AS THE CROW !S...4 CROSS EUROPE

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

AGREAT deal—perhaps too much—has recently been written about operating to Europe. The technical Press in particular has endeavoured to keep its readers informed of what is going on " E.E.C.-wise " in Brussels, and of what can be expected to be the effect on operators—C licensees and hauliers—when and if Britain joins the Common Market.

But there is a world of difference between theory (and most of •what has been written so far has been strictly theory) and practice; between what might happen on the Continent if Britain joins, and what is happening now. It was with this in mind that I recently accepted an invitation by the Crow Carrying Co. Ltd., of Barking, to accompany a tanker vehicle, driven by the company's most experienced " Continental " driver—Tom Crawford—on the second trip of what appears to be rapidly turning into a regular monthly run to north Germany, to bring back a load of liquid chemicals to a factory in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

It was felt that in this way—and only in this way—could readers be given an idea of how a British driver (and vehicle) could cope with the many difficulties to be encountered in the various countries of Europe.

The pick-up point of the vehicle that I accompanied was Bremerhaven, one of Germany's busiest North Sea ports, and it is interesting to note that, despite the fact that the sea journey between Bremerhaven and the English destination (which, incidentally, is on the North Sea coast as well) is much shorter, the customer required delivery by road because, one must assume, this method is more economic.

Despite the three frontiers that had to be crossed, involving the negotiation of six customs barriers and a night sea crossing between Antwerp and Tilbury, the load took just under three days (70 hours, to be precise) to get from the manufacturer's premises to the customer. The journey involved carrying the 3,500-gallon load a total of 728 miles-300 on the Continent, 168 sea miles on the ferry, and 235 miles in England. The journey by sea, I was told, usually takes 52 'hours, but this is governed by vessel availability and surface transport to and from the ports at each end. Similar commodities going by rail using the Hook of Holland/Harwich sea route, had oftentaken, I was told, 17 days to complete.

Apart from the time-saving factor, the economic scales gave an added advantage in this particular instance because the chemical product, when transported by sea or rail, has to be drummed. The bulk load carried by the Crow tanker would have required 70 drums costing DM 25 each—a total of £157 13s.—and the drums. 1 understand, are non-returnable.

The vehicle that Crow used on this run was a standard Atkinson rigid eight-wheeler, powered by a Gardner 150 b.h.p.

.72 engine, fitted with a 3,500-gallon two-compartment tank made by Andrews Brothers (Bristol) Ltd.

Apart from some excellent passing mirrors (which are essential on a vehicle fitted with right-hand-drive steering) and three extra red tall lights fitted at the rear of the tank, no special adaptations had been made to the vehicle to enable it to operate on the Continent. The tank body did not meet the necessary standard to qualify for a T.I.R. carnet, although Crow has operated the vehicle on the Continent for the past eight months. For operating abroad, of course, G.B. plates have to be carried, and the vehicle also carries a " 60 km." speed restriction plate. The wheels were Michelin shod, the twin tyres on both rear axles being connected with Carlair equipment to maintain an equal amount of pressure in each set of tyres.

Driver Crawford, having made about 15 trips to the Continent in the vehicle since last April, takes along with him an extensive supply of extras. For instance, a full set of bulbs are carried in special clips in the cab, together with two spare inner tubes, a fan belt, a lift pump, a spare emergency fuel suction line and a crowbar. Essential items for Italian travel are fire extinguishers, a red roadside warning triangle and lamps. He also carries with him several road maps which he obtained on the Continent, and a portable transistor radio—an essential personal item for keeping in touch with events at home.

The Bremerhaven trip turned out to be no straightforward "collect and deliver" operation. Because of a prolonged period of dense fog in England, and in London in particular, several sailings of the Atlantic Steam Navigation Company's two Continental ferries were cancelled. The original plan was for the vehicle to make the journey on the Friday night ferry to Antwerp. At the last moment, however, this had to be changed and Crow was advised to get its vehicle aboard the " Doric Ferry" on Thursday afternoon on the chance that it would sail that day for Rotterdam.

