HIGH AXLE RATIO BY BIG ENGINE

Page 32

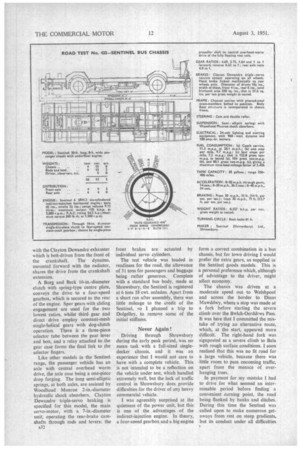

Page 33

Page 34

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

says

1. J. COTTON

M.I.R.T.E.

pERCHED on a 2-ton iron weight attached to an 8-ft-wide chassis travelling at 50 m.p.h. along a road flanked by ditches, could be a nerve-racking experience, but my ride as passenger on the Sentinel under such conditions can merely be described as exhilarating. At the wheel of the chassis was Ted Stevens, one of the burliest testers I have yet met, who knew the capabilities of the vehicle and had complete faith in its braking and fastcornering characteristics. Equipped with a 4.8-to-l-ratio axle, the performance was good when 'climbing the famous Dinas Mawddwy Pass, Merioneth, when the chassis was loaded to 101 tons, which is equivalent to a fullcomplement of passengers in the complete coach with a generous allowance for baggage.

Judging from its performance during the 180-mile test, the Sentinel should be good for fast, longdistance coach service, especially in the hillier areas where the 135 b.h.p. engine can be used to advantage. I had a chassis straight from the assembly bay, therefore the initial friction was high because the Shrewsbury models, being hand made, may take up to 2,000 miles before ihe various bearing surfaces become fully bedded down. The fuelconsumption rate was slightly above average and this was more noticeable during straight running, than when making four stops to the mile. Because of the engine power available, the high-ratio axle would be no detriment to short-stage work in most areas.

The 15-ft. 7-in.-wheelbase passenA30 ger chassis with six-cylindered engine forms a recent addition to the Sentinel range. It is built to receive 30-ft. by 8-ft. bodies:and is equipped with 9.00 by 20-in. tyres of 12-ply rating.

In common with all other models made at Shrewsbury, it has the horizontal power unit arranged between the frame side members below floor level. The side members, which are parallel and level from front to rear, incorporate the body floor structure which is assembled with central longitudinals in steel with light-alloy sections to complete the composite Construction. With 1-in.-thick boards laid in the steel floor angles and its 9.00 by 20-in. tyre equipment. the. Sentinel has a floor height of 3 ft. 1 in. when laden.

The Sentinel horizontal power unit is a proved engine well beyond the teething-trouble stage. Modifications' made since the original design was • evolved include hardened gears to drive the transversely mounted fuel pump, . which is supported at the front of the crankcase casting, and chrome-iron liners which replace the former chromium plated bores. The upper two rings of each piston are riovv chromium plated. .

Employing the Ricardo Comet Mark III combustion system, the unit is Britain's sole representative of indirect injection in the heavy class-of-engines used for road tiansport. Theoretically, the pre-combustion engine is at a slight disadvantage when compared with direct-injection units, in respect of the fuel consumption rate and the need for cold-starting equipment, but these are counterbalanced by the advantages of wider torque range, improved coinbustion characteristics at high speed, and less noise.

The smoothness of the Sentinel six cylindered unit is further improved by the method of mount

ing it in the chaSsis. This mounting employs three Metalastilc rubberbonded pads at the front Of the cylinder block, these being so positioned between the engine and supporting frame that radial lines passing through their centres meet at a common predetermined focal point At the rear, there are, two inclined rubber bonded pads in which the radial lines passing through their centres also meet at a predetermined point. The line passing through these two focal points forms the axis of oscillation of the engine mass, the rubber pads allowing movement of the mass to absorb the majority of the disturbing forces. Additionally, a radial arm restrains fore and aft movement, and snubber buffers are fitted to restrict excessive torque reaction during sudden acceleration or braking.

