B ECA USE of topographical conditions, longdistance fuel distribution in Northern

Page 57

Page 58

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

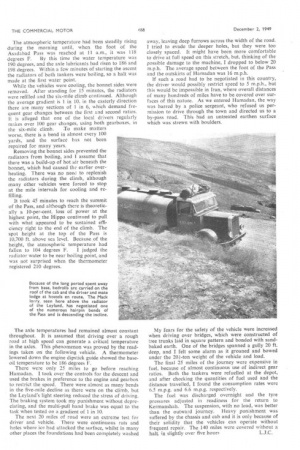

Iran is by road, instead of by pipe line, which is normal procedure in all other parts of the country. Leyland tankers have been employed for this task for many years, a slightly modified TC9 model having been found best fitted for the work.

The TC9 is, however, being replaced on this work by the latest Leyland Super Hippo, a model specially designed for overseas conditions. The Leyland 9.8-litre 125 b.h.p. direct-injection engine gives a good powerto-weight ratio, and with the main and auxiliary gearboxes which are fitted, a high torque is available at the wheels in the lower ratios.

The main features of the Leyland engine include the construction of the crankcase and cylinder block from a single iron casting, pre-finished cylinder liners, sevenbearing nitrided crankshaft, Stellite-faced valves and seats, and efficient filtration in the fuel, air and lubrication systems.

The 161-in.-diameter single-dry-plate clutch is smooth in action, well ventilated and easy to adjust. A simple positive adjustment permits the full thickness of the facing to be used before renewal is required. Positive lubrication is incorporated in the sturdy five-speed direct-drive gearbox. Fifth, fourth and third speeds are in constant mesh, and the fourth and third ratios have helical gears for quiet operation.

Heavy-duty Axles Robustly built to withstand rough operation, the centre and rear axles have overhead worm drives with 9-in. centres. The axles are connected by a single inverted semi-elliptic spring at each side, the spring saddles being mounted on trunnion bearings. The outer ends of the springs are attached to the axles by swivelling trunnions.

A compressed-air braking system is employed, with the brake pedal directly coupled to the air-pressure control valve and an air cylinder to each wheel. The shoes are cam-operated, the total friction area being 916 sq. ins. The Super Hippo is a bonneted model, the vehicle on which I made my journey having left-hand control. This machine has a tropical radiator with a frontal area of 6 sq. ft., and the cooling system has a total capacity of eight gallons. A thermostatic control is provided for rapid warming up from cold.

I made a 300-mile journey by air from Abadan to Kermanshah to drive one of these Hippos on its home ground. Because I was pressed for time, I arranged to make one of the shortest journeys, which was to Hamadan, a distance of 140 miles from Kermanshah. A second vehicle of the same type, operating with an experimental axle lubricant, was included in the test to yield comparative results.

It was 7 a.m. when the two tankers left Kermanshah. Mr. G. Adcock (formerly engineer to the Devon General Omnibus and Touring Co., Ltd., and Leicester Transport Department) acted as my co-driver on the first machine, and a Syrian driver was in charge of the second vehicle. The road between Kermanshah and Hamadan was pant of the Aid-to-Russia route and was reconstructed during the war, but little attempt has been made to maintain its surface since 1945, and, consequently, the foundations in many places have been washed away.

The first 60 miles were covered at good speed, the road being straight and the surface in a reasonable condition. A 20-minute halt was made at Bisitum, 25 miles after leaving the depot, to take the atmospheric and operating temperatures. The average speed to this point was 30 m.p.h. As the day was yet young, the atmospheric temperature was a mere 83 degrees F,, and the radiator top-tank temperature registered 173 degrees and axle temperature 159 and 154 degrees F.

Road Foundations Disappear

I drove for the next 35 miles and the road surface, although good for the major part, had a number of bad patches where the foundations had been attacked by the mountain streams. The speed had to be restricted over the rough patches, but, even so, the average during my spell of driving was 25 m.p.h. Although the road had a series of slight gradients, the engine was turning over at maximum revolutions for the greater part of the run, and there was an abundance of power to spare.

