1 in 5. The vehicle tested had the 6-14/8-54-to-1 Eaton 16802 axle, giving a maximum speed of just over 50 m.p.h. and a gradient ability of nearly 1 in 3. Except for the additional gradient ability, it is not likely that this Eaton axle gives a greatly improved road performance when compared with the standard single-speed axle, so 1 do not feel that the extra expense is really justified in this case. Of course, if really high top speed is required whilst retaining good gradient performance, the 4-89/6.8-to-1 axle would be an obvious choice as this would give, with the direct-top box, a gradient ability better than 1 in 4 and a top speed of well over 60 m.p.h. If the overdrive box were used with this axle, the speed would go up into the 70s and the gradient ability would still be better than 1 in 5.

Other Eaton ratios are also available, and it would be wise for the potential purchaser of this model to go very carefully into all the available sets of ratios so that he can be sure of getting the most suitable combination for his particular operations.

An innovation is that the rear-mounted spare-wheel carrier incorporates wooden rollers to facilitate movement of the wheel.

Good suspension, both laden and unladen, is a commend able feature of this FH chassis. The front springs are 2-25 in. wide and 45 in. long and lever-type dampers are standard. On all but the 10-ft.-wheelbase model, which has 51-in.-Iong springs, the rear springs are 60 in. long and 2-5 in. wide, with 35-in.-long helper springs as standard. Lever dampers are optional.

The standard chassis has unassisted Cam Gears high-efficiency cam and lever steering gear, but servo equipment is offered at extra cost. Unless severe overloading is contemplated, t hi s servo should not be necessary, the steering of the test vehicle having been firm without heaviness-even at low speeds— and the castor being helpful but not fierce. Just over four and a quarter turns of the wheel are required from lock to lock, and as slightly higher ratio gear is fitted when the servo is specified, this would reduce the number of turns to about four.

Although, nominally, the braking system of the FH 7-tonner tested is the same as that of the FF 7-ton tipper tested last year, obviously work has been done on the brakes, for when the drums were cold the retardation efficiency was much better. Fade resistance, however, was much worse, which suggests that a lining-specification change would not come amiss. An Air Pak air-pressure servo is offered, and this might do something to alleviate the fade condition if only by reducing pedal effort.

On the standard 8-25-20 (12-ply) tyres this 7-ton chassis

rated for a gross weight of 10,25 tons, which means that a genuine payload of 7 tons cannot be carried. An 11-ton rating applies, however, When either 8.25-20 (14-ply) or 9-00-20 (12-ply) equipment is fitted.

As stated, the cab has the same basic shell as the earlier FF models. However, the driving comfort given by the FH cab is well up to the currently accepted standard for vehicles of this price and class, even though the raked rear panel still means that the driver can bang his head if he leans well back. As an indication of B.M.C.'s desire to provide good driving conditions, even windscreen washers are fitted as standard (though the wiper sweep pattern is bad), whilst the electrical switches have been conveniently grouped in a panel to the right of the steering column (on the left of the column, of course, on left-hand-drive

• versions). The separate driving seat is adjustable vertically co

and longitudinally and, like the double passenger seat and the door casing panels, is upholstered in an attractive twotone vinyl-treated fabric which adds an air of opulence.

The gearchange and handbrake 'levers lie between the seats and whilst the floor is unobstructed enough to permit access to the driving seat from the kerb side of the vehicle, the handbrake lever obstructs movement across the cab. 'Fhe instruments are housed in a central cluster, and a good point is that the flashing-indicator repeater lamp has been moved from its previous position beneath the steeringwheel boss to the speedometer dial. The indicators are standard equipment, as are the efficient heaters and demisters, so there are virtually no cab extras to worry about. A " mystery " item of cab equipment is the pramhandle rail attached to the facia ahead of the passenger seat: this does not assist entry into the cab and could, to my mind, possibly cause injury to the passenger if he were unfortunate enough to get thrown forward.

The test vehicle had a B.M.C.-built timber dropside body with interior length and width dimensions of 17 ft. 9 in, and 7 ft. respectively. With this length of body, 14-in, rearframe extensions are fitted as standard to support the tail end, these extensions being available at extra cost if the D6

standard bodywork is not required. In kerb condition the complete vehicle weighed 3 tons 17 cwt., and the test load consisted of 6 tons 18 cwt. of gravel.

Very good braking figures were recorded from the two leg_ speeds, and the 7-tonner came to rest in a steady and stable fashion. No wheel locking occurred during the stop from 30 m.p.h., but the rear wheels did lock for about 12 ft. when coming to rest from 20 m.p.h. That the front brakes were doing their share of work was shown by the way the front wheels marked the road slightly during each stop. Handbrake efficiency was very high, and the long lever is well positioned to permit a good pull on it. The handbrake Tapley-meter reading, incidentally, was about the same as that obtained last year with the FF 7-tonner, but the foothrake stopping distance from 30 m.p.h. was 13-5 ft, shorter—what I call a real improvement!

Because of the.greater engine power it is not surprising that the Fin acceleration performance was a big improvement on last year's vehicle, 5-25 seconds being chopped off the 0-30 m.p.h. time. These standing-start tests were carried out in high axle ratio using second, third, fourth and top gears, and high ratio was used for the direct-drive runs also, so that times could be taken up to 40 m.p.h. (top-low

is good for only 38 m.p.h.). Better times between 10 and 30 m.p.h. would undoubtedly have been obtained had the low ratio been used, but even so the figures recorded are good and emphasize the very useful top-gear performance given by the 5.7-litre engine.

