Solving the Problems of the Carrier

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN the issue of The Commercial Motor dated September 13, I set out a scale of minimum rates for beet haulage. The figures shown were carefully calculated on the basis of accurate first-hand knowledge of the conditions under which the work is carried on, with due regard to all the factors .concerned. My object was to give hauliers a lead, to set before them, not merely a minimum scale of charges below which they should, in my opinion, flatly refuse to go, but also to present them with arguments which they could use to back up their own, in their meetings with representatives of the National Farmers Union and of the sugar beet factories.

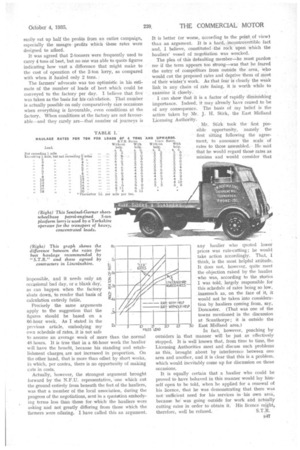

So far as one of the beet-growing areas is concerned, the information appeared too late by one day to be of any service. Hauliers in Lincolnshire, through tht.ir local association, had, on the previous evening, coihe to an agreement with the Farmers Union to carry beet to the local factories at Brigg, Kelharn and Bardney, at a lower scale of rates. The agreed charges are set out in the accompanying table, side by side with the figures that I myself recommended. Fig. 1 shows diagrammatically how the two scales compare.

These Lincolnshire rates are below the , minimum necessary to earn a reasonable profit. In most cases they will not clear the hauliers' costs. They may allow the haulier a meagre profit, but only if conditions be entirely favourable throughoNt the season.

Now, I found, while I was at Scunthorpe, that some of the principal hauliers in the district were dissatisfied with these rates. What is more serious, several of them had already entered into contracts with their customers at much higher rates. They will naturally have to revise these contracts, in accordance with the agreed scale, for, whilst that scale is supposed to be a minimum, it will naturally have been circulated by the N.F.U. to its members and it is not to be imagined that any .farmer will easily be persuaded to pay more than the minimum. These hauliers will thus have to suffer the equivalent of a serious loss, and one which ought never to have occurred. One operator in particular B46 showed me his contracts and gave figures to enable me to satisfy myself that the difference in his revenue for the forthcoming campaign would amount to several hundreds of pounds.

Why, in the face of these facts, were the rates quoted agreed? Why did not the local association insist on being paid reasonable charges? It should be borne in mind that, to a large extent, the matter is in the operators' hands; they have the vehicles, the beet is waiting to be carted, the factories require that beet and there is, to all intents and purposes, no way of transporting it to the factories other than by road. Indeed, it is a matter of history that, some years ago, the factory at Brigg admitted itself to be dependent upon road haulage and actually sought the aid of local hauliers in order to ensure collection of the year's crop.

The principal reason for acceptance, I found, was that the N.F.U. brought to the meeting a transport expert who produced figures in support of the farmers' claim for reduced rates. The hauliers had no one sufficiently expert in the knowledge of operating costs to be able to deal with the arguments brought forward.

So far as I was able to gather in general conversation —I could not obtain exact information—the rates are, broadly speaking, based on a 2-ton lorry as the typical vehicle, carrying 4 tons of sugar-beet. The figures for operating cost were those set out in The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs, ignoring the fact that they apply with any exactitude to a 2-ton lorry only when it is carrying .2 tons, and not when it is 100per-cent. overloaded The incalculable extra cost of this overloading was not taken into consideration at all. It was not, so far as I could ascertain, represented to the farmers that a comparatively minor breakdown, or a burst tyre, either of which was likely to result from this ill-usage, could

easily eat up half the profits from an entire campa.ign, especially the meagre profits which these rates were designed to afford.

It was agreed that 2-tonners were frequently used to carry 4 tons of beet, but no one was able to quote figures indicating how vast a difference that might make to the cost of operation of the 2-ton lorry, as compared with when it hauled only 2 tons.

The farmers' advocate was too optimistic in his estimate of the number of loads of beet which could be conveyed to the factory per day. I. believe that five was taken as the basis for his calculation. That number is actually possible on only comparatively rare occasions when everything is favourable, even conditions at the factory. When conditions at the factory are not favourable—and they rarely are—that' number of journeys is impossible, and it needs only an occasional bad day, or a blank day, as can happen when the factory shuts down, to render that basis of calculation entirely futile.

Precisely the same arguments apply to the suggestion that the figures should be based on a

66-hour week. As I stated in the previous article, embodying my own schedule of rates, it is not safe to assume an average week of more than the normal 48 hours. It is true that in a 66-hour week the haulier will have the benefit, because his standing and establishment charges, are not increased in proportion. On the other hand, that is more than offset by short weeks, in which, per contra, there is no opportunity of making cuts in costs.

Actually, however, the strongest argument brought forward by the representative, one which cut the ground entirely from beneath the feet of the hauliers, was that a member of the local association, during the progress of the negotiations, sent' in a quotaktion ernbodying terms less than those for which the hauliers' were asking and not greatly differing from those which the 'farmers were offering. I have called this an argument. It is better (or worse, according to the point of view) than an argument. It is a hard, -incontrovertible fact and, I believe, constituted the rock upon which the hauliers' vessel of negotiation was wrecked.

The plea of this defaulting member—he must pardon me if the term appears too strong—was that he feared the entry of competitors from outside the area who would cut the proposed rates and deprive them of most of their winter's work. As that fear is clearly the weak link in any chain of rate fixing, it is worth while to examine it closely.

I can show that it is a factor of rapidly diminishing importance. Indeed, it may already have ceased to be of any consequence. The basis of my belief is the action taken by Mr. J. H. Stirk, the East Midland

Licensing Authority. Mr. Stirk took the first pas

sible opportunity, namely the first sitting following the agree-rnent, to announce the scale of rates to those assembled. He said that he would regard those rates as o minima and would consider that any haulier who quoted lower prices was rate-cutting ; he would take action accordingly. That, I think, is the most helpful attitude. It does not, however, quite meet the objection raised by the haulier who was, according to the stories I was told, largely responsible. for this schedule of rates being so low, inasmuch as, on the face of it, it would not be taken into consideration by hauliers coming from, say, Doncaster. (Thai was one of the towns mentioned in the discussion at Scunthorpe ; it is outside the

20 o Eastan area.

In fact, however, poaching by outsiders in that manner will be just as effectively stopped. It is well known that, from time to time, the Licensing Authorities meet and discuss such problems as this, brought about by interference between one area and another, and it is clear that this is a problem. which would inevitably come up for discussion on those occasions.

It is equally certain that a haulier who could be proved to have behaved in this manner would lay himself open to be told, 'when he applied for a renewal of his licence, that he was demonstrating that there was not sufficient need for his services in his own area, because he. was going outside for work and attnally cutting rates in order to obtain it His licence might,

therefore, well be refused. S.T.R.