When this was arranged, Crawford and his tanker were at Southampton. The vehicle was rushed back to Barking, to enable the driver to collect some clothes, and then on to Tilbury where it was taken aboard the ferry during the afternoon. Because of the rush, the vehicle embarked with a dirty tank and arrangements had to be made for it to be cleaned on the Continent. However, the fog did not lift on Thursday, and the "Done Ferry" was not able to get away from Tilbury until 12.30 p.m. on the following day—Friday.

The ship arrived at Schiedam, the Rotterdam terminal, at 3 a.m. on Saturday and our first task after breakfast was to collect documents and money from the company's Dutch agents —Konig and Co.—who, like most of the agents on the Con

tinent, have offices on the quayside. Crawford collected a £60 "float" in Dutch currency, and the vehicle's pass for travelling through Germany (which, we noted with dismay, was due to expire at midnight on the following Monday). Other documents carried were the green international insurance certificate and an international carnet, suitably completed for the journey. One Dutch form was not to hand because, we were told, the appropriate office was closed and would not open,until the following Monday. Crawford decided he would chance his luck without it, and it is interesting to note that we actually completed our journey through Holland and across the border without being called on to produce it.

We next made our way through the busy streets of Schiedam to the premises of the Tankkercleaning N.V. for the tank cleaning operation—Konig had made prior arrangements for this.

At a temperature well below freezing point and with the roads and most canals covered with sheet ice, we left Schiedam and headed into Rotterdam in search of the Utrecht road. Due to the awkward placing of route indicators and signposts, which I considered to be too small, especially as they were often located on the opposite side of the road, we had to seek the help of policemen. We passed through the city centre and were soon on our way to Utrecht, some 52 kilometres (321 miles) distant. Although described on the map as a "motorway", we found the road to be single carriageway for

part of the way although it became a dual carriageway when we • joined the Hague-Utrecht road. The road was straight and flat— indeed, the .whole journey to Bremerhaven was on roads like this without incline or decline—passing under extremely low

bridges. It was on this initial stretch of fast road that I first realized the difficulties Crawford had to put up with. Apart from driving on the "wrong" side of the road, there was also the speed factor to contend with. The governed maximum speed of our Atkinson was 42 m.p.h. Most of the traffic encountered—and I include really heavily laden vehicles hauling large trailers— was travelling at 60 to 70 m.p.h. We were thus continually being overtaken by these larger and heavier vehicles, and those that were going slower we found hard to overtake because of the difficulty of seeing ahead and the uncertainty of being able to get past quickly. "I've got the power in the engine, and the right gearbox." Crawford shouted across his cab to me, " but the rear axle just won't give me the higher speeds ". Another thing he complained of was the numbness of his right leg through keeping the accelerator depressed for long periods. A band throttle, he thought, would be ideal for Continental work. Yet another irritation, I found, was the necessity of continually having to convert the simplest distances from kilometres into miles. I also had to think hard when we came to speed restriction signs in built-up areas. To get over this particular difficulty, Crawford has marked his speedometer off in kilometres, using sticky paper; he was unable to do anything about the mileometer. Manufacturers will have to think of this when supplying vehicles to operators who intend to use them on the Continent; two odometers are necessary.

At 2.50 p.m., after covering 125 miles, we stopped at a café in Hengelo for a meal of steak and chips which, with the cost of a glass of beer, amounted to the equivalent of 9s. The food was good and the proprietor spoke excellent English.

At Enschede—our last town in Holland—we took on diesel at a Shell garage. Crawford carried a letter from Kong which authorized any garage in Holland to supply fuel and credit Konig with the cost. We had no trouble here at all—Crawford had used the garage previously and was known to the attendants.

We crossed the Dutch-German border at Gronau. Joining a long queue of vehicles—mostly private cars—we moved slowly forward to the actual frontier gates. Apart from showing our passports to the Dutch authorities, no questions were asked about the vehicle. As soon as we crossed into Germany we drove into a vehicle park in front of the Customs office. Here we sought our agent, but found his office closed. We decided to go it alone. We changed all our money into Deutschrnarks at the exchange bank and then entered the German Customs office. After ascertaining verbally that the vehicle was empty (nobody bothered to look) and a cursory look at the documents, the officials allowed us to proceed. The total time taken from entering the Dutch Customs to leaving the German Customs was 55 minutes. "We were lucky this time," Crawford remarked as we drove away. "They can be real blighters."

