Bus Drivip an Arm( 3ecomes ir Job

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By L. J. COT

M.I.R.T

How often does a bus driver change gear? This question was once put to me and after an

exhaustive survey over a recognized route in London with counter meters fitted to the controls, it was discovered that upwards of 3.000 gear changes were made per day. Brake applications amounted to approximately 1.000. Pedal and steering effort was also measured, and the results proved that operating the clutch and gear lever was by far the most arduous part of bus driving.

I borrowed a Dennis Dominant for a morning and drove over the same route in armchair comfort. There is no clutch pedal to the Dominant, and the gear lever is only 3-4 ins long and can be flicked into position,

with one finger. .

Undoubtedly, the Hobbs transmission used in the vehicle is a great advance in clutch and gearbox design. It takes all the hard work out of driving, appears to have no effect on fuel consumption and improves passenger comfort. My short trial in town was made without toad or passengers, and any harshness or Odder in the take-up of the transmission between gear changes would immediately have been apparent.

Full-throttle Gear Changes It is possible to cause a jerk when engaging bottom gear, but it needs a careless driver to do so. Apart from r this, full-throttle gear changes can be made without any . discomfort to the passengers.

My first trials were made on an overseas model. equipped with a suPercharged engine, but for comparative purposes I conducted acceleration and consumption tests on a home model with a normally aspirated power unit and a fixed-ratio axle.

The 'Dennis standard vertical 7.585-litre engine has been modified for its horizontal underfloor position, and the supercharged version has special pistons to reduce the compression ratio from 15 to 1 to 14 to 1. Driven at 11: times engine speed, the Marshall blower gives a moderate boost of 21 to 81. lb. per sq. in. through the governed range of the engine, and is linked to a control on the fuel pump to limit the rack movement below 1,200 r.p.m. This prevents a dirty exhaust and a waste of fuel when on full torque at low engine speed.

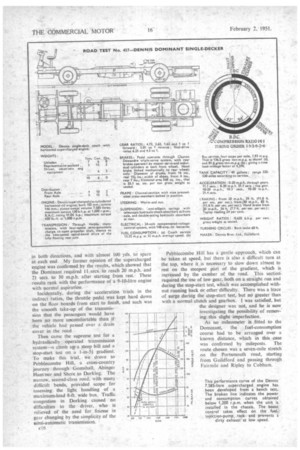

In place of the conventional clutch and gearbox, the Dominant employs a transmission incorporating a fourspeed planetary gearbox with hydraulically Controlled wet-plate clutches and torque-reaction brakes. The Hobbs transmission unit was described in "The Commercial Motor" on August 25, 1950. This arrangement c8 has no external clutch Control, thereby dispensing with the pedal, and changes of ratio are made by a single lever.

The model tested with a load was equipped with an Eaton two-speed rear axle, having ratios of 6.24 to 1 and .1.5 to 1, a Clayton Dewandre triple-servo vacuum braking system, and 10.00 by 20-in. tyres. A two-speed axle and vacuum braking system are optional items in the export model, but as the main purpose of my test was to assess the value of the Hobbs transmission and the general behaviour of the vehicle, these features are not of immediate concern.

Loaded to the Limit Fitted with a Strachans 42-seater coach body, the test model weighed 7 tons 6 cwt., unladen, but with the load carried the gross weight amounted to 10 tons 6 cwt. This represented a full complement of passengers, plus a generous allowance for luggage in the boot at the rear.

At the start of the day, the coach was driven over the approach of the Hogs Back to Milford and the accuracy of the speedometer was checked on the way before starting the short performance trials. I listened carefully for blower whine, but it was barely audible above the air-flow noise of the fan, and would certainly not be heard by the average passenger.

The Dominant haS. punch in its acceleration, especially at engine speeds above 20 m.p.h., and the works tester was not reluctant to show how rapidly and safely slowermoving traffic could be overtaken. Thespeedometer was a little pessimistic and slight corrections were made throughout the trials to arrive at the correct results.

First came the measured braking distance, using a pressure switch on the pedal to operate an air pistol attached to the exterior of the body. This produced an average stopping distance, measured from the first pressure on the pedal to the point of coming to rest, of 82 ft. from 30 m.p.h. and 39 ft. from 20 m.p.h. A modified Dobbie .MacInnes accelerometer was employed to determine the retardation curve, which showed an 0.6-sec. delay in building up to full pressure.

The road chosen for these trials appeared to be too short for all acceleration tests. I was, therefore, surprised when the Dominant was accelerated to 30 m.p.h. c9 in both directions, and with almost 100 yds. to spare at each end. My former opinion of the supercharged engine was confirmed by the results, which showed that the Dominant required 11 secs. to reach 20 m.p.h. and 21 secs. to 30 m.p.h. after starting from rest. These results rank with the performance of a 9-10-litre engine with normal aspiration.

