EXERCISE IN INTEGRATION

Page 140

Page 141

Page 142

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ROAD transport owes much of its success to the ability to meet immediately the changing and exacting needs of trade and industry. To this end operators concerned in the movement of goods by road must be fully conversant with the particular characteristics of the varied types of traffic they move.

Bulk movement of granular traffics is an excellent example of the extent to which road transport must physically integrate the service it provides with the process of production and despatch. But at the same time it re-emphasizes the dependence, and rightly so, of road transport on its customers—trade and industry. Thus, if such be the case, operators must accept a slower rate of growth in such bulk movement if, in practice, their customers find that the adaptation of intake and discharge facilities presents more problems than the provision of specialized vehicles by the combined efforts of transport and vehicle manufacturing industries.

Nevertheless growth in the change-over to movement of granular traffics in bulk continues. Moreover because this traffic originates substantially in staple industries such changes once made must

BY S.. BUCKLEY,

Assoc Inst T have substantial and lasting effect on the customer's transport requirements and the type of service necessary to meet those requirements.

Agriculture and allied trades are typical examples of such staple industries. Likewise barley, in its natural or processed form, is a typical example of a granular product suitable for movement in bulk. So to find out just how the change-over to movement in bulk in this type of traffic was progressing, I discussed recent developments with Mr. G. A. G. Haworth, group transport officer, Associated British Maltsters. With headquarters in Newarkon-Trent this organization has makings adjacent to most of the barley growing areas of England and subsequently makes deliveries to breweries, distilleries and other customers throughout Britain.

First, however, it is necessary to get into true perspective what is a reasonable rate of growth to expect in bulk movement in the malting industry. The age-old sequence of lifting barley at the farm, delivering it to the malting and subsequently re-delivering it as malt to the brewery or distillery is inherently traditional. Throughout several centuries the overall movement has .centred around the ubiquitous sack. Over the same period despatch and storage premises at the farm, malting, brewery and distillery have been built accordingly.

It is against such a background that the movement of grain in bulk is being introduced. Inevitably in assessing whether the rate of growth in bulk movement is reasonable any valuation as to whether this is slower than might have been expected is largely relative.

Because many of the premises to which bulk deliveries have to be made are old or at best are an adaptation of old premises the maltster has to be prepared for differing methods of intake at the customers' premises. The simplest facilities consist of virtually a hole in the ground into which malt is delivered from the vehicle by gravity. Alternatively some form of suction might be installed at the receiving point and in one instance, Mr. Haworth said, by pressure. Consequently even on their dual purpose vehicles which permitted the carriage of sacked loads in addition to bulk a blower was also necessary if all means of discharge were to be accommodated.

But whilst technical developments of both vehicles and facilities at discharge points would continue and improvements accordingly be incorporated in future designs, Mr. Haworth considered that changes within the structure of the malting industry and that of its customers could have as great an effect on the growth of movement in bulk. Within their own organization modern large scale production units had been built in recent years with capacities far exceeding the old traditional malting. These new maltings—or malt factories to use a more appropriate term—were eminently suitable for loading of vehicles in bulk. Moreover modern malting techniques had eliminated the previously seasonal nature of the work. As a result production continued day and night and the opportunities were therefore available to correspondingly load vehicles over a 24-hour cycle. Where this was put into effect it could be done more easily if vehicles were loaded in bulk rather than have the necessary labour available throughout the same 24-hour period to put malt in sacks in the traditional method.

I asked Mr. Haworth whether the opportunity afforded by the new Construction and Use Regulations to operate larger goods vehicles was likely to accelerate the employment of bulk vehicles in this industry. In reply he said that larger vehicles would be employed but one of the snags in their trade was the limited approach to the discharge points at many of their customers' premises. As an indication of the present ratio of malt being moved in bulk by their group for delivery to customers, Mr. Haworth said their first bulk vehicles began to operate around 1955. After experience with prototypes, movement of malt in bulk in the last five years has more than doubled and delivery is now being made to more than 20 customers of the relatively limited total within the brewing industry.

Correspondingly the ABM fleet of road vehicles now includes 22 with bulk bodies of relatively large carrying capacity as compared with 55 platform vehicles with capacities of around 7 to 12 tons.

