Overloading the control aspect

Page 61

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Plating and Braking Regulations will compel all transport managers to pay close attention to vehicle loading. It will not do to blame drivers or customers for loading faults. Robert Harrison, Fellow of the Graduate Centre for Management Studies, Birmingham, conducted a research project for the Ministry of Transport into the costs of the 1968 Braking and Plating Regulations. His hitherto unpublished report forms the basis of the second of four special articles.

IT would be paradoxical if the Quantity Licensing Section of the Transport Bill aggravates the overloading problem. Much of the proposed legislation is designed to promote safer commercial transport operations. Yet many observers believe that certain operators now using 18or 20-ton vehicles might purchase two-axle 16-tanners in order to operate freely. The problem is likely to increase here because this class of vehicle is shown to have problems in meeting weight limits. Additionally, there will be the natural temptation on the part of the operator to maintain old payload figures, a temptation that will be acute if the climate for rate increases continues to be frosty.

Fifteen per cent of the companies whose vehicles were weighed in the Metropolitan Weighing Sample were interviewed in connection with the Braking and Plating research. The sample was controlled and contained companies varying from one-man operators to member companies of the Transport Holding Co.

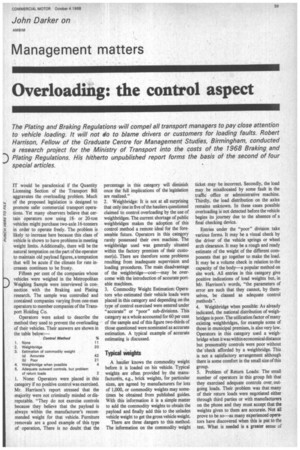

Operators were asked to describe the method they used to prevent the overloading of their vehicles. Their answers are shown in the table below:—

. Control Method 1 None 11

2. Weighbridge 20 3. Estimation of commodity weight

(a) Accurate 42

(h) Poor 21 4. Weighbridge when possible 4 5. Adequate outward controls, but problem of return loads 2

1. None: Operators were placed in this category if no positive control was exercised. Mr. Harrison's report stressed that the majority were not criminally minded or disreputable. "They do not exercise controls because they believe that the payload is always within the manufacturer's recommended weight for that vehicle. Furniture removals are a good example of this type of operation, There is no doubt that the percentage in this category will diminish once the full implications of the legislation are realized."

2. Weighbridge: It is not at all surprising that only one in five of the hauliers questioned claimed to control overloading by the use of weighbridges. The current shortage of public weighbridges makes the adoption of this control method a remote ideal for the foreseeable future. Operators in this category rarely possessed their own machine. The weighbridge used was generally situated within the factory premises of their customer(s). There are therefore some problems resulting from inadequate supervision and loading procedures. The main disadvantage of the weighbridge—cost—may be overcome with the introduction of accurate portable machines.

3. Commodity Weight Estimation: Operators who estimated their vehicle loads were placed in this category and depending on the type of control exercised were entered under "accurate" or "poor" sub-divisions. This category as a whole accounted for 60 per cent of the sample and of this figure two-thirds of those questioned were nominated as accurate estimation. A typical example of accurate estimating is discussed.

Typical Weights

A haulier knows the commodity weight before it is loaded on his vehicle. Typical weights are often provided by the manufacturers, e.g., brick weights, for particular sizes, are agreed by manufacturers for lots of 1.000, or commodity weights may sometimes be obtained from published guides. With this information it is a simple matter to add the commodity weights to obtain the payload and finally add this to the unladen vehicle weight to get the gross vehicle weight.

There are three dangers to this method. The information on the commodity weight ticket may be incorrect. Secondly, the load may be misallocated by some fault in the traffic office or administrative machine. Thirdly, the load distribution on the axles remains unknown. In these cases possible overloading is not detected before the vehicle begins its journey due to the absence of a final checking device.

Entries under the "poor" division take various forms. It may be a visual check by the driver of the vehicle springs or wheel arch clearance. It may be a rough and ready estimate of the weight of the different components that go together to make the load. It may be a volume check in relation to the capacity of the body—a popular method on site work. All entries in this category give positive indications of load weights but, in Mr. Harrison's words, "the parameters of error are such that they cannot, by themselves, be classed as adequate control methods-.