The radiator, which is carried between theframe side members immediately behind the front crossmember, comes partially above floor level, but does not obtrude into the body. A one-piece shaft, adjustable on its splines for length and equipped with Layrub joints, carries the drive to the fan which operates at crankshaft speed. The fan is carried on a spider outrigger attached to the radiator cowl, and incorporates a spring clutch drive. On the test chassis the fan was a five-bladed steel pressing, but there is available a ninebladed Aerofoil fan for exceptional conditions, such as obtain in hot countries or extremely hilly areas.

The power unit is fitted in the chassis with the crankshaft offset to the centre line of the frame, which brings the cylinder heads immediately below the right-hand side member with the injectors tucked away just clear of the channel. Removal of the injectors would, in my opinion, be preferable via the floor trap in the body,. a feature which will have greater significance at a later period in the life of the power unit when the injector feed pipes will probably be misshapen.

The starter motor, which is mounted on top of the engine, can be reached from the floor trap, together /41 with the Clayton Dewandre exhauster which is belt-driven from the front of the crankshaft. The dynamo, mounted forward with the radiator, shares the drive from the crankshaft extension.

A Borg and Beck 16-in.-diameter clutch with spring-type centre plate, conveys the drive to a four-speed gearbox, which is secured to the rear of the engine. Spur gears with sliding engagement are used for the two lowest ratios, whilst third gear and direct drive employ constant-mesh single-helical gears with dog-clutch operation. There is a three-piece selector tube between the gear lever and box, and a relay attached to the gear case forms the final link to the selector fingers.

Like other models in the Sentinel range, the passenger vehicle has an axle with central overhead worm drive, the axle case being a one-piece drop forging. The long semi-elliptic springs; at both axles, are assisted by Woodhead Munroe 2-in.-diameter hydraulic shock absorbers.. Clayton Dewandre triple-servo braking is specified for this model, the main servo-motor, with a 7-in.-diameter unit; operating the rear-brake camshafts through rods and levers: the front brakes are actuated by individual servo cylinders.

The test vehicle was loaded in readiness for the road, the allowance of 3l tons for passengers and baggage being rather generous. Complete with a standard bus body, made at Shrewsbury, the Sentinel is registered at 6 tons 18 cwt. unladen. Apart from a short run after assembly, there was little mileage to the credit of the Sentinel, so I planned a trip to Dolgelley, to remove some of the initial stiffness.

Never Again!

Driving through Shrewsbury during the early peak period, was no mean task with a full-sized singledecker chassis, and it was an experience that I would not care to have with a complete vehicle. This is not intended to be a reflection on the vehicle under test, which handled extremely well, but the lack of traffic control in Shrewsbury does provide difficulties for the driver of any heavy commercial vehicle.

I was agreeably surprised at the quietness of the power unit, but this is one of the . advantages of the indirect-injection engine. In theory, a four-speed gearbox and a big engine form a correct combination in a bus chassis, but for town driving I would prefer the extra gears, as supplied in the Sentinel goods models. This is a personal preference which, although of advantage to the driver, might affect economy.

The chassis was driven at a moderate speed out to Welshpool and across the border to Dinas Mawddwy, where a stop was made at a fork before starting the severe climb over the Bwlch-Oerddrws Pass. It was here that I committed the mistake of trying an alternative route, which, at the start, appeared more difficult. The right-hand fork was signposted as a severe climb to Bala with rough surface conditions. I soon realised that this was no fit road for a large vehicle, because there was little room to pass oncoming traffic, apart from the menace of overhanging trees.

In payment for my mistake I had to drive for what seemed an interminable period before finding a convenient .turning point, the road being flanked by banks and ditches.. During this time the Sentinel was called upon to make numerous getaways from rest on steep gradients, but its conduct under all difficulties

was in keeping with the standards of all Shrewsbury-built models. I was much relieved when a turning point was found and I subsequently reached the main road without coming to harm.