By then it was dark and we decided to push on as fast as possible because we had been given to understand from statements in the Press that no commercial vehicles were allowed to run in Germany on Sundays. (We later found this not to be strictly correct because, apparently, vehicles carrying perish (4 ables and foodstuffs can run on Sundays, as also can commercial vehicles under a certain unladen weight.) The countryside was covered with frozen snow; the roads in this part of Germany we found to be narrow and rough, and we particularly noticed a lack of street lighting in towns and villages.

Sandwiches at 10s.

We stopped for food at Lingcn. The sandwiches we ordered turned out to be just ham and cheese on a plate, with two slices of bread. With coffee the cost was about 10s. each.

We then continued on our way deeper into Germany, through Cloppenburgh, through the vast city of Bremen, where again, because of confusing signposting, we sought the help of the police to put us on the right road, and so on to Bremerhaven.

Reaching our destination soon after 11 p.m., very cold and tired, we were welcomed, despite the lateness of the hour and no advance booking, at the Hotel Leick just outside Bremerhaven with the warmest of hospitality by the proprietor and his wife, who both spoke good English. After some excellent food and drink we turned in thoroughly exhausted.

So far as our job was concerned, Sunday was completely wasted, apart from finding the local weighbridge where we would have to weigh the vehicle, both loaded and unloaded, the following day. Otherwise it was a rest day for us.

On the Monday, after an early start; we weighed the empty vehicle and then went to the factory to collect our load. While the vehicle was being loaded—a slow procedure because of the small diameter of the factory's loading pipe—we enjoyed free coffee in the works canteen. We then made our way back to the weighbridge, accompanied by an English-speaking clerk from the factory, to ascertain the weight of the load-13,740 kilos (about 13 tons). After obtaining weight certificates, the clerk took these, plus the delivery notes and other documents, into the nearby offices of a " spedition agent" who prepared all the Customs documents required for the return journey.

We ran into some typical Continental difficulties when we were asked to convert the load's volume into weight and express it in kilogrammes—a difficult task, I thought, for the average driver (and for this journalist, at least!).

After paying our hotel bill for two days' bed and breakfast and one evening meal (£2 3s. each), we finally left Bremerhaven at 11 a.m. on Monday, with the uneasy thought in our minds that we had to be out of Germany before midnight, when our German pass expired. A close study of the map told us that we could cut the mileage considerably and avoid Bremen if there was a ferry (none was shown) across the river Weser. Inquiries revealed that there was such a ferry between Dedesdorf and Kleinsensiel, and we set off for Dedesdorf at top speed. We crossed on the ferry without delay and made our way to the nearest border crossing point at Nordhornvia Brake, Oldenburgh, Ahlhorn, CloPpenburg and Bogen.

Negotiating the customs with a loaded vehicle proved a far different proposition from going through empty, although at Nordhorn we were assisted by Crow's agent, Gerlach and Co. The English-Speaking clerk took our papers from us, calculated the tax, took the money off Crawford, and took us through the German customs without bother. Seals were affixed to the outlets and inlets of the tank (giving us partial coverage) and we were then allowed to move the vehicle across the frontier, The German tax was DM 188, 35 pfg. (just over £17) for one day's travelling.

Next we entered the Dutch customs office where we were asked for the tare weight of the vehicle in kilos (again, more hasty calculation). The Dutch tax, based on the unladen weight of the vehicle, for two days' operating was 41 guilders and 18 cents (about £4). Six more seals were placed over the tank openings by the Dutch and then we were allowed to proceed. Total time taken crossing the border was I hour. 10 minutes. We were surprised to note that a Danish vehicle with a T.I.R. carnet that entered the German customs just ahead of us, took exactly the same time to negotiate the frontier.

On the Dutch side of the frontier we decided to eat again— and this time we paid heavily for it. The steak, mushrooms, chips, peas and onions cost no less than 19 guilders 80 cents (£2) for the two of us.

