T HE bulk handling of dry and liquid commodities presents special

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 75

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

problems, no matter where the locale may be. The two major factors are that in most cases, dead mileage equals paid mileage, and that specialized

equipment of above-average cost has to be used. The rate for any commodity carried in bulk is considerably lower than that applied to the same item in packaged form, which particularly applies to refined products of the petroleum industry. The specialized equipment does not lend itself to easy adaptation to haul other types of bulk freight, and thus the carrier starts off at a considerable disadvantage.

As an example of revenue obtained for hauling refined products, take the haul across the Cascade Mountains, eastwards from Seattle, Washington. The particular run is 143 miles ,each way, and the rate for canned goads, in lots of a minimum of 40,000 lb., one of the lowest, is 38 cents per 100 lb. The load can be hauled on a flat-bed trailer or combination and, when unloaded, the carrier has a very good chance of picking up a return load, at the same or even a higher rate. The tanker operator hauls, legally, slightly more weight, but his rate is only 24 cents per 100 lb., and his equipment must return empty. One of the major tanker fleets in the Pacific Northwest, that of Inland Petroleum Transportation Co., Inc., Seattle, has built up a flourishing business over the past 26 'years. The company, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Pacific Gamble Robinson Company, also of Seattle, started life in 1935. It was started primarily as a means of speeding up delivery of fruit and apples, in particular from the famous Yakima Valley, Wenatchee and Okanogan Valley fruit growing districts to the markets and port of Seattle. Having to run its equipment eastwards empty, the company had a special trailer built, with a tank mounted under the flat bed, in which it was possible to haul 3,000 U.S. gallons of petrol to the areas mentioned, and it was planned to haul crated fruit westwards.

However, it soon became evident that this would not be practical, since in many cases fruit was not always available in the area expected, and sometimes was not even picked when the truck was ready to load. Even when a load was readily available, if it was for export the fire department would not permit a vehicle of this type within the port area, on the grounds that it presented a fire hazard, which necessitated transferring the load to a conventional vehicle. Under these circumstances, operating costs made the plan uneconomical, and it had to be abandoned.

At this point, Inland Petroleum Transportation Co., Inc., was formed with the object of building up a business handling refined products entirely. Since that time there has been steady progress and diversification of products hauled.

Originally, rates were compatible with the investment required, and a reasonable return achieved. As the times changed, and changes come very quickly in the U.S.A., competition from the railways increased, and rates were progressively reduced. Due to the geographical location of the bulk plants in relation to delivery points, the operation had to be based on a one-way haul basis.

Up to the mid-1950's, refined products were delivered from Puget Sound bulk plants, up and down the coast, hi.n major and more profitable hauls were over the Cascades into Eastern Washington, and into British Columbia, where certain items were not produced or stored in large quantities. The State of Washington is chiefly agricultural by nature, and one of the world's largest producers of timber and grain. At one time, it was intended to adapt some vehicles to haul grain back to the coast elevators, but it was found that time lost and the expense involved in steam cleaning made it impractical.

The vast Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, that followed the building of the Grand Coulee and other, dams on the Columbia River, which reached its peak in the early 1950's, changed the economy of Eastern Washington, and dry land farming became only a part of the agricultural picture. New communities grew up quite rapidly, especially around new U.S. Government installations. The Trans-Mountain Pipeline, from the oilfields around Edmonton, Alberta, was being laid towards the Pacific coast. With an eye to reduced transp&tation costs, the major oil companies started building large bulk installations at Pasco, the navigable headwaters of the Columbia River, which then was the northernmost terminal of the Standard Oil Company's pipeline from Salt Lake City, carrying petroleum products. Other refined products are barged up the Columbia River, about 250 air miles, bypassing four of the river's completed dams.

While these changes were in progress, the first refinery was built on Puget Sound, near Ferndale, a few miles south of the Canadian border, by the Mobil Oil Company. Quickly following this, both the Shell Oil Co. and the Texas Company built refineries, adjacent to each other, all of which have deep water facilities, and are able to berth the world's largest tankers. This latter site is near Anacortes, about 25 miles farther sOuth. Allthree are now connected with the Canadian crude pipeline. The Puget Sound area bulk plants are largely supplied from these refineries, as far South as Portland, Oregon, by tanker and barge.

