FARMING WI' 1-1 NEW BEDFORD OILER

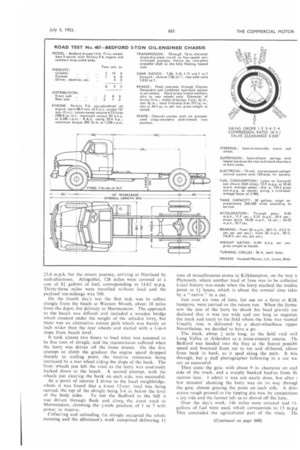

Page 78

Page 79

Page 80

Page 81

Page 96

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By Laurence J. Cotton,

TESTING a Bedford A-type lorry for five days and covering 860 miles, with varying degrees and types of load and diverse operating conditions, provided greater scope for criticism than the normal one-day trial, which is usually limited to 100 miles with a full load all the time. I was provided with a long-wheelbase chassis having a Perkins P6V engine and the extended trials included high-speed trunk hauls from Luton to Cornwall and return, and local work in which 15 stops were made in li miles when making deliveries to a small village. A small proportion of the work was unsuitable for the type of body, but, in general, the Bedford was a good, powerful, all-round truck and notably economical.

Introduced in the Bedford range four months ago, the A-type 5-tonner is a successor to the OLBD model, but retains the well-tried power and transmission units of the former model. Installing the Perkins engine on the assembly line is new to the Luton factory and the unit is supported on a conventional sandwich rubber-bonded plate at the front and by trunnions in rubber bushes at the rear. These trunnions are arranged on opposite sides of the dutch housing and absorb torque reaction. A 12-in.-diameter 'clutch is used when the oil engine is fitted.

One of the major alterations in the design of the A-type is the provision of an all-steel normal-control cab and the use of a longer frame, in which the engine is mounted about 6 in. farther forward than originally. The alteration of the engine position, coupled with the adjustment of the wheelbase, has enabled a better load distribution to be attained and longer springs have added to riding comfort. Shock absorbers, which are optional, were fitted to the test vehicle and in 860 miles of driving, with and without load, I found no cause to criticize the suspension.

The chasgis was not new, having covered over 10,000 miles, including a period on the Vauxhall Motors bump circuit, but there was no squeak or raffle in the cab assembly when starting the journey from Luton to Morwenstow, Cornwall, carrying a concrete-block pay-load. Early-morning traffic hindered progress in the initial 30-40 miles, but from Egham onwards it was mostly full-throttle driving, apart from town work.

The Perkins high-rated unit, developing 83 b.h.p. at 2,400 r.p.m. and 202 lb.-ft. torque, provides a lively performance in the Bedford 5-tanner and the high governed speed is an aid to acceleration and hillclimbing. Although not so apparent with the advocated payload and on the average gradients encountered en route to Exeter, there were occasions in the hillier parts of Devon and Cornwall when an intermediate ratio between second and third gear could have been used to some advantage.

I give full credit to the synchromesh gearbox, which enabled rapid gear changes to be made on the inclines with minimum loss of road speed. The maximum speed —43 m.p.h. on level ground—was maintained for long periods and on the declines the Bedford was often travelling at 50 m.p.h., having run through the governor. Perhaps more to punctuate the journey and for inward refreshment than because of need for a rest, stops were made at 80, 140 and 170 miles from the start, but there was no discomfort in driving over 200 miles continuously, the final 90 miles being without stopping.

The A-type cab is a great advance in crew comfort, having ample room and good ventilation, and with the engine well isolated by partitioning and insulation there is remarkably little noise and no heat. My codriver for the week, Mr. Gordon East, of the Vauxhall commercial vehicle experimental department, noticed an unusually long and laborious gradient at Buckland St. Mary, near Ilminster, and three climbs in succession were made over the peak of the Blackdown Hills to check engine cooling.

After seven minutes' continuous second and third-gear work, the radiator boiled and the oil temperature rose to over 200° F. At first, it was thought that more suitable territory had been found for cooling tests than the normal Chilterns circuit used by Vauxhall Motors, but investigation showed that no water was being pumped to the radiator header tank.

A blocked top water hose was the cause of the overheating and when this was remedied, more normal temperatures were recorded on the ensuing climbs. After rectification, there was no occasion when the water temperature exceeded 160° F. during the five-day trials, although at times the vehicle was subjected to drastic tests, which could have caused overheating.

