Rear Axles at Olympia.

Page 6

Page 7

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By a Chief Draughtsman.

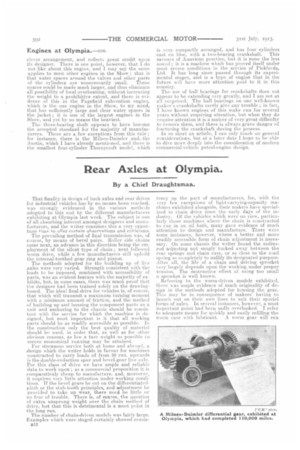

That finality in design of ,back axles and rear drives for industrial vehicles has by no means been reached, was strongly evidenced in the various methods adopted to this end by the different manufacturers exhibiting at Olympia last week. The subject is one of all absorbing interest amongst ,designers and manufacturers, and the writer considers this a very opportune time to offer eertain ohsereations and criticisms.

The prevailing method of final transmission was, of course, by means of bevel pairs. Roller side chains came next, an advance in this direction being the employment. of the silent type of chain ;. next followed WOrill drive, while a few manufaeturers still uphold the internal-toothed gear ring and pinion.

The methods adopted for the building up of live axles were very varied. Strength consistent with the loads to be imposed, combined with accessibility of parts, was an evident feature with the majority of ex hibits, but, in some eases, there was much proof that the designer had been trained solely on the drawinghoard. The ideal final drive for vehicles is, of Course, that which will transmit a maximum turning moment with a minimum amount of friction, and the method of building up and housing the component parts as a unit and anchoring to the chassis should be consistent with the service for winch the machine is designed, but most important is it that all working parts should be as readily accessible as possible. In the construction only the best quality of material should be used, in order that, as well as for other obvious reasons, as low a tare weight as possible to secure economical running may be attained.

For strenuous service both at home and abroad, a design which the writer holds in favour for machines constructed -to carry loads of from 30 cwt. upwards is the double-reduction spur and bevel-gear live axle. For this class of drive we have ample and reliable data to work upon as a commercial proposition it is comparatively cheap to manufacture, and, moreover, it requires very little attention under working conditions. If the bevel gears be cut on the differentiatedpitch or the stub-tooth principles, and adjustment be provided to take up wears there need be little (uno fear of trouble. There. is, of eonese, the question of extra unsprung weight over the chain method of drive, but that this is detrimental is a moot point in the long run.

The number of ehaindriven models was fairly large. Examples which were staged certainly showed consisB12

tency op the part of manufacturers, for, with the very few exceptions of light-carrying-capacity machines exhibited alongside, their makers have specialized in chain drive since the early days of the industry. Of the vehicles which were on view, particularly those machines eherc the chain is constructed to run in an oil bath, many gave evidence of much attention to design and manufacture. There were. some instances, however, where a better and more readily accessible form of chain adjustment is necessary. On some chassis the writer found the radiusrod adjusting nut snugly tucked away between the rear springs and chain case, or so close to the read spring as etenpletely to nullify its designated purpose. After all, the life of a chain and driving sprocket very largely depends upon the working under proper tension. The destructive effect of using too small a. sprocket is well known. Referring to the worm-driven models exhibited, there was ample evidence of much originality of design in the methods adopted for housing the gear. This .may be in consequence of makers' having to launch out on their own lines to suit their special forms of axles. In several instances, however, a most important point had been sadly overlooked. I refer to adequate means for quickly and easily refilling the worm case with lubricant. A worm gear will run Ignition at Olympia. By an Expert.

As a practical user of commercial-motor vehicles, and as one who has in the past suffered very consichne ably from small yet irritating ignition faults, the majority of which could well have been avoided by the adoption of satisfactory methods for the installation of the electrical kit, I was particularly pleased to have the opportunity to examine a large number of models and to contrast in my own mind the methods which the designers had adopted to ensure so far as possible the elimination of small ignition faults.

In particular was my attention drawn to the various methods which are employed by leading makers in respecc of the fixing of the altimportant magneto. Low-tension ignition or the battery-and-coil system call for no comment, as they are at this time of day nearly out-dated. The Albion is the notable and successful exception. In a good many instances I came to the conclusion that the designer only seemed to have remembered at the last moment that he had to embody a magneto in his engine arrangement, and he therefore set to work to plank this down in the first position which occurred to him. In many cases he certainly chose—inadvertently I trust—as inaccessible a position under the bonnet as possible.

On one well-known make of lorry I noticed that the Bosch magneto was fitted directly behind the radiator and just above the level of the bottom tank, thus being in an excellent position to collect any dust which will inevitably filter through the radiator. It is all very well to say that a modern magneto is practically dust-proof, but, even granted that the best makes are practically so, it is obviously foolish to throw dust at such a delicate piece of mechanism. This is an example of "asking for trouble."