Then came the planned climb over the Pass which, according to the local surveyor, is a mile long with an average gradient of 1 in 7. DinasMawddwy is noted for causing elevated water temperatures, and the Sentinel fell a victim almost as the summit was reached. With an atmospheric temperature of 75 degrees F., together with a light following breeze arid plenty of low-gear work, including four minutes in bottom gear, the conditions were favourable to a boiling radiator. The Sentinel succumbed to boiling just as I was slowing up in readiness for a stop-start trial on a 1-in-5 gradient, but had the nine-bladed fan been fitted the water temperature would not have reached the boiling point. -The engine-oil temperature at this juncture was 182 degrees F.

1%-mile Climb

After waiting for the water to cool, the test was resumed and the start from rest accomplished without difficulty. The turning point was Dolgelley, after which we were again faced with the climb over the Pass, but in the reverse direction. The gradient on the return was longer but less severe, and in 1 miles of continuous climbing the radiator water reached a maximum temperature of 180 degrees F.

The works driver took over at the crest of the Pass and promptly proceeded to demonstrate the capabilities of the vehicle while I endeavoured to retain a seat on the payload. With little to hold on to during fast cornering or 'drastic braking, my position was rather precarious. Undoubtedly, 16-stone " plus " of driver behind the wheel made some difference, and we reached Shrewsbury after covering 58 miles in 2 hrs. 5 mins.

Although the Dolgelley trip had added 100 miles to the run, there was no noticeable difference in the initial tightness of the chassis. There was, for example, a certain heaviness in the steering and gear-selector operation, the latter requiring a little skill to avoid over-running the neutral position when changing gear. This made a slight difference to the acceleration times, the tests being made using first, second and third gears to reach 30 m.p.h., and engaging direct drive immediately afterwards. The Sentinel required 26.5 secs. to reach 30 m.p.h. and a further 27.5 secs. to accelerate to 40 m.p.h.

The Clayton Dewandre . tripleservo braking system behaved consistently, and in all trials the stopping distance did not vary by more than 3 ft. when braking either from 20 or 30 m.p.h. There was a slight timedelay in the system, but the ultimate retardation—the Tapley meter showed 58-63 per cent—would not cause difficulties to standing passengers. Measured by the pistol method, the chassis was stopped in 71 ft. from 30 m.p.h. and 31 ft. from 20 m.p.h.

Then followed the fuel-consumption trials, carried out over a circuit chosen to balance out any variation of gradients. The first trial was made on the A41 road between Hadnall and Whitchurch, the turning point being approximately 10 miles from the start. There were minor gradients which required full injection in top gear, but to a lower. powered machine this might have called for a change in ratio. During the coach-service test there was a single stop in each direction and little hindrance from other traffic, therefore the average speed was high for a short run. The consumption rate of 11.5 m.p.g. is slightly below, the average, but the pumping losses in a new engine of large capacity, coupled with the initial tightness of the chassis as a whole, would have an adverse effect on the fuel-consumption return.

It is only during peak hours that buses are loaded to maximum capacity, so that the results obtained with a full load all the time might be improved upon in normal service. The Sentinel high-speed pre-combustion oil engine has exceptional power, and for bus work some users have specified a lower, governed engine speed. The economy under such conditions might be rather more favourable.

Suburban Service

During the 20-mile test, with one stop per mile, slightly over 2 gallons of fuel were used, and this is equal to 9.7 m.p.g. On the four-stops-permile circuit, the consumption rate worked out at 7.5 m.p.g. As this chassis had the normal fuelpump-governor setting, the period spent in the indirect-gear ratios during stage work was relatively short despite a high-ratio axle.

The brakes took all the punishment I could give them when making 40 stops in 10 miles, the route being shortened for this particular trial. As a finale, I made a hand-brake test with hot drums. By the stop-watch method the stopping distance from 20 m.p.h. was 66 ft., a result which was confirmed by the Tapley reading of 22 per cent. The capacity of the hand brake is ample to satisfy the local Ministry of Transport certifying officers Judged by the high initial friction recorded in the test chassis, the economy of the Sentinel would be improved with further operation and the controls would be easier to manipulate.