After a slow start, the average speed on reaching Exeter was just over 30 m.p.h., but the narrow roads and hills from Okehampton to Kilkhampton again reduced speed. The journey took 10 hr. 32 min., which included stops, but deducting standing time, the average running speed worked out to 29.6 m.p.h. With 17 gallons of fuel used in 281 miles, the consumption return was 16.5 m.p.g.

The next morning we donned working kit and unloaded the concrete blocks before breakfast, in readiness for three days' agricultural work arranged by R. Heard, Ltd., Morwenstow. Reporting for duty at 8 a.m., the Bedford was loaded with 1 tons of poultry food and solid fuel for delivery to houses and farms about 8 miles from the depot. The final call was to a farm having a 9-ft.-wide gate set directly on the side of a 12-ft.-wide road. Here, inability to see the near-side wing, coupled with the length of the chassis and wheelbase, added to the difficulties, especially as the standard body is 7 ft. 6 in. wide overall and juts out from behind the cab.

Having successfully negotiated the gate posts without damage, there followed a 100-yd. narrow approach to the unloading point. From there it was necessary to reverse to the road.

The next load was six tons of potatoes to be collected from the Budc railway siding for delivery to the same farm. The wide body is an advantage when carrying potatoes, because the sacks can be stacked six abreast and 66 can be put on the bottom row. Although I drove at first with more than normal care, because of the high load, the lorry was quite stable, even on the steeply cambered roads in Stratton.

Another four tons of miscellaneous agricultural equipment were collected from the Budc sidings when returning to the Morwenstow depot and to test the capacity of the vehicle to climb freak hills. 1 drove along the coast road which, although a little shorter than the normal road through Kilkhampton, involves a longer journey because of a gradient which rises 400 ft. in just over half-a-mile. With only part-load on board, the Bedford made fairly easy work of the climb, using, of course, the machine's low gear.

A slight knock, which was accompanied by hunting when idling, developed in the engine. The symptoms, to art uninitiated driver, would be similar to a big-end knock on a petrol engine, coupled with an indifferent sparking plug. My diagnosis was a partially choked injector nozzle or temporarily seized needle, which might have been correct, because after a few miles of full and part-throttle driving, the noise disappeared and the idling was back to normal.

After a belated lunch we loaded five tons of pig and poultry food, fuel, potatoes and binder twine for delivery to 15 houses and smallholdings in the neighbouring village of Gooseharn. The total distance between the first and last calls was only 11 miles, but with considerable shunting and reversing in the narrow lanes the fuel-consumption rate must have been fairly high. In the day's work 50 miles were covered, of which 16 were without load, as the local filling station for oil fuel was three miles from Morwenstow and other short journeys for personal transport were necessary. Assessed in hauliers' terms, a total of 1231 payload ton-miles were run at a cost of four gallons of oil fuel. The average fuel return for the day was 12.5 m.p.g. Considering the extremely hilly area of operation, and the short journeys with many stops, this was an economical result.

In the evening, we loaded 102 bags of barley, weighing 5 tons 2 cwt. in readiness for an early-morning delivery to a mill at Lifton, which is 31 miles from Morwenstow. The first 15 miles were fairly easy going along quiet country roads, but after this the route was continuously undulating and required prolonged use of the brakes or indirect gears. Although a double-bank load was carried, the Bedford rode well, as is indicated by the fact that the journey was completed in 1 hr. 9 min.

Unfortunately, the time saved on the journey was lost while waiting to unload. In the interval we assisted in unloading sacks from a contemporary model, so that I had an opportunity of comparing the merits of the normal timber body floor and the type with metal strips which is used in the latest Bedford. There are disadvantages attached to the Bedford method. It would be preferable to have a tread-pattern metal strip, which would prevent sliding when walking along the body, and it is difficult to discharge a bulk load because the strips stand proud of the floor. My choice is the conventional full-timber floor, which can be easily swept, and does not impede the use of a shovel.

