by Tony Wilding MIMechE. MIRTE

Page 44

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

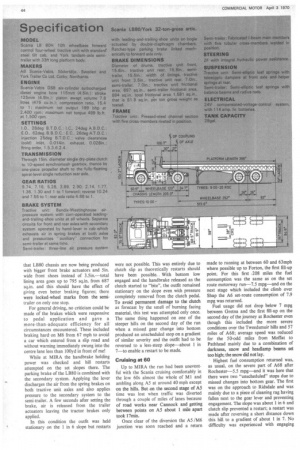

AN OPERATIONAL-TRIAL fuel consumption 1 mpg better than any other 32-ton-gross artic previously tested and at a better average speed shows the Scania LB80 to be a worthwhile vehicle to operate. Add to this extremely easy handling, a comfortable cab and a low level of engine noise and you have what must be one of the more acceptable vehicles available on this country for operation at this weight.

At times there was a feeling that the Scania was only average on performance, but in fact, this feeling was completely the wrong impression and more than likely due to the level of cab noise being so very low. Even when cruising on motorways at 60+ mph and over, normal conversation was possible and the cab radio could be enjoyed on a relatively low volume-control setting. On comparing the point-to-point average speeds on the 732-mile long operational trial with those of other vehicles and then the final overall average of 36.35 mph it is apparent that the LB80 is among the best.

I cannot recall having driven a truck with better steering and except for a rather heavy engagement action when selecting the lower three ratios in the synchromesh gearbox, driving the Scania was no more arduous than driving a car.

Acceleration times were above the average for 32-ton-gross attics but braking figures were slightly worse than average. Normal braking was more than adequate and there should be even an improvement with current chassis as bigger front brakes are now being fitted on production to the model. On some road surfaces the front springs seemed a little hard but the overall suspension design was very good. The Scania LB80 used was loaned for the tests by Brain Haulage, of Grays, Essex, being one that this company operates on contract to Associated Container Transport Ltd. It was coupled to a York tandem-axle demonstrator loaded with 21 tons 14.5 cwt of concrete blocks which brought the gross combination weight with three men in the cab to 7cwt short of the 32-ton figure.

The LBO was introduced almost exactly one year ago and mechanically is based on the L80 normal-control chassis. Either the naturally-aspirated D8, 155 bhp net diesel or the DS8 199 blip net turbocharged power unit are used in the model with the latter being standard in the tractive unit version as tested. The drive is taken through a 15in. single-plate clutch to a 10-speed synchromesh transmission consisting of a five-speed main section and two-speed planetary splitter gearing. The cab for the model was completely new and while following the general lines.

and standard of construction of the 110

which is designed for higher gross weights it is more compact and provides seats for only two men. The cab tilts forward 60deg using a hydraulic pump and ram system. Originally the LB80 was rated for a maximum of 30 tons but since then the limit has been increased to the 32-ton figure.

Fuel consumption On the day before the start of the operational trial, set-route fuel consumption tests were made on A6 and MI south of Luton to allow comparisons to be made with vehicles tested before CM started long-distance tests on heavier vehicles over the regular route to Scotland and back. On these the LB80 returned figures which were better than. any *previously recorded on a maximum-weight artic and they set the pattern forrn the results achieved on the 732-mile two-day journey; this was one mile longer than normal because of a diversion on A5.

The operational trial began against a background of snow and with forecasts of bad weather. The forecasters turned out to be wrong and the snow expected did not materialize. But there was a good deal of rain on the second leg (running south) which produced difficult conditions. A break was made in the run on the first day in order to do brake and acceleration tests at the Motor Industry Research Association test ground at Nuneaton. The road surface used for braking was clear of snow and dry but on all the maximum pressure stops there was locking of the driving axle wheels—by as much as 40ft on one stop from 30 mph. This obviously detracted from the figures and suggested that more effort could be applied to tilt front brakes; there were no marks at all from these tyres. After the test I leaniec

that LB80 chassis are now being produced with bigger front brake actuators and Sin. wide front shoes instead of 3.5in.—total lining area goes up to 795 sq.in. from 687 sq.in. and this should have the effect of giving even better braking figures: there were locked-wheel marks from the semitrailer on only one stop.

