HOPS HAULAGE MONEY-MAKER

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

CONDITIONS in the hopfields have changed considerably of late— and so have those relating to.the transport of hops. The dwindling number of oasthouses still used for their original purpose, evinced so clearly by their growing popularity as roadhouses and tea shops, is the outward and visible sign of an

inward shrinkage, which, however, is not altogether to be deplored from an economic aspect.

Time Was when every farmer in Kent, as well as many in Worcestershire and Hampshire, every smallholder even, grew hops almost to the capacity of his holding. The number of growers has diminished and the acreage now under hops is but a tithe of what it used to be.

That is, in part, the result of Government control and limitation of output. It is also—and, perhaps, to a greater extent—the result of the application of modern cultural science to the farming industry. In the old days hops were grown in much larger quantities, but a considerable percentage was of poor quality or diseased, and was not even picked, let alone dried and prepared for market.

To-day, the hop grower, by careful selection of the plant, by assiduous care during growth, by spraying and the use of other modern methods of dealing with disease, ensures that most of the hops which he grows are sound and find their way to the brewer.

Some indication of the change can be ,gathered from price fluctuations. There was a time when the best price that could be obtained was 45s. per cwt. In 1920, £18 per cwt, was obtained. To-day, £9 per cwt. is a fair average price, rising to Ell for exceptional quality hops and falling to 26 or £7 for produce which is not quite up to standard.

Again, moderniza tion of drying methods is tending to reduce the need for 50 per cent. of the oasts which were required up to so recently as three or four years ago. Until comparatively recently the hops were dried, as it were, in the chimney of the fire. The floor of the oast, a fine mesh net on which the green hops were laid, was actually over the furnace and the fumes from the fire passed through the hops and so dried them.

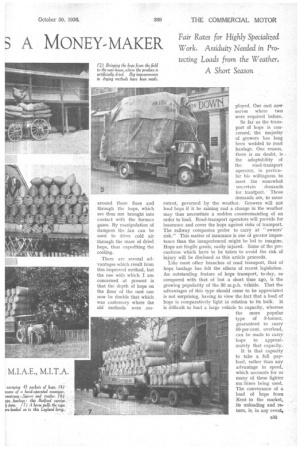

To-day, in the up-todate oast-houses, that practice has ceased. The flues of the furnace are enclosed. A fan drives air around those flues and through the hops, which are thus not brought into contact with the furnace gases. By manipulation of dampers the fan can be used to drive cold air through the mass of dried hops, thus expediting the cooling.

There are several advantages which result from this improved method, but the one with which I am concerned at ptesent is that the depth of hops on the floor of the oast can now be double that which was customary where the old methods were em ployed. One oast now serves where two were required before.

Sc) far as the transport of hops is concerned, the majority of growers has long been wedded to road haulage. One reason, there is no doubt, is the adaptability of

the road-transport operator, in particular his willingness to meet the somewhat uncertain demands for tran8port. • Those demands arc, to some extent, governed 'by the weather. Growers will not load hops if it be raining and a change in the weather may thus necessitate a sudden countermanding of an order to load. Road-transport operators will provide for insurance and cover the hops against risks of transport. The railway companies prefer to carry at "owners' risk." This matter of insurance is one of greater importance than the inexperienced might be led to imagine. Hops are fragile goods, easily injured. Some of the precautions which have to be taken to avoid the risk of injury will be disclosed as this article proceeds.

Like most other branches of road transport, that of hops haulage has felt the effects of recent legislation. An outstanding feature of hops transport, to-day, as compared with that of but a short time ago, is the growing popularity of the 30 m.p.h. Vehicle. That the advantages of this type should come to be appreciated is not surprising, having in view the fact that a load of hops is comparatively light in relation to its bulk, it is difficult to load a .large vehicle to capacity, whereas the more popular type of 3-tonner, guaranteed to carry 50-per-cent. overload, can be made to carry hops to approximately that capacity.

It is that capacity to take a full payload, rather than any advantage in speed, which accounts for so many of these lighter ma innes being used. The conveyance of a load of hops from Kent to the market,. its unloading and return, is in any event,

a day's work. It can, provided that there is not too much delay at the unloading end, be accomplished within the specified working hours for a driver, although the vehicle is legally limited to 20 m.p.h.