4. Weighbridge when possible: As already indicated, the national distribution of weighbridges is poor. The utilization factor of many existing weighbridges, for example some of those in municipal premises, is also very low. Operators in this category used a weighbridge when it was within economical distance but presumably controls were poor without the check afforded by a weighbridge. This is not a satisfactory arrangement although there is some comfort in the small size of this group.

5. Problem of Return Loads: The small number of operators in this group felt that they exercised adequate controls over, outgoing loads. Their problem was that many of their return loads were negotiated either through third parties or with manufacturers on the phone and they must accept that the weights given to them are accurate. Not all prove to be so—as many experienced operators have discovered when this is put to the test. What is needed is a greater sense of responsibility by all parties in the operation. The Plating Regulations may ensure that this is the only adequate solution.

Responsibility for the effectiveness of controls Controls in themselves are no guarantee of effective prevention of overloading. They are administered, efficiently or poorly, by individuals. Twenty-one per cent of the operators said that the driver was responsible. Mr. Harrison comments: "He is obviously an important factor in the control of overloading, but he cannot seriously be expected to bear the sole responsibility. It is unsatisfactory to allow the driver to be the judge of whether his vehicle is legally loaded. This goes for the 1967 legislation, let alone the Plating Regulations."

Of those questioned 63 per cent referred to management responsibility. Managerial responsibility is self-explanatory and satisfactory if the control purported to be exercised is a genuine control. Unfortunately it was often given where no adequate controls existed in the firm. What in effect these firms were stating was that the management took the responsibility if they were prosecuted and paid all financial penalties.

Overloading has been difficult to detect and prosecutions even harder to obtain. Too often operators have not worried about supervision and controls because the chance of being stopped and checked has been remote. They have been quite willing to pay the small fine if they were caught and prosecuted, accepting this hazard as a normal business risk. In the future a weighing check will be rapid and effective. Overloading carries with it a substantial fine and once the enforcement gets under way companies will be forced to treat it with the seriousness it deserves.

Enforcement policy Operators were asked what form the plating enforcement effort adopted by the Ministry should take for maximum effectiveness. This was, of course, a "loaded" question, but, despite this, most operators made constructive comments. They realized that the Ministry is not going to allow the regulations to become "merely words that everyone promptly ignores"--to quote a small operator.

Random spot checks dominated the replies from operators, though some reservations were expressed. In their present form they can be avoided by the worst offenders, especially if these are operating regularly within the selected area. Greater mobility in site selection was considered desirable. Twelve per cent of the operators believed that the MoT teams should select more sites that illegal operators are known to use. Civil engineering projects are one of the main attractions for illegal operations, yet operators claim that the Ministry never tackles this problem at source.

Mr. Harrison suggests that random spot checks are effective when they can be used by the Ministry but there are three severe limitations: I. They are only carried out in daylight hours while road haulage works 24 hours a day.

2. They are only carried out in good weather, notably in spring and summer. Road haulage works 364 days a year.

3. Road haulage operators know about (1) and (2). What is really needed is an enforcement policy that is not limited to daytime use, which is available all year round and can be respected by the industry. The weighing examination showed that the road haulage industry was not in a strong position to meet the Plating Regulations. The rate of change to a position of strength is entirely proportional to the Ministry's enforcement effort.

Conclusion It may be some comfort to the industry to know that the risk of prosecution for overloading is still a relatively small one. One area examiner I know has told me privately that he does not expect enforcement to be very stringent for two or three years "because there are so many hauliers to whom the Braking and Plating Regulations are a mystery".

Ignorance of the law, we are often told, is no defence. It may well be that the Ministry of Transport, despite the report submitted by Mr. Harrison several months ago, realizes that too stringent application of the law would be harmful to the economy of the country. What annoys road hauliers more than anything is the suspicion that some of their colleagues may prosper while running the relatively small risk of detection. Obviously, if the force of examiners were sufficient to operate random checks, especially in obvious high-risk areas for 24 hours a day, the whole industry could be compelled to comply with the strict requirements of legislation.

M1111■111111