As a point of interest, crude is pumped from the Alberta originating point, over 900 miles away, on a strict schedule, to the three refineries, and crude for one refinery is separated from that for one of the others by a coloured chemical which does not mix with the crude. It is stated that it takes 30 days for any one consignment to reach the Puget Sound, and of course, once pumping has started, the hatch cannot be cancelled, which at times of short storage space, presents problems. Pumping is continuous six days a week, with the seventh day being reserved for maintenance.

Trucks for Speed

Where steady shipments are made, railway tank cars are heavily used, but in cases where speed is necessary or storage limited, trucks are usually employed. Also where a product is loaded hot, because the railway tanks cars are not insulated, and time would be wasted in reheating before it was possible to pump off a load. Products are loaded at temperatures varying from 120°E. to 480*E. On the shorter hauls, the railways are not able to compete in speed of service, and in many cases, where the smaller tank car is spotted for loading, the tanker can haul almost an equal gallonage. This in the case of the 8,000-gal, railway tank car, which is slightly less in capacity than the average road tanker load of petrol.

Changes of this nature forced the road tanker operators to base vehicles in the vicinity of the Eastern Washington bulk storage plants at Pasco, since their business had been seriously affected.

These changes forced. I.P.T. to look for other products to haul, since the heavy curtailment of the more profitable D16 long hauls came quickly after the refineries started producing. The first venture was the purchase of an L.P.G. tanker, to serve points now desirous of using this cheaper product, but situated beyond service available from the railways or city gas lines. In the past few years, this has grown into a major haul, which includes, by interchange rights, hauling empty tankers to and from the refineries, for shipment by barge to Alaska. Unfortunately, these tankers are heavy, and the payload is only in the vicinity of 16-17 short tons. The legal maximum gross load is 76,000 lb. for a truck and a

trailer, and 73,280-1b. for a semi-trailer combination.

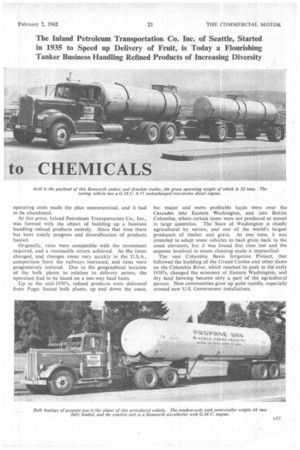

Still further sources of income had to be found and the company turned to liquid fertilizers and to chemicals, both those which can be hauled in normal tanks and those requiring pressurization. Some tankers made of 316 extralow-carbon stainless steel must be used for certain chemicals, while others can be hauled in aluminium tanks. A long list of chemicals is now hauled, which includes sodium chlorate, anhydrous ammonia, acids, and many of the chemicals used in the pulp industry_ In the course of only a few years, I.P.T. has built up chemical haulage to become a major part of its business, while still retaining its previous refined products business.

Five-year Increase

In five years, the amounts of chemicals hauled to the lumber industry, and paper-products manufacturers, have increased very considerably, as also has the liquid fertilizer movement, which is considerably heavy in spring and autumn. Since the manufacturing plants of the leading chemical corporations are rather widely spaced, some of these hauls are as long as 800 miles, although the average is probably closer to 200 miles. Where compressed gases are hauled, to date, only steel tanks are in use, but experiments are in progress in the California plant of a leading aluminium manufacturer, and it is expected that an aluminium tanker will be made soon.

The chemical field is becoming larger day by day, and at this time embraces mining, boat building, glass-fibre products, cement manufacture, paints, glues, adhesives, soap and detergent manufacture. All of these industries are discovering that it is far more economical and con venient to accept chemicals in hulk rather than in packaged form. In most cases, where shipment is by rail, the consignee must supply manpower to unload the tankers, but where trucks are used equipped with their own pumping means, the drivers do the work, a feature included in the transportation cost. On this basis, delivery can be made on a 24-hour coverage. To date, the movement of chemicals has not reached the point where the special equipment can be kept in use constantly, and therefore the heavy investment raises the operating costs considerably on a mileage basis. It is hoped that in time this part of the fleet will be utilized to near its maximum potential.

_Taxation is one of the major costs to the American operator, particularly where their operation embraces several States. Vehicles must be registered in each State, and this and various other fees are levied, one of which is the ton-mile tax, which coversall loaded miles run in that State. Unfortunately each State levies this.tax at a different rate, which complicates book-keeping. 1.P.T., operating constantly in four States and one Canadian province, must carefully select which vehicles to licence in one, several, or all taxation areas concerned. The cost of these licences, per vehicle, amounts to approximately $3,500 p.a., covering all five taxation areas.

