Trucking on the

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

front line

How different is a military logistics operation in Afghanistan from one back here in the UK?

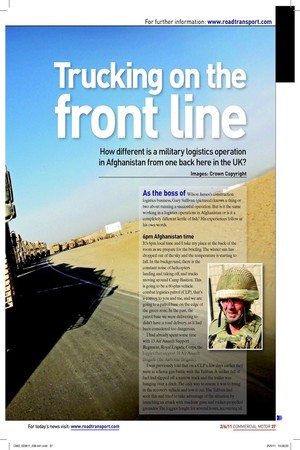

Images: Crown Copyright As the boss of Wilson James’s construction logistics business, Gary Sullivan (pictured) knows a thing or two about running a successful operation. But is it the same working in a logistics operations in Afghanistan or is it a completely different kettle of ish? His experiences follow in his own words.

6pm Afghanistan time

It’s 6pm local time and I take my place at the back of the room as we prepare for the brieing. The winter sun has dropped out of the sky and the temperature is starting to fall. In the background, there is the constant noise of helicopters landing and taking off, and trucks moving around Camp Bastion. This is going to be a 60-plus vehicle combat logistics patrol (CLP), that’s a convoy to you and me, and we are going to a patrol base on the edge of the green zone. In the past, the patrol base we were delivering to didn’t have a road delivery, as it had been considered too dangerous.

I had already spent some time with 13 Air Assault Support Regiment, Royal Logistic Corps, the loggies that support 16 Air Assault Brigade (the Airborne Brigade).

I was previously told that on a CLP a few days earlier they were in a ierce gun battle with the Taliban. A tanker full of fuel had slipped off a narrow track and the trailer was hanging over a ditch. The only way to rescue it was to bring in the recovery vehicle and tow it out. The Taliban had seen this and tried to take advantage of the situation by launching an attack with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades. The loggies fought for several hours, recovering all equipment and personnel. While one soldier was shot in the leg, everyone else returned safely back to Camp Bastion after repelling the Taliban attack. So now I am all too aware of the dangers these people face every day – and the danger I’m getting myself into as well!

The brieing continued and Lt Rob Treanor explained that the brigade’s battle group had pushed the enemy back, therefore allowing a CLP to happen. That’s not to say it’s not dangerous – it’s all about risk management.

Back at the brieing, the CLP operation was planned in meticulous detail. The routes we would take, the support we could expect from Apache gunships, Jackal and Mastiff ighting vehicles and so on was all set out in advance. As were the various methods for countering improvised explosive devices (IED), communications, rations, water, personal and vehicle-mounted weapons and ammunition. Then, of course, there is the small matter of the purpose of the CLP – to provide the patrol base with all it would need to be maintained. That includes pretty much everything from food and drink to bombs and bullets, as well as fuel, spares, batteries and the equipment of war such as razor wire, Hesco (the material patrol bases are made out of) and sand bags.

They may be soldiers irst, but they are pretty decent logisticians too. They had spent the previous few days assembling their loads and driving round Camp Bastion, – which is bigger than the town of Reading – collecting kit and equipment and illing tankers..

The men and women of 13 Regiment were then tested on their knowledge with quick-ire questions on ‘actions on’ – or what we might call ‘what if’ situations. Every question was met with a correct answer, and the troops were sent away for an ‘enforced rest’ . It had already been a long day and we had to leave at 0400h.

Morning

I was introduced to the team that was going to look after me for the next 27 hours. Lt Dan Williams was not only the vehicle commander but also the troop commander – a huge responsibility for a young man who had only left Sandhurst 10 months earlier. Just getting the vehicles in the right order was a logistics challenge.

There was nowhere to park 60-plus vehicles, so they had to all join the snake at different parts of the road around camp. One by one they joined us as we left the safety of Camp Bastion and headed into the wilds of Helmand province.

I got to sit up front of a 24-tonne Ridgback vehicle with Sean North, 22, or Northy, as he is known. These heavily armoured vehicles are pretty snug inside, and when you remember the driver has to wear 20kg of body armour and helmet too, you start to recognise this is no ordinary trucking job.

Northy, a keen Blackburn supporter from Preston, could talk the hind legs off a donkey, which for me was pretty useful as I learned lots. Some of those things are, er, not repeatable in print and some things the Army won’t allow me to repeat as the safety of the soldiers is paramount – but what I am allowed to say is that their kit is amazing.

We took more than 60 vehicles through the economic capital of Helmand, a town called Geresk. This busy bustling town appeared to have no rules of the road: vehicles, mopeds and donkeys come at you from all directions. We had been warned about vehicle-borne suicide bombers, and any one of these could have been one. The drivers stayed calm and focused on steering these huge vehicles in and out of the trafic, being courteous and yet suficiently imposing to deter any potential insurgents.

Midday

I was acutely aware of the cupola on the top of our vehicle swinging back and forth with its general purpose machine gun covering us. As we left the madness of Geresk, once a Taliban stronghold, Northy explained how they only use the black top roads (constructed by the Royal Engineers) as the insurgents cannot hide IEDs as easily in them.

Almost on cue, we pulled off the highway and into the desert. The black top ran out and was replaced by a metalled road. Intelligence reports suggested that IEDs may have been planted around that area. Axle-deep in sand, we travelled at speed through this barren and desolate landscape, skirting villages and avoiding tracks. With the CLP kicking up clouds of dust and reducing visibility to a few metres, the skill of these young drivers was severely tested. After two hours, we rejoined the highway, where there was a river to cross. Before we got to the bridge a call came in that one of the vehicles had broken down, and ‘actions on’ kicked in. Once we had been told the area was clear of IEDs, I jumped out with Sgt Chris Sutherland, a good-humoured but no-nonsense senior non-commissioned oficer who took control. In a few minutes, the recovery vehicle was in place, the broken-down truck hooked up and we were on our way.

I was now in the back of the Ridgback listening in to LCpl Daryl Chassang on the radio arranging for the vehicle to be dropped off at another patrol base for repair.

There was a certain tension in the air as we approached the patrol base. We stopped short and ‘laagered up’ – the modern-day equivalent of putting your wagons in a circle. Not all the trucks could enter the patrol base at the same time and so had to form a defensive position a little short of the destination.

Once inside the patrol base, there was a lurry of activity, the forklift was unloaded and they started to unload the lat racks, while in another corner the sea containers were put down and the tankers were being prepared to pump the fuel into the empty tanks. Others prepared the next load of trucks, unstrapping loads and putting pallets down. The command vehicles turned into cookhouses as rations were prepared for those working. Job done, there were handshakes all round from the grateful International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) soldiers, who had been low on supplies. There was a bonus when some Gatorade was produced by our hosts – drinks all round and then the return to base.

Afternoon

I was driven back by Snowy and Jinx, as they are known, in their MAN Enhanced Platform Loading System. Our return journey followed a similar pattern; we picked up the broken truck – by now with its damaged prop shaft ixed – headed into Camp Bastion tired and dusty but, most importantly, with a sense of a job well done. As for me, well I too was pleased to be back in one piece and hoped I hadn’t been too much of pain to the men and women of 13 Regiment.

I was more than a little chuffed that I had been out to the green zone, the most dangerous place on the planet, and come back unscathed. Then came my Del Boy moment: I opened the door, missed the step and fell seven feet into the dust with the body armour taking my breath away. I was up on my feet with that look that said: “It’s OK, I knew that was going to happen.” I walked through the gates to a round of applause and lots of mickey-taking.

But I couldn’t have cared less: I was proud to have spent time in the company of these airborne loggies. ■