For general driving, no criticism could be made of the brakes which were responsive to pedal application and gave a more-than-adequate efficiency for all circumstances encountered. These included braking hard on M6 from 67 mph to avoid a car which entered from a slip road and without warning immediately swung into the centre lane less than 100yd in front of me!

While at MIRA the handbrake holding power was checked and hill restarts attempted on the set slopes there. The parking brake of the LB80 is combined with the secondary system. Applying the lever discharges the air from the spring brakes on both tractive unit axles and also applies pressure to the secondary system to the semi-trailer. A few seconds after setting the brake, air is released from the trailer actuators leaving the tractor brakes only applied.

In this condition the outfit was held stationary on the 1 in 6 slope but restarts were not possible. This was entirely due to clutch slip as theoretically restarts should have been possible. With bottom low engaged and the handbrake released as the clutch started to "bite", the outfit remained stationary on the slope even with pressure completely removed from the clutch pedal. To avoid permanent damage to the clutch as forecast by the smell of burning facing material, this test was attempted only once. The same thing happened on one of the steeper hills on the second day of the run when a missed gear change into bottom produced an unscheduled stop on a gradient of similar severity and the outfit had to be reversed to a less-steep slope—about l in 7—to enable a restart to be made.

Cruising at 60

Up to MIRA the run had been uneventful with the Scania cruising comfortably in the low 60s almost the whole of MI and ambling along AS at around 40 mph except on the hills. But on the second stage of AS time was lost when traffic was diverted through a couple of miles of lanes because of road works near Cannock and getting between points on AS about 1 mile apart took 17min.

Once clear of the diversion the A5 /M6 junction was soon reached and a return made to running at between 60 and 63mph where possible up to Forton, the first fill-up point. For this first .208 miles the fuel consumption was the same as on the set route motorway run-7.5 mpg—and on the next stage which included the climb over Shap the A6 set-route consumption of 7.9 mpg was returned.

Fuel usage did not drop below 7 mpg between Gretna and the first fill-up on the second day of the journey at Rochester even though this included the more severe conditions over the Tweedsmuir hills and 57 miles of A68; average speed was reduced for the 50-odd miles from Moffat to Pathhead mainly due to a combination of darkness, snow and headlamp beams set too high; the snow did not lay.

Highest fuel consumption returned was, as usual, on the severe part of A68 after Rochester-5.5 mpg—and it was here that there were two "unscheduled" stops due to missed changes into bottom gear. The first was on the approach to Ridsdale and was mainly due to a piece of cleaning rag having fallen next to the gear lever and preventing engagement. The slope was about 1 in 6 and clutch slip prevented a restart; a restart was made after reversing a short distance down this hill to a gradient of about 1 in 7. No difficulty was experienced with engaging first on -the many occasions after this, including Riding Mill, but on Castleside where the 1 in 5.2 section is reached very soon after the start and a lot of quick left-hand work is required, the same thing happened again including a short reverse to allow restarts.

Also following the usual pattern, the best consumption was on A1-8.4 mpg. And for the final 150 miles of motorway where there was a strong wind coming from the offside front corner, as well as heavy rain and vast amounts of spray which made driving difficult, the consumption was just over 7 mpg.

During the operational trial, times for the climbs of the most severe hills on the route—Shap, Carter Bar, Riding Mill and Castleside—were taken. In the case of Shap there was some baulking by other traffic but the 4.25 miles from the Jungle Cafe to the top was completed in the reasonable time of 1 lmin 28sec. Minimum speed on the climb was 5mph—on the 1 in 9 section—and over the final stage where the average gradient is 1 in 11 /12, the road speed varied between 9 and 11mph. Minimum gear on the 1 in 9 section was second-low while second-high and third-low were used on the less-steep part. Road speed at the start was 15mph and at the end of the climb 26mph was indicated.