At this stage it became obvious that we would be able to reach Antwerp in time to catch the Tuesday evening ferry to Tilbury, and so, after passing through Hengelo, we left the main Rotterdam road and turned south for Belgium. via Arnhem and Nijmegen. On this road there are several "bed and breakfast" establishments specially catering for the transport drivers and

it was at one of these that we stayed for the night. The food was good, as indeed were the beds, and the cost was very reasonable indeed-5 guilders 50 cents (10s. 6d.) each, which included an evening meal and bed and breakfast.

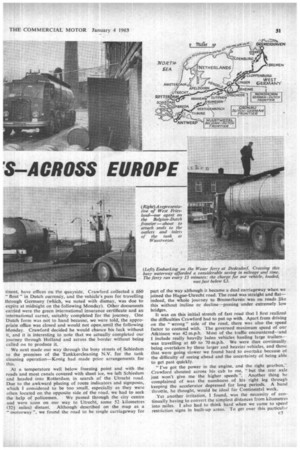

On Tuesday morning we set off at 7.15 in pouring rain. After refuelling outside Arnhem, we made our way along a good dual-carriageway motorway to Nijmegen. We crossed the famous Maas Bridge, and passed on in a south-westerly direction through 'S-Hertogenbosch, Tilburg and Breda and on to the Dutch-Belgian border at Wuustwezel—a border apparently noted among drivers for delays and pettiness on the part of the Belgian customs officials—it being the only border crossing point for vehicles passing between north-west Europe and the port of Antwerp.

We parked in a very long queue of vehicles from all over Europe, and sought out our agent—West Friesland*—to take

us through. Then the trouble started. After passing quickly through the Dutch customs unchallenged, it was discovered that a certain Belgian permit was missing. After a great deal of telephoning and discussion, our courier took us into the main Belgian customs office where we waited, together with some 20 to 30 other drivers, while our forms were passed from one official to another, being checked, stamped, and then rechecked and restamped. Then out into the rain and across the road to change our money and back again to yet another office where the Belgian tax was calculated. This time we had to part with 410 Belgian francs (£2 18s.) for running in Belgium for only a couple of hours. Eventually, after yet a further set of seals was attached to the tank, we were allowed to pass— it had taken exactly 1 hour and 35 minutes to get through.

We left Wuustwezel at 3 p.m. and arrived in Antwerp at about 4.30. By 5 p.m. we were once more on board the familiar and friendly "Done Ferry" which sailed just after 6 p.m.

The rest of the story is a simple one. In company with several other drivers returning to England from Belgium and Italy, plus some Danish drivers bringing horses here from Sweden, we relaxed in the comfortable surroundings of this ship, which provides excellent accommodation, including firstclass food and service.

After a fairly rough night at sea, which would have been far worse but for the vessel's stabilizers, the ship docked at

Tilbury at 9.25 a.m. on Wednesday. Here, surprisingly enough, because of a documentation hold up, the vehicle and its load were delayed at the British customs for several hours, but clearance was given before noon and the vehicle went on its way northwards.

The load was delivered in Yorkshire at 9 o'clock the next morning—Thursday—to the amazement, I understand, of the customer.

It is this sort of service that gives road transport its hold. This was a normal, routine trip, with nothing special laid on

to impress me. I was impressed nevertheless, especially by the all-round ability and resourcefulness of a driver who spoke only English. So far as the job itself was concerned, this proved no handicap and the presence of a company driver with his " own " vehicle throughout the journey is an important balancing factor.

There arc undoubted advantages in using the more-popular artic for Continental work—for example, a saving in ferry

charges, and the use of tractive units especially suited to work in their own countries. But taking into account such things as vehicle preparation (including supervision of tank cleaning in this case), vehicle and load security, and the making of

on-the-spot decisions regarding routes and ferries to cut journey times to a minimum, there is a great deal to be said for using

a rigid with company driver for the whole trip. Certainly I, for one, was not surprised to see that this type of vehicle is apparently gaining more popularity for cross-Channel work.