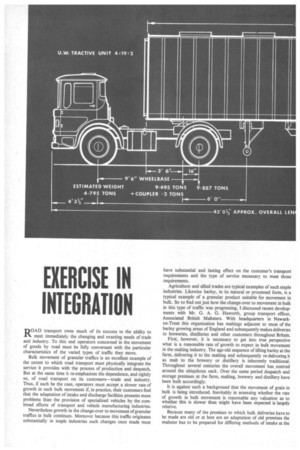

As already reported in COMMERCIAL MOTOR extensive use is made by ABM of the moving bulkhead made by Murfitt Bulk Transporters, Wisbech, and early this year they expect to put into service a 32-ton vehicle of this type. It will be an articulated outfit with an AEC Mandator tractive unit fitted with six-speed gear box and AV 691 engine. The trailer will be a Murfitt frameless bulk transporter fitted with MurfittiSchmitz triple axle steering bogie and the body will again have a moving bulkhead. The whole outfit will run on Michelin D.20 10.00-20 (16-ply) single tyres and will be plated at 32 tons g.t.w. giving a capacity of 1,650 Cu. ft.

The rationalization of production within the ABM group naturally results in a substantial reduction in the number of manufacturing centres whilst a similar reorganization is taking place in the brewing industry. The ultimate pattern would therefore be a heavier flow of malt between fewer centres. Here again this should encourage movement in bulk. Additionally it could encourage such move ment by professional hauliers although little is at present moved on A-licensed vehicles.

One of the reasons for this limited movement of malt in bulk in A-licensed vehicles is the fact that this product is particularly susceptible to moisture. Accordingly the relatively simple adaptation of what is basically a tipping vehicle with some form of tilt or tarpaulin arrangement which might suffice for other grains is not adequate for malt. Therefore a more sophisticated bulk vehicle is necessary with an inevitable substantial increase in initial outlay. To justify such outlay a haulier needs to be assured of both adequate and relatively permanent flows of traffic. However as rationalization within the malting and brewing industries proceeds hauliers may consider that the situation has changed sufficiently to reassess possible opportunities for carrying such traffic.

In view of malt's susceptibility to moisture I asked Mr. Haworth what the potential was for sending malt in bulk vehicles on to the Continent bearing in mind that export of malt is of sufficient proportions to justify a separate export organization within the ABM group. Despite the publicity given to roll-on/roll-off facilities made available by Continental ferry services in connection with the movement of other types of traffic Mr. Haworth said that the cost would be prohibitive in the case of malt. Such movements by traditional methods involving the use of rail and shipping services has become highly organized and competitive. Moreover from the shipping companies' point of view malt was looked upon as good cargo which could be readily stowed when conveyed in sacks or similar containers and accordingly justified a competitive rate.

As an example of the many factors which are involved in the change-over from traditional methods of movement to bulk delivery, the question of standard loads arises in connection with the malting industry. The basic unit is a quarter of malt and the quantity commonly ordered is a multiple of 50 qrs. (7+ tons) or 100 qrs. (15 tons). In the early stages of introducing bulk delivery an endeavour was made to continue to supply loads in multiples of 50 qrs. where the customer so ordered.

Inevitably, however, the combination of the increased unladen weight of a fully equipped bulk vehicle and the requirements of existing Construction and Use Regulations meant that multiples of 50 qrs. could not always be achieved. Equally underloading of such expensive vehicles could not be accepted and traditional habits in ordering have in many cases given way to the requirements of economic operation.

Alternative methods

Earlier mention has been made of alternative methods of discharge. Although such bulk facilities are being provided at receiving points, the rate at which the malt is then taken away has not always been speeded up sufficiently to allow successive vehicles to discharge after a reasonable interval of time. In some cases this may be due to a failure to appreciate the overall significance of changing over to movement in bulk. But it can also result from the fact that many of the premises involved are old and acceleration of movement within themtven though accepted as a desirable link in the conversion to bulk movement is nevertheless a physical impossibility without drastic and expensive constructional alterations. Indeed it is often at this very point that the construction of a completely new set of premises might seeem the better solution.