Operating -costs are naturally kept to a minimum, but not by the process of skimping on maintenance. Excellent co-operation between shop personnel and drivers is maintained, the latter being encouraged to try to explain symptoms of developing troubles to mechanics, rather than the somewhat normal procedure where mechanics appear to labour under the impression that a driver cannot possibly know what is wrong with a vehicle or engine. This is a policy which has paid dividends in saved manhours and lost time while a vehicle is tide up for trouble to be located.

Big-engine Economy The G.M.C. two-stroke diesel, chiefly in use, is operated on both premium and regular diesel fuel, on about a 50-50 basis, the 6-71 models returning a fuel mileage of between 41, and 5,1 m.p.g. (U.S.). The new 8V-71 engines do somewhat better proving that the smallest swept volume engine capable of handling a specific load is not always the most economical in operation. This engine has proved itself highly satisfactory, and several have been run as much as 400,000 miles before complete overhaul. The fleet annual mileage is very close to 4 million miles, for which a gross revenue of $2m. is obtained. Road failures are few, and chiefly caused by stuck injectors, dirt and water in fuel filters, fuel line and battery failures. The 6-71 engine is equipped with only a 12v. starting system.

Tyres, of which both the tube and tubeless types are in use, cost approximately 2 cents per mile. Climatic conditions under which I.P.T. operates have a considerable bearing on certain costs. These conditions vary from sea level to 6,500 ft. altitude, extremes in humidity, and temperatures from sub-zero to over 100°F. in midsummer. Both sub-zero and high-altitude operation has a particularly noticeable effect on fuel consumption of a two-stroke diesel engine.

Cargo discharge pumps have been and, to a certain extent, still are a problem. To handle all types of refined products and the numerous chemicals handled, stainless steel and mild steel are required. Some pumps are built completely of aluminium. Weight and cost are a factor, since one particular pump cost $1,000. Several types are in use—centrifugal, gear and a new type which is an adaptation of a supercharger. For L.P.G. tankers, 1.P.T. has found that compressors are more practical and pump the tank completely clean. Cargo hoses are an item of considerable expense, and couplings are high in replacement cost. A new type has recently been introduced, cheaper in replacement cost and very reliable, with gaskets which seem to have an almost indefinite life.

The various hoses required to handle chemicals, in both 21-in. and 3-in, diameter, which are normal for refined products, have been abandoned due to the high cost. These sizes cost between $2.50 and $3.60 per foot, neoprene lined. A general-purpose cargo hose for chemicals, capable of handling sulphuric acid, is the Hyperlon-lined pressure type, and in 2-in, diameter, costs between $6.50 and $9.00 per foot according to quality. Each petroleum tanker unit carries two hoses, one 12-16 ft. long and the other 18-22 ft. long—a considerable investment, Acid tankers must use stainless-steel piping, where pressure is used.

Equipment costs are high—an aluminium truck and trailer tanker combination complete costs approximately $35,000, while a similar unit with stainless-steel tanks, costs between $45,000 and $47,000. Acid tankers and L.P.G. tanks are extremely high in initial cost.

Operating costs on the fleet average 45 cents per mile, with a low of 30 cents and a high on local delivery of $1.50. Of this sum, 14+ cents is absorbed in driver's wages and fringe benefits, such as a health and welfare scheme, and retirement plan, included in the union cOntract. The company has its own profit-sharing plan, in which all employees after five years' service may partake.

Numerous vehicles are assigned to hauling turbine fuel for several airlines, and are reserved exclusively for this purpose. Special tankers for anhydrous ammonia are hauled on a " hire " basis for a leading chemical corporation, I.P.T. supplying the tractor and driver only.

The latest venture is into the bulk cement business, and the company has been successful in obtaining a haul, for which it has ordered two air-discharge pieces of equip ment. One is articulated, and the other is a so-called " train " consisting of a short-wheelbase tractor and semitrailer pulling a full trailer. In both cases, the Kenworth Company„ also of Seattle, is building the tractor units, which will be powered by 8V-71 G.M.C. diesels.

For many years, I.P.T. has been operating from a threelane service facility, with two bays reserved for overhaul. Doing over 90% of the maintenance in these shops, for a fleet, of 110 units, these premises have become totally inadequate. At the present time, on a long-term lease, a new office building and service installation is being built. The service facilities include seven service lanes and a much larger shop, and with these larger premises the company feels that its requirements will be satisfactorily served for the next 20 years.