This indicated that a slightly higher final-drive ratio or a step-up ratio auxiliary gearbox might be beneficial to fuel consumption and average speed. The first serious gradient was encountered soon after leaving Kancavar, where the Tapley meter registered between 1 in 10 to 1 in 71 for almost a mile. I soon found that the best technique was to engage second gear of the main gearbox and use the ratios of the auxiliary gearbox according to the severity of the gradient. After passing over the brow of the hill, the road surface became steadily worse, and I had difficulty in steering around the deeper holes.

The atmospheric temperature had been steadily rising during the morning until, when the foot of the Asadabad Pass was reached at 11 a.m., it was 118 degrees F. By this time the water temperature was 190 degrees, and the axle lubricants had risen to 186 and 198 degrees. Within a few minutes of starting the ascent the radiators of both tankers were boiling, so a halt was made at the first water point.

While the vehicles were cooling, the bonnet sides were removed. After standing for 15 minutes, the radiators were refilled and the six-mile climb continued. Although the average gradient is 1 in 10, in the easterly direction there are many sections of 1 in 6, which demand frequent gear changes between the first and second ratios. It is alleged that one of the local drivers regularly makes over 100 gear changes, using both gearboxes, in the six-mile climb. To make matters worse, there is a bend in almost every 100 yards, and the surface has not been repaired for many years.

Removing the bonnet sides prevented the radiators from boiling, and I assume that there was a build-up of hot air beneath the bonnet, which had caused the earlier overheating. There was no need to replenish the radiators during the climb, although many Other vehicles were forced to stop at the mile intervals for cooling and refilling.

It took 45 minutes to reach the summit of the Pass, and although there is theoretically a 10-per-cent. loss of power at the highest point, the Hippo continued to pull with what appeared to be sustained efficiency right to the end of the climb. The spot height at the top of the Pass is 10,700 ft. above sea level. Because of the height, the atmospheric temperature had

fallen to 104 degrees F. I judged the radiator water to be near boiling point, and was not surprised when the thermometer registered 210 degrees.

The axle temperatures had remained almost constant throughout. It is assumed that driving over a rough road at high speed can generate a critical temperature in the axles. This phenomenon was proved by the readings taken on the following vehicle. A thermometer lowered down the engine dipstick guide showed the baseoil temperature to be 186 degrees F.

There were only 25 miles to go before reaching Hamadan. I took over the controls for the descent and used the brakes in preference to the engine and gearbox to restrict the speed. There were almost as many bends in the five-mile decline as there were on the climb, but the Leyland's light steering reduced the stress of driving. The braking system took my punishment without depreciating, and the multi-pull hand brake was equal to the task when tested on a gradient of 1 in 10.

The next 20 miles of road were an extreme test for driver and vehicle. There were continuous ruts and holes where ice had attacked the surface, whilst in many other places the foundations had been completely washed away, leaving deep furrows across the width of the road. I tried to evade the deeper holes, but they were too closely spaced. It might have been more comfortable to drive at full speed on this stretch, but, thinking of the possible damage to the machine, I dropped to below 20 m.p.h. The average speed between the foot of the Pass and the outskirts of Hamadan was 16 m.p.h.

If such a road had to be negotiated in this country, the driver would possibly restrict speed to 5 m.p.h., but this would be impossible in Iran, where overall distances of many hundreds of miles have to be covered over surfaces of this nature. As we entered Hamadan, the way was barred by a police sergeant, who refused us permission to drive through the town and directed us to a by-pass road. This had an untreated earthen surface which was strewn with boulders.

My fears for the safety of the vehicle were increased when driving over bridges, which were constructed of tree trunks laid in square pattern and bonded with sandbaked earth. One of the bridges spanned a gully 20 ft. deep, and I felt some alarm as it groaned and bowed under the 201-ton weight of the vehicle and load.

The final 25 miles of the journey were expensive in fuel, because of almost continuous use of indirect gear ratios. Both the tankers were refuelled at the depot, and after checking the quantities of fuel used and the distance travelled, I found the consumption rates were 6.5 m.p.g. and 6.6 m.p.g. respectively.

The fuel was discharged overnight and the tyre pressures adjusted in readiness for the return to Kermanshah. The suspension, with no load, was better than the outward journey, Heavy punishment was suffered by the chassis and cab and it is only because of their solidity that the vehicles can operate without frequent repair. The 140 miles were covered without a halt in slightly over five hours L.J.C.