The 1.82-mile climb up Carter Bar was started at 40mph and took 6min 54sec. On the general gradient of 1 in 13/14, second-high was engaged with a road speed around 12 /13mph and this gear was just right up to the steepest (1 in 9) part where second-low was needed and the speed dropped to 5mph. At the top the speed was 14mph in second-high.

Riding Mill is a shorter hill but the

steepest on the route with a maximum gradient of 1 in 5. Soon after the turn onto the hill, first-high was engaged and held for a good part of the climb until a change to bottom-low was needed. At this point road speed dropped to almost nil but then engine speed quickly built up to bring the vehicle to its maximum in the gear of 4 mph. After a climb that had taken a total of 4min 25see, road speed had reached 8 mph in second

As already mentioned, Castleside was one of the hills where difficulty in restarting was experienced. This happened on the 1 in 5.2 gradient about 200yd from the bottom. It had taken 25sec to reach this point after starting the climb at 40 mph. After the restart 6min 30sec were needed to reach the top making a total of 6min 55sec for the 0.8-mile climb, speed at the top being .15 mph.

Without the delays on A5 on the first day, the total journey of 732 miles should have been completed in just about 20hr. As it was this figure was exceeded by Ilmin to give an average speed of 36.35 mph. And with just over 100gal of fuel used for a return of 7.3 mpg, the commendable time-load-mileage factor of 8,397 resulted. Comparing the operational trial with others in the 30/32-ton class, the fuel consumption has only been bettered by one artic and the average speed by a second, both of which were tested at 30 tons gross.

After the run I was less tired than I had been after most other operational trials that I have carried out and in my opinion this was mainly due to the low level of noise in the cab and the easy handling characteristics of the LB 80. I cannot recall ever having driven a quieter heavy vehicle and certainly I have not come across one with better steering. Not only was little effort required but there was adequate "feel", so that there was no tendency to over-correct when making small adjustments in direction. There was no tendency for the outfit to wander or move from the chosen fine even on very uneven surfaces which suggests that the geometry and suspension design is near perfect. I am prepared to accept the slight suspension harshness apparent on some road surfaces to retain these good points.

The clutch and brake pedals and accelerator Were light and conveniently placed. But like the heavier Scania models that I have tested care had to be taken when engaging the clutch starting from rest. This was really only when first taking over the driving seat and even then there was much less "bucking", than I had found it possible to induce on the old L876.

Gear engagement of heavy-vehicle synchromesh gearboxes is generally heavier than on constant-mesh units. On the LB80 selecting top and fourth gears was straightforward and did not need too much effort provided attempts were not made to engage the ratio too quickly. But, although easier after use. engagement of the three lower ratios was always more difficult. The "baulking" was heavy and the main problem I had was that there was no clearly defined "slot" into which the lever had to go.

The brakes were responsive and there was more than adequate retardation for normal driving and as I have said, driving the Scania was not much more arduous than driving a car. This feeling was enhanced by the standard of cab fitting and finish and an excellent heating system. The test was completed in temperatures only a little above freezing point and although there were a couple of small draughts in the panel below the facia, these were easily overcome by the amount of heat coming from the system, even on a setting well below the maximum.

All-round visibility was very good and almost the whole screen was cleared by the wipers; there was a small triangular unwiped area on the driver's side which could be eliminated by a slight increase in the "set" of the arm.

A lot of thought has been put into accessibility for maintenance by the designers of the LB80. In the cab, easily removed panels on the dash at both sides provide access to electrical items such as fuses and wiring connections. When the cab is tilted to its full 60deg any part of the engine can be easily reached. A hydraulic pump is operated to raise and lower the cab and this calls for more effort than the more common manually tilted design, but daily attention such as water and oil checks can be made by raising the hinged grille on the front. When down, the cab is securely held by two over-centre locks at the rear as well as an internal locking system and the hydraulic system also provides holdingdown effort.

At a basic chassis /cab price for the LB80 tractive unit of £4,260 the model seems to me to represent very good value for money; a view which I am sure will be shared by both operator and driver.