The three laden fuel-consumption figures show only average economy, but even so they are better than those recorded last year with the FF, the same stretch of road being used for the normal runs and the only test-condition difference being that the FE was grossing 3-5 cwt. more. Whereas the 1962 vehicle achieved only 13-2 m.p.g. at 27.7 m.p.h. average speed, under identical conditions the FH returned 14.3 m.p.g., whilst the extra engine power enabled the average speed to be raised by 1.3 m.p.h.

Enthusiastic use of the throttle plays havoc with the consumption rate, but reasonable driving on normal British roads at the recommended gross weight should not result in the fuel figure being much heavier than 14 m.p.g. on average, whilst, as the unladen results show, empty running with the same style of driving should result in reasonable overall fuel economy.

Gradient-performance tests were carried out on Fish Hill, Broadway. This climb is 1.25-mile long and has an average severity of 1 in 14-2, so it is not a stretch of road to be taken lightly. The tests were carried out in an ambient temperature of 16°C. (61°F.), and there was no wind to speak of. Recording the engine-coolant temperature presented a problem with this design, for the radiator is a wide, shallow assembly which is filled through a tube which is something like 18 in. tong, making it impossible to take direct readings of the header-tank temperature with a conventional stick thermometer. However, before making the climb the temperature at the top of the filler tube was recorded as 66°C. (151°F.).

The ascent took 5 min. 45 sec. which is a clear minute shorter than the time taken with the FF tipper last year, and the lowest ratio-combination used was third-low, this being engaged for 4 min. 30 sec., during which time the speed never fell below 15 m.p.h. The swiftness of the climb again emphasizes the advantage of having an engine of this size in a vehicle of this weight. Because of water-loss due to expansion when the cap was removed, the coolant temperature rise could not be recorded. It was impossible for the same reason, to tell whether the capacity of the system was sufficient, and one can only assume that the B.M.C. development department is satisfied.

The emission of smoke was a bit disappointing, and it was not confined to this one particular hill climb: even on normal roads the exhaust was still smoky—though not to any dangerous degree—and checking all the injectors thoroughly did not provide a cure. I am left to assume, therefore, that the fuel-pump settings were at fault, because it is hardly likely that this 5.7-litre engine would have been designed to produce its maximum power with a smoky exhaust.

Fade-resistance was tested by coasting the 7-tanner down Fish Hill in neutral and using the footbrake to keep the speed down to 20 m.p.h. This test lasted 4.25 minutes, and even by the time I was half-way down the hill I found I was having to apply a pretty high effort on to the brake pedal to keep the speed down: at the bottom of the hill it was almost unnecessary to simulate "panic stop" conditions, because I was getting extremely worried as to whether there were any brakes left at all.

By giving the pedal everything I'd got I managed to get a Tapley-meter reading of 17 per cent, indicating that the efficiency had dropped by 0-57g as a result of this- admittedly severe—test. All the brakes were smoking profusely, and the pedal travel had increased to such an extent that there was no more pedal left. The amount of fade recorded needs attention. It spoils what is otherwise a very good braking system, for the brakes are such that under normal driving conditions the amount of feel is good arid the vehicle is easy to control, even though for normal retardations the pedal effort required tends to be high.

Stop and restart tests were carried out on the steepest section of Fish Hill, where the gradient is 1 in 10.5, but this was obviously not severe enough to give the engine a chance to show its paces as get-aways were possible in thirdlow—the same ratio in which most of the non-stop climb was made. Accordingly, I used a 1-in-7 stretch of road inside the Longbridge Works and the handbrake held the 7-tanner quite easily on this slope, both facing up and down the gradient, whilst smooth part-throttle restarts were made in second-low and reverse-high respectively, indicating ample engine power.

Drivers will enjoy handling this FH model, once they have got into the cab. The liveliness of the engine is obvious from the comments I have already made, whilst the noise it emits is, for the most part, successfully disguised by the unit's location beneath the floor and the soundinsulating material lying on the floor. The gearbox is a very pleasant one to use, and the lever is well positioned. The steering is completely satisfactory, as is the suspension itself. The only trouble in this connection is that, from the viewpoint of an occupant of the passenger seat, the cushion is far too lively (a spring-case assembly) with the result that the benefits of the chassis suspension are lost.

Where the cab design does fall down is in respect of engine accessibility. The two central floor plates are removable, and to get at them it is only necessary to roll back the one-piece rubber matting. This done, however, one is then confronted with 10 bolts to remove and, even with the plates taken up, access is given only to the injection pump, lift pump, exhauster, generator, fan belt, fuel filter and the first four injectors. B.M.C. realize that the accessibility to the rest of the engine is not all that brilliant, because, they go so far as to suggest that the near-side front wheel should be taken off to enhance accessibility.

By way of compensation, there is a small hinged trap in the floor which gives access to the dipstick and oil filter. The maintenance of the rest of the chassis follows conventional lines, except that the oil-bath air cleaner, is behind the cab, below frame level, therefore a trap is required in the body floor to give access to it.

In chassis-cab form the FH I(140 model as tested has a list price of £1,359, and this price on the face of it compares unfavourably with the figure of £1,185 quoted for the equivalent basic chassis-cab FF model. However, when all the items of equipment on the FF which are listed at extra cost and which are standard on the FH are taken into consideration, the equivalent FF's price comes out at £1,300, therefore there is only a price difference of £59.