T E TRIALS

Page 32

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

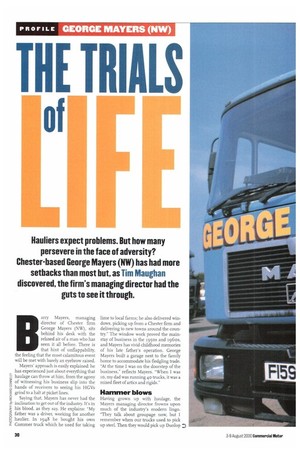

Hauliers expect problems. But how many persevere in the face of adversity? Chester-based George Mayers (NW) has had more setbacks than most but, as Tim Maughan discovered, the firm's managing director had the guts to see it through.

arty Mayers, managing director of Chester firm George Mayers (NW), sits behind his desk with the relaxed air of a man who has seen it all before. There is that hint of unflappability,

the feeling that the most calamitous event will be met with barely an eyebrow raised.

Mayers approach is easily explained: he has experienced just about everything that

haulage can throw at him, from the agony g of witnessing his business slip into the

hands of receivers to seeing his HGVs grind to a halt at picket lines.

Saying that, Mayers has never had the .6" inclination to get out of the industry. It's in k his blood, as they say. He explains: "My .2 father was a driver, working for another ghaulier. In 1948 he bought his own E Commer truck which he used for taking

lime to local farms; he also delivered windows, picking up from a Chester firm and delivering to new towns around the country." The window work proved the mainstay of business in the 1950s and 19605, and Mayers has vivid childhood memories of his late father's operation. George Mayers built a garage next to the family home to accommodate his fledgling trade. "At the time I was on the doorstep of the business," reflects Mayers. When I was to, my dad was running 40 trucks, it was a mixed fleet of attics and rigids."

Hammer blows

Having grown up with haulage, the Mayers managing director frowns upon much of the industry's modern lingo. "They talk about groupage now, but I remember when our trucks used to pick up steel. Then they would pick up Dunlop 0 D shoes which would be loaded on top of the steel. Groupage is a buzz word today—but it has been around for years."

Mayers recalls the days when the firm's HGVs would depart base on a Monday, do 4o drops around the UK, then return on a Saturday. He himself joined the firm in 1976, working as a fitter. By then George Mayers (NW) had moved to a larger depot in Chester, which is still the firm's home today.

It was not the best of times. "In the 1970s the firm went downhill. The window firm we had been carrying for got its own haulage and some of our drivers were stealing the Dunlop shoes," remarks Mayers. "This was costing us a fortune in claims from Dunlop."

By the late 19705 industrial action was also ravaging the Mayers operation, with the drivers' strike disrupting work and picket lines at Shotton stifling steel haulage from the site. The combination of the two was a hammer blow: "It crippled us," says Mayers.

Rationalisation was the only option. But things picked up in the 198os, with the firm shifting steel again as well as paper. Keith, Barry Mayers' brother, joined the firm. The two brothers and father George concentrated on building up the business again.

But there were more obstacles ahead. George Mayers died in 1985, a wrenching experience for any son. Barry took the reins in 1988, but in 1992 the company went bust. "Keith wanted to leave, so I had to buy him out," Mayers recalls. "I was strapped for cash, and the wages were rising. Plus, overheads were increasing and the VAT bill had to be paid.

"We went into receivership. There were so many things that happened. It was a nightmare, I went through hell." There were knock-on effects for other parties. "We had employed a lot of subcontractors as well," reports Mayers. At the time of receivership, the firm was running rz trucks, some of which were sold off. Mayers says: "The receivers came in and kept the work going with just two vehicles."

Redemption

The receivers were there for a month. Salvation came in the form of a loan from Mayers' father-inlaw. This allowed the firm to claw its way back, buying eight trucks used in general haulage. The fleet size is the same today, with the eight MANs, ERFs and Fodens making up the traction capability, pulling 16 trailers including curtainsiders, flats and coilers. And buying policy is strictly secondhand. "I used to buy new, but I was paying back L10,000 a month on hire-purchase. You can pay a tenth of the cost of a new truck—buying second-hand is the best policy."

Much of the work today is in transporting wire the length and breadth of the UK for a single customer; Mayer trucks have been hauling these consignments for six years. By providing a solid, reliable service the firm has the security of a contract with this wire com pany. "It keeps us busy," says Mayers.

Then there is general haulage, carrying goods such as raw materials for the building trade to destinations across the UK. Like many managing directors of small operations, Mayers recognises the need to liaise with customers. He often mucks in himself, getting behind the wheel when necessary. "Personal service is important," he says.

Adapt to survive

The adage "speculate to accumulate" is not something adopted by Mayers. As he has learned, life has a strange habit of taking a turn for the worst. For that reason he uses the services of subbies, enabling him to adapt to his market at a moment's notice; sometimes they may account for just 5% of work, at other times the subcontractor fleet may represent 40% of business.

Mayers believes a haulage firm of his size is going to find it increasingly tough in the future. The bigger firms have the means to employ staff such as DGSA and HSE specialists. The owner-driver has a solid workhorse identity, taking loads from A to B. In short, both parties can play to their strengths. The problems are for those firms which fall in between. The George Mayers (NW) story highlights the unpredictable nature of market forces and industrial action. The best policy is to structure work so that the key elements which ensure cashflow are not threatened.

Mayers says: "Don't get yourself lumbered with finance that you cannot afford to pay back, and make sure you get your trucks out on the road. Also, backload as much as you can. And you have always got to have plenty of trailers, which give you more flexibility."

After the ups and downs, Barry Mayers may not be rich but his firm is still providing an income. "We are not making a lot of money but at least we can say that we are on the right side of things."