From the point of view of the road haulier, the outstanding disadvantage of hops transport is the brief season, which extends only to three weeks. At least, that is the Case so far as the bulk of the loadings is concerned.

It is usually the case that a few loads are available during the fourth week, but the quantity then to be carried is comparatively small. Ahaulier who has fairly regular work for his vehicles all the year round, will not, perhaps, find much attraction in this class of work.

Another point to bear in mind is that some considerable knowledge, skill and experience are necessary in the loading of hops. Those who have not yet had any experience of this class of. work will find the accompanying illustrations helpful.

Hops are packed in what are called pockets. These are about 7 ft. long and 2 ft. in diameter. Each pocket weighs 11 cwt. A load of hops can, therefore, be 12-14 ft. above the platform level of the vehicle. The loading is peculiar, too. At a casual glance it would appear as though some of the pockets were in danger of tumbling off. Actually, of course, there is no such risk.

Those pockets which appear to be ready to fall are, in actual fact, roped to the others and, to some extent, serve as anchorages for the row of ,pockets above. It is in this building up and roping of the layers of pockets, one above the other, that so much skill and experience are necessary.

The first layer comprises pockets, some of which are laid transversely on the vehicle and others—invariably those at the rear of the lorry—longitudinally. Those laid lengthwise at the rear form a substantial support for the second layer, which is held by ropes to the first layer.

The hops are put into the pockets under great pressure. The pockets themselves are substantially made sacks, each costing Gs. or 7s., and new pockets are essential for every load. They must be perfectly clean when they reach the warehouse. So important is this point that some farmers insiston the lorry driver and packer changing their shoes before they proceed to load. This is necessary because they must stand on the pockets as they build up the edifice which is exemplified in the illustrations.

In fine weather, the haulage contractor who carries hops is relieved of a good deal of responsibility. In poor or changeable weather he must take great care of his load. If it appears likely to rain in the course of a journey, that contingency must be guarded against. It is usual then to protect the hops by tarpaulins in at least two layers. These tarpaulins are expensive, averaging about £12 each, and after two seasons new ones are required. The old ones may still suffice as under covers, but they should not on any account be used for the outer protection.

Care is needed on the road. Only good hard roads can be traversed without risk. If the road be not so good or soft at the sides, the driver must be particularly careful, because, owing to the extreme height of the load and its tendency to swing, there is a risk of the vehicle overturning. Another point of importance is that the route selected must be entirely free from low bridges.

But if the risks and responsibilities be great, the remuneration is, to some extent, commensurate. The facts that it is a specialized branch of haulage and that there are not too many operators in a position to cater for it are, perhaps, factors in maintaining rates at a reasonable level.

It is usual to provide for " all-risks " insurance of the hops in transit, that covering the possibility of damage by rain, as well as the normal dangers of fire, collision and so on. This insurance costs approximately 3d. per pocket. A rate which was paid during the past season for hops transport was 2s. 3d. per pocket, inclusive, leaving a net figure for the haulier of 2s. per pocket.

The average 3-ton lorry will carry 40-45 pockets,

bringing a revenue of 24-£4 10s. per day. During the brief season, if the weather be at all favourable, the vehicle may make five journeys per week, covering approximately 600 miles: The revenue is 9d. per mile run, which shows a fair profit.

Similarly, a rigid six-wheeled 10-tonner can carry 80 pockets and, on that basis, brings a revenue of Is. 4d. per mile run. Only one load is possible per day and there is rarely time to pick up a return load, even when one is available.

The work is profitable so long as the haulier's organization is such that, in the event of a sudden postponement of a load, as described above, he can turn to other work and is not obliged to keep his vehicle idle for a day.

The quantities available vary somewhat from year to year, but are nowadays almost stabilized at about 12,000-14,000 tons per season. The principal centre is the Paddock Wood region -f Kent, which is at the western end of that county, but there are fair loads available practically throughout Kent, some in certain parts of Hampshire and some, again, in Worcestershire.