After delivering the barley there was a 26-mile trip unladen to collect lime from a Plymouth quarry. This journey was covered in an hour, after which we joined the queue to load from a hopper. The return load amounted to 5 tons 16 cwt. of loose lime, which was well damped down before leaving, to avoid inconvenience to other road users. This was carried 64 miles through the hillier part of Devon into North Cornwall. The brakes took severe punishment in maintaining a high average speed and there was judder from the near-side rear wheel for a period on a long down gradient. During the luncheon stop the adjustment of the brakes was checked and I found that the mechanical jack and kit of tools supplied left much to be desired. There was no need for further adjustment and in the remainder of the journey and to the end of the five days trials there was no return of the juddering. It is probable that the trouble was caused by maladjustment of the shoes and slight ovality in the brake drum. Again the Bedford showed its paces by averaging

Jo,

23.4 m.p.h. for the return journey, arriving at Hartland by mid-afternoon. Altogether, 128 miles were covered at a cost of 81 gallons of fuel, corresponding to 14.63 m.p.g. Thirty-three miles were travelled without load and the payload ton-mileage was 540.

On the fourth day's test the first task was to collect shingle from the beach at Wanson Mouth, about 18 miles from the depot, for delivery in Morwenstow. The approach to the beach was difficult and included a wooden bridge which creaked under the weight of the unladen lorry, but there was an alternative retreat path which was barely an inch wider than the rear wheels and started with a 1-in-4 slope from beach level.

It took almost two hours to load what was assumed to be five tons of shingle, and the transmission suffered when the lorry was driven off the loose stones. On the first attempt :to climb the gradient the engine speed dropped sharply to stalling point, the tractive resistance being increased by a rear wheel riding the slope of the bank. The front wheels just left the road as the lorry was cautiously backed down to the beach. A second attempt, with the wheels just clearing the bank on each side, was successful.

As a point of interest I drove to the local weighbridge, where it was found that a 6-ton 12-ewt, load was being carried, the top of the shingle being 3-4 in. below the level of the body sides. To test the Bedford to the full it was driven through Rude and along the coast road to Morwenstow, climbing the j-mile gradient of 1 in 7 with power in reserve.

Collecting and unloading the shingle occupied the whole morning and the afternoon's work comprised delivering 1-j tons of miscellaneous stores in Kilkhampton, on the way ti Plymouth, where another load of lime was to be collected Local history was made when the lorry reached the loadim point in 11 hours, which is about the normal time take' by a "native" in a car.

Just over six tons of lime, for use on a farm at Kilk hampton, were carried on the return run. When the farme saw the size of the lorry he shook his head gravely am declared that it was too wide and too long to negotiati the track and entry to the field where the lime was wanted Usually lime is delivered by a short-wheelbase tipper Nevertheless, we decided to have a go.

The track, about 1 mile long, to the field vied witl Long Valley at Aldershot as a cross-country course. Thi Bedford was headed into the fray at the fastest possibl• speed and bounced from rut to rut and slithered, almos from bank to hank, as it sped along the path. It woi through, but a staff photographer following in a car wa not so successful.

Then came the gate, with about 9 in. clearance on cad side of the truck, and a steeply banked lead-in from th narrow lane. I admit it was not easily. done, but after few minutes' shunting the lorry was on its way througl the gate, almost grazing the posts on each side. A drivi across rough ground to the tipping site was, by comparison a joy ride and the farmer left us to shovel off the lime.

Over the day's work, 146 miles were covered and I gallons of fuel were used, which corresponds to 13 m.p.g This concluded the agricultural part of the trials. Thi return to Luton was made with the St tons of concrete blocks and the 264-mile journey covered at 29.65 m.p.h. average speed.

Taken over the week, 885 miles were covered on 584 gallons of fuel, which is equal to 15.2 m.p.g. Just under a quart of engine oil was required during the week and, apart from brake inspection, no mechanical attention was given. There was increased free-pedal movement in the foot brake towards the 800-mile mark, but adjustment would have restored full efficiency.

At no time was the Bedford used sparingly. Except when descending the sharper and more torturous hills in B38 North Cornwall, the brakes were used to retard the speed and at other times the accelerator pedal was hard down on the floorboards.

Three men were in the cab for over 300 miles of the trials, but they were seated in comfort. The improvement in cab accommodation has been achieved without sacrificing load space and, in general, the new lorry is superior to its predecessor. Its manceuvrability is slightly impaired by a little larger turning circle (56 ft.), and with the longer chassis, more space is required for garaging. These points arc, however, of no great significance in connection with general operation.