On the Milnes-Daimler stand a Merdeles engine was exhibited with the magneto at the flywheel end ; this was easily accessible. The leads on this design were carried directly from the magneto through a pipe to the plugs. But the question which arose in my mind was, how to get number-three plug out without taking down an induction pipe and a tappet rod.

For examples of accessibility and simplicity in respect of ignition installa&ons I could not point in my mind to better examples than those which were shown on the Daimler and Napier stands. In both instances a Bosch magneto ia fitted on all the models, and on the latter it is placed in the centre of the engine, and held in position by a strap. This, of course, means that it is only necessary to undo one bolt in order to release the magneto. The leads in this example, too, are carried neatly through a tube to the plugs. In the case of the Daimler the magneto is carried by a bracket on the side of the base opposite cylinders numbers one and two, and is held to the bracket by a strap. An aluminium cover is provided, and this obviously is destined to prolong the life of the dynamo. The leads in this case are coloured, and are carried through tubing to the various plugs. This results in considerable simplification for the ordinary driver, and there is very little chance of his replacing one incorrectly.

The next installation which caught my eye, and the name of the machine on which it was found I will considerately omit., included a tangled mass of lead insulated wires, which reminded me more than anything of the back of a telephone exchange board.

In respect of switches, these, generally speaking, seem to have been forgotten ; in my opinion, they are most important. The driver must. be considered. He is often a man who would not think for himself, and I have come across numerous eases of drivers' leaving their engines running, and when they have been asked their reason for so doing, I have been informed that there was no switch. Such a thing as disconnecting a lead or shorting a plug has never entered their heads. A suggestion has been made to me that a useful development is the suitable inter-connection of

switch and throttle : an example of this was to be seen on one of the French models at the Show.

I consider that .leads should always be coloured, and they should run through fibre tubing fitted with suitable aluminium T or elbow pieces, as is found convenient. The magneto itself should never be pat on us if it were an afterthought. It should be placed in the most accessible position possible.

Shall I be accused of partisanship if, in conclusion, i write that. I am impressed with the constant-break arrangement and other characteristics of the Men magneto which was shown in the gallery.

Gearboxes at Olympia.—By C. M. Linley.

It is strange that such an important unit as the gearbox should_ have undergone so little change since the last. Commercial-Vehicle Show, The most noticeable feature in this respect at Olympia was that there seems nowadays to be little, desire on the part of designers to depart from standard practice. Generally speaking, there was nothing new at the Show in gearboxes. There are not. even the freak gearboxes which one generally looks for at motor-vehicle exhibitions.

It is evident that there is still a great difference of opinion as to which of the standard types is the most suitable for commercial vehicles. A fair number of firms shows sliding gears, whilst others pin their faith to the dog or internal-engagement type. It is ceriom that. designers have not fallen more into line. FICHE an examination of the more recent designs shown. I should say that three speeds will only be used on light types, and that all models carrying over two tons of load will in the future have four speeds.

One interesting tendency is that towards fitting the gear-control levers inside the gearbox instead of outside. Many firms show both types, but inside levers were mostly to be found on the more-recently. designed models. On the heavier types, bearings in the centre c f the gear shafts seem to have been found necessary, and represent the latest practice. Ball bearings in gearboxes seem to be almost universal, the Argyll being a noticeable exception. In this model the wise precaution has been taken of fitting fine gauze strainers over the oil inlets to the bearings, so as to exclude chips.

I was surprised to see that the apparently excellent design of the Argyll box, whereby the whole top could be taken off and all the internal parts removed, has been abandoned.

Splined shafts have almost entirely taken the place of square ones. The chain gearbox does not seem to have been adopted by any but its originators. The gearbox shown on the Minerva is a particularly neat one, but, only having three speeds, seems out of keeping with the very massive construction of the rest of the chassis.

The Maudslay works show a good example of British design_ The Comities still has its woll-tried patent gearbox which it has fitted for so many years. On the Austin and the Stoneleigh there is a return to the old practice of fitting the change-speed lever in the centre of the car instead of at one, side. The hitter of these vehicles is one of the few departures from standard practice in the Show. In this chassis the gearbox is made of a steel casting and is fixed to, and formsthe front part of the torque tube. This arrangement gives the chassis a very clean appearance and cuts out one of the universal joints.

The fact that so little alteration has taken place in gearboxes must not be ta-ken as a sign of want of attention to this part, but should rather point to the fact that tile present design, although admittedly not perfect, is evidently doing its work very well and that no immediate change in this part is nrgertly needed.