Incidentally, during the acceleration trials in the indirect ratios, the throttle pedal was kept hard down on the Floor boards from start to finish, and such was the smooth take-up of the transmission that the passengers would have been no more uncomfortable than if the vehicle had passed over a drain co\ er in the road Then came the supreme test for a hydraulically operated transmission systern—a chmb up a steep hill and a stop-start test on a 1-in-5i gradient. To make this trial, we drove to Pebbleeombe Hill, a cross-country journey through Gomshall, Abinger Haiwncr and Shere to Dorking. The narrow, second-class road, with many difficult bends, provided scope for assessing the light handling of a maximum-load 8-ft. wide bus. Traffic congestion in Dorking caused no difficulties to the driver, who is relieved of the need for finesse in gear changing by the simplicity of the semi-automatic transmission.

c10

Pebblecombe Hill has a gentle approach, which can be taken at speed, but there is also a difficult turn at the top, where it is necessary to slow down almost to rest on the steepest part of the gradient, which is increased by the camber of the road. This section, required the use of low gear, both on a straight run and during the stop-start test, which was accomplished without running back or other difficulty. There was a trace of surge during the stop-start test, but no greater than with a normal clutch and gearbox. 1 was satisfied, but the designer was not, and he is now investigating the possibility of removing this slight imperfection.

As no mileometer is fitted to the Dominant, the fuel-consumption course had to be arranged over a known distance, which in this case was confirmed by mileposts. The route chosen was a seven-mile stretch on the Portsmouth road, starting from Guildford and passing through Fairmile and Ripley to Cobham. There are slight undulations between Guildford and Cobham, but a large-engined single-decker ought to be able to negotiate them in direct drive. The supercharged Dennis succeeded in doing so, and. apart from two traffic stops the indirect ratios were not needed during the sevenmile outward run. I was disturbed by the heat loss through the engine-cooling system, which incorporated a tropical radiator, but unfoitunately did not include a thermostat on the vehicle tested.

Although almost five-sixths of the frontal area of the radiator was covered, there was still ample cooling from the light-alloy case Surrounding the tube stack. With an external temperature of 45 degrees F.. the coolant could not he encouraged beyond 127 degrees F. I would have preferred an increase of 60 degrees F. in the temperature of the engine in the interests of fuel economy.

During a straight test outlkards and returning to the Aarting point, the Dominant averaged 13.25 m.p.g. at in average speed of 32 m.p.h. A second trial made over he same course, with four stops to every mile, proWeed a fuel return of 7.93 m.p.g. Compared with the ..ancet chassis, the supercharged Dominant uses tpproximately 10 per cent. more fuel. As a check. the maker supplied me with a domestic Dominant with an unblown power unit, which was tested over the same course.

Running conditions of weight, etc„ were made the same as for the previous trial, but there was a slight variation in overall ratios, because of the smaller tyres and a fixed-ratio axle. This second Dominant had the Hobbs transmission and a Strachans 42-seater coach body of similar frontal area to the supercharged vehicle.

The unblown version gave fuel-consumption rates of 14.75 m.p.g.. on the continuous-running test, at an average speed of 30.4 m.p.h., and 8.15 m.p.g. on localservice trials. These results indicate that the slight increase in consumption can be attributed to supercharging, and that no additional loss is incurred in this special transmission system.

The Lancet and Dominant normally aspirated chassis have practically identical consumption rates, which confirms the operational 'experience of the Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Co., Ltd., which is also running a single-deck bus equipped with the Hobbs transmission for comparison with standard vehicles.

During the acceleration trials, the second vehicle could not read! 30 m.p.h. in all tests on the Milford road. This was an early indication of where the blown version scored. We then drove to Peasmarsh, where acceleration from rest to 30 m.p.h. occupied 23.8 secs. It took 34.4 secs. to reach 30 m.p.h. from a rolling start. A detailed comparative analysis has been compiled in an accompanying table. There was a marked difference in performance of the two Dominants, and after a journey on the supercharged version 1 was convinced that the slight increase in fuel consumption is cheap in relation to the improvement in performance, saving on journey time and ability to overtake with ease.

After these extended trials I decided that the Dennis underfloor-engined chassis was one of the smoothest and quietest of its class, and one which will be greatly favoured by passengers. The advantages afforded to the driver in respect of gear changing have already been described, but further attractions are the freedom from projections in the cab and the sturdy case surrounding the steering, which appears to add to its rigidity. Although over 40 per cent. of the gross load was carried on the front axle during the trials, the steering was as light and accurate as on any passenger chassis I have yet tested

In addition to the two Dominant models tested, there are short, medium and long-wheelbase 8-ft.-wide singledeckei s for the overseas market, and a 16-ft. 9-in.wheelbase chassis of 7-ft. 6-in, width for home use. The overseas models, with right or left-hand drive, are available with 11.00 by 20-in. tyres. The medium and long-wheelbase versions are suitable for body lengths of 33 ft. and 35 ft.

A single-speed double-reduction axle is advocated for overseas service, because it increases the ground clear ance from 11 ins. to 12 ins. The single-speed axle recommended has a bevel drive to the differential, and a double-reduction drive at the wheel hubs. The supercharged engine is available primarily for these overseas models, and the unblown engine is recommended foi use in home models, in conjunction with the two-speed axle.