From the Drawing 13pari

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Graham Montgomeric

UEL availability and prices ave regularly made headline ews during recent years and, iith an urgency sometimes aproaching panic, the search for lternative fuels to conventional etrol and diesel goes on ?.morselessly.

Some operators are using liuefied petroleum gas, but lese are conversions of petrol ngines whether it is a Ford enme for a Cortina or a Rolls-' :oyce engine for a Leyland Clyesdale.

One engineer extremely inN-ested in the use of log is

■ ickie Duncalfe of RHM Foods td. The difference is that he is sing lpg in conjunction with liesel.

The idea behind the lpg/diesel iroject came about purely by hance. RHM is a large 'user of eet cars and some of these ortinas) were scheduled to be onverted to run on lpg by Landi lartog (UK) Ltd — formerly 'orkshire Autogas.

In the course of conversation Duncalfe asked if it was posible to run a diesel engine on las, the reply being in the negaive along the lines of "you'd ilow the ... head off!"

But the germ of the idea had leen sewn with the result that he RHM experiment uses a nixture of 35 per cent gas and 65 per cent derv.

Although lpg is 15 per cent lower in calorific value than diesel, this loss is considerably reduced when a two to one mixture (approximately) is used, as in this case.

The other disadvantage is that the subsequent alteration to the derv's cetane rating makes starting on the mixture very difficult.

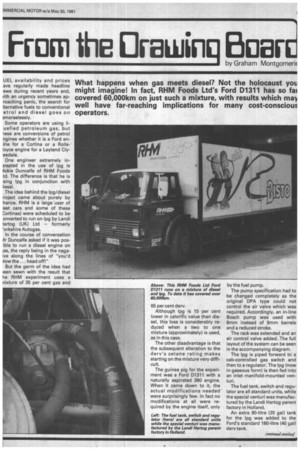

The guinea pig for the experiment was a Ford D1311 with a naturally aspirated 380 engine. When it came down to it, the actual modifications needed were surprisingly few. In fact no modifications at all were required by the engine itself, only by the fuel pump.

The pump specification had to be changed completely as the original DPA type could not control the air valve which was required. Accordingly, an in-line Bosch pump was used with 8mm instead of 9mm barrels and a reduced stroke.

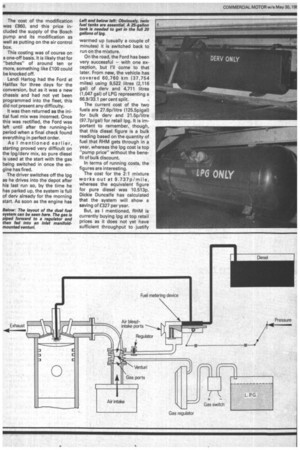

The rack was extended and an air control valve added. The full layout of the system can be seen in the accompanying diagram.

The lpg is piped forward to a cab-controlled gas switch and then to a regulator. The lpg (now in gaseous form) is then fed into an inlet manifold-mounted venturi.

The fuel tank, switch and regulator are all standard units, while the special venturi was manufactured by the Landi Hartog parent factory in Holland.

An extra 90-litre (20 gal) tank for the lpg was added to the Ford's standard 180-litre (40 gal) dery tank. The cost of the modification was £860, and this price included the supply of the Bosch pump and its modification as well as putting on the air control box.

This costing was of course on a one-off basis. It is likely that for "batches" of around ten or more, something like £100 could be knocked off.

Landi Hartog had the Ford at Halifax for three days for the conversion, but as it was a new chassis and had not yet been programmed into the fleet, this did not present any difficulty.

It was then returned as the initial fuel mix was incorrect. Once this was rectified, the Ford was left until after the running-in period when a final check found everything in perfect order.

As I mentioned earlier, starting proved very difficult on the lpg/derv mix, so pure diesel is used at the start with the gas being switched in once the engine has fired.

The driver switches off the lpg as he drives into the depot after his last run so, by the time he has parked up, the system is full of dery already for the morning start. As soon as the engine has .warmed up (usually a couple of minutes) it is switched back to run on the mixture.

On the road, the Ford has been very successful — with one exception, but I'll come to that later. From new, the vehicle has covered 60,760 km (37,754 miles) using 9,522 litres (2,116 gal) of dery and 4,711 litres (1,047 gal) of LPG representing a 66.9/33.1 per cent split.

The current cost of the two fuels are 27.6p/litre (125.5p)gal) for bulk dery and 21.5p/litre (97.7p/gal) for retail lpg. It is important to remember, though, that this diesel figure is a bulk reading based on the quantity of fuel that RHM gets through in a year, whereas the lpg cost is top "pump price" without the benefit of bulk discount.

In terms of running costs, the figures are interesting.

The cost for the 2:1 mixture works out at 9.7 3 7 p/mile, whereas the equivalent figure for pure diesel was 10.513p. Dickie Duncalfe has calculated that the system will show a saving of £327 per year.

But, as I mentioned, RHM is currently buying lpg at top retail prices as it does not yet have sufficient throughput to justify buying in bulk. If an estimated bulk price for lpg is substituted, then the fuel cost savings become significantly greater.

One extra benefit hoped for was in long-term cleanliness of the engine. When first spoke to Dickie Duncalfe about the project, the Ford had covered just over 31,000 km and Dickie commented that he was "loth to do more at this stage. I don't want to disturb the engine at the moment."

As it happened, the engine was disturbed for him.

Number two cylinder liner cracked, but Ford and RHM were perfectly happy that the failure was nothing to do with the log conversion, so the offending unit was replaced with _ashort engine under full manufacturer's warranty.

But the failure did present the opportunity for an internal engine inspection. As expected the engine was far cleaner than an equivalent diesel unit.

The cylinder head and valves had almost no carbon deposits, to the extent that with a quick "wipe over" it could be put straight back on to the new engine. There was no measureable bore wear.

I had a chance to drive the RHM vehicle resplendent in its Bisto livery and can report that under normal driving conditions there was very little to distinguish it from a conventionally fuelled machine.

The gas was switched on or off by means of a tumbler switch mounted to the right of the tachograph, and if this was operated to knock off the gas leaving the vehicle running on pure dery {but only at two thirds of normal delivery), then the change in performance was very noticeable.

Hardly surprising perhaps. As the regular driver put it "it turns into a slightly sedate sort of model."

From the driver's seat, I noticed a distinct difference in noise level when operating on the mixture — another point in its favour.

Dickie Duncalfe remains enthusiastic about the project, but he feels that operators should be given a bit of help in cases like this. At the moment, taxation on lpg has followed the base fuel rate pro rata.

As 50 per cent of RHM loads consists of bulk flour, Dickie feels that a rebate would be appropriate.

"If, as operators, we start an idea that works, we should have manufacturer and government encouragement. Bus companies get rebates so why can't food people and other essential ser vices?" he asked. • He reckons that if an operator can get fuel cost savings to balance a twoto three-year pay off, then the dervilpg system becomes economic. Anything over this and it doesn't make as much sense.

As far as Dickie is concerned, his vehicle is on the break-even point now, "If I can run it at the same level for a further 12 months, I will look at carrying out further conversions."

Even at top price for lpg, the fuel cost is the right side of the line with the bonus of a cleaner engine thrown in for good measure.