But whilst such decisions are primarily not within the realm of transport they must obviously affect the rate at which the changeover to movement in bulk proceeds.

Mr. Haworth agreed that an associated advantage of the swing over to movement in bulk concerned the problem of labour. It was generally conceded that recruitment of experienced drivers capable of handling a vehicle and load with a combined value of £10,000 or more would become increasingly difficult. Additionally it would become more unlikely that staff as they approached the age of retirement would be capable and willing to load and unload by traditional manual means possibly 200 sacks of malt each weighing 11 cwt. which constitute a 100 qr. load. But the advent of delivery bulk would ease, if not eliminate this problem. Accordingly experienced staff, once recruited, could be ensured of continued employment until retirement. Moreover it would benefit the employer in that such retention of long-service staff would invariably mean that their detailed knowledge of delivery requirements would ensure that customers' needs were being fully met.

Because agriculture is so closely allied to the malting industry I next went along to the National Farmers Union to get the views of their transport officer Mr. E. W. Bebbington as to developments in bulk delivery in agriculture.

Agreeing in general principle with my contention that the extension of bulk delivery has not been as rapid as some had expected in the immediate post-war years he considered there were many reasons for this. In contrast however, some closing of railway branch lines although a negative action in itself was resulting in some instances in the bulking of traffic by farmers within the areas concerned. This had led to the purchase of vehicles by a group to serve the needs of members in those areas.

Economics of bulk delivery

The economics of bulk delivery when applied to agricultural products needed to be considered in the wider context of a farmer's yearly needs. Inevitably much of his production was tied to the natural harvest Of any particular crop. Accordingly in some instances movement at a particular time was so vital to the farmer that he must be assured of getting a vehicle just when he wanted it. The only way of doing this in some instances was for the member to provide his own even though it may operate less than 20 weeks in the year. If it was not available a year's work could be lost virtually overnight. In fairness to the professional haulier however Mr. Bebbington said it must be admitted that it was a tall order to expect him to produce a vehicle out of the bag on the spur of the moment.

Regarding the share-out or bulk movement-of grains as between rail, professional haulier and the C-licence operators, the present position was that the preponderance was carried by the C-licensed vehicle in the name of the long established corn and agricultural merchants.

The buying and selling of grain was a highly complex and organized business and whatever economies could be obtained by the use of bulk vehicles such movement could not readily be allowed to substantially alter existing procedures.

Mention of difficulties in applying bulk movement for this type of traffic does not infer that its growth will not continue. Rather it is intended that the difficulties should be realized and provided for before turning over to movement in bulk.

Thus at the original point of collection, namely the farm, where a bulk vehicle is making several trips from farm to malting or mill, as directed by the corp merchant, it is often difficult for the farmer to know exactly the quantity leaving his farm on each trip. The likelihood of a weighbridge of adequate size being available either it the farm or in the immediate vicinity is small. Moreover with the closure of many branch lines even the weighbridges at former wayside stations are no longer available. As a result, the farmer often has to rely on the weight recorded by buyer or his agent. An additional point is that where a large bulk vehicle is making several successive trips the reducing amount of fuel in the tank requires an increased payload if the same gross weight is to be maintained.

Weighbridges, therefore, may well play an important part in the further development of the movement of grains in bulk and, indeed, other granular traffic. The existing location of public weighbridges would seem to follow no regular pattern other than those provided by a diminishing railway system. Even before the closing of branch lines many transport operators would agree that the provision of such weighbridges was geographically inadequate.

For the future, however, Mr. Bebbington drew attention to paragraph 59 in part II of the recent White Paper on Road Safety Legislation 1965-6 dealing with Safety Measures for Goods Vehicles. This reads:—"It is essential that the new plated weights should be effectively enforced, and more weighbridges provided for this purpose. Ministry of Transport staff will increasingly regard the check-weighing of vehicles as part of their functions. The pattern of enforcement will depend in part on the results of trials with modern types of weighbridges. These trials will start in 1966."

Whilst this paragraph relates primarily to the safety of goods vehicles it would seem that intended provision of a new network of weighbridges for use by Ministry of Transport examiners could be put to a wider commercial use in the interests of improved transport facilities for trade and industry.