COMPLD ROBLEM of ar xpanding Company

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

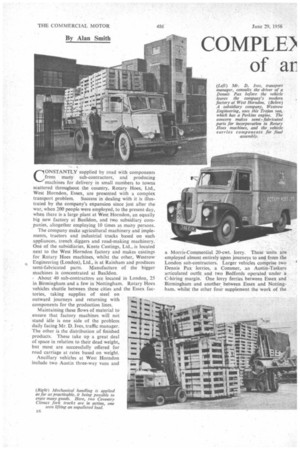

CONSTANTLY supplied by road with components from many sub-contractors, and producing machines for delivery in small numbers to towns scattered throughout the country, Rotary Hoes, Ltd., West Horndon, Essex, are presented with a complex transport problem. Success in dealing with it is illustrated by the company's expansion since just after the war, when 200 people were employed, to the present day, when there is a large plant at West Horndon, an equally big new factory at Basildon, and two subsidiary companies, altogether employing 10 times as many persons.

The company make agricultural machinery and implements, tractors and industrial trucks based on such appliances, trench diggers and road-making machinery. One of the subsidiaries, Knete Castings, Ltd.,_is located next to the West Horndon factory and makes castings for Rotary Hoes machines, whilst the other, Westrow Engineering (London), Ltd., is at Rainham and produces semi-fabricated parts. Manufacture of the bigger machines is concentrated at Basildon.

,About 40 sub-contractors are located in London, 25

in Birmingham and a few in Nottingham. Rotary Hoes vehicles shuttle between these cities and the Essex factories, taking supplies of steel on outward journeys and returning with components for the production lines.

Maintaining these flows of material to ensure that factory machines will not stand idle is one side of the problem daily facing Mr. D. Ives, traffic manager.

The other is the distribution of finished products. These take up a great deal of space in relation to their dead weight, but most are successfully offered for road carriage at rates based on weight.

Ancillary vehicles at West Horndon include two Austin three-way vans and

a Morris-Commercial 20-cwt. lorry. These units are employed almost entirely upon journeys to and from the London sub-contractors. Larger vehicles comprise two Dennis Pax lorries, a Commer, an Austin-Taskers articulated outfit and two Bedfords operated under a C-hiring margin. One lorry ferries between Essex and Birmingham and another. between Essex and Nottingham. whilst the other four supplement the work of the

and a Thames 10-cwt. van are used for field-service work , and installations. Two Thames lorries are engaged within the factory confines on the movement of fuel and materials, and four small vans are held as a reserve for short-notice use by production chasers, or for emergency collections.

The Westrow concern have a Thames 5-6-tonner and a Trojan van, and Knete Castings a Thames 3-4-tonner and a Bradford van. The remaining Essex-based vehicles are a Ford and a Bradford works ambulance, one at each factory, and a Bedford 5-6-tonner used for sales demonstrations.

This vehicle (The Commercial Motor, October 7, 1955) was the first lorry to be flown on a scheduled commercial flight to the Continent. The company have modified the body for easy loading by arranging for therear to drop down at an incline.

The articulated vehicle is generally used with normal-level 8-ton semi-trailer with a 20-ft. platform, but the dompany have a low-loading semi-trailer for loading and unloading heavy machinery and tractors on site, or for demonstrations. The Birmingham vehicle is loaded with raw material for subcontractors on a Tuesday night and spends the rest of the week in the Midlands calling at suppliers, returning with parts for the following week's production. The Nottingham vehicle, with fewer calls to make, departs on a Thursday.

The three London vehibles each cover about 100 miles a day. Often it is necessary for a sub-contractor to be called upon several times daily to maintain a steady flow of supplies to the factory. One van leaves at 5-6 a.m., as may be necessary, if a load of parts is awaiting collection at a London rail terminus after delivery there from a subcontractor by overnight passenger train. A second van sets out about an hour later and the third after a similar interval.

Only a small proportion of the outgoing loads travels by ancillary transport. At one time it was intended tci open a series of depots throughout the country to which machinery could be carried in full vehicle-loads, for final distribution by small locally based lorries. This scheme has been realized to the extent that a depot was started at Spalding.

This depot continues to operate but has not been augmented. A Bedford 5-6-tonner collects machinery from West Horndon twice a week and deliveries are made by three Austin A40 pick-ups, except those of larger units, for which the Bedford is required. West Horndon is also, in effect, a depot, for Rotary Hoes themselves deliver by C-licence transport to their dealers in Kent, Sussex and Hants; also crates of spares and parts are taken to Folkestone for onward consignment to the company's manufacturing associate near Paris.

Transport to other parts of the country, however, is not according to plans once envisaged. One reason is that the extremely rapid growth of the company has necessitated concentration upon increasing factory plant and output, but the major difficulty lies in the widespread nature of demands by customers. Mr. Ives showed me a schedule of a typical day's deliveries. It comprised a list of loads to places great distances apart, each consignment being for only one or a few machines.

Because the pattern of outgoing loads was irregular, it was at present impracticable to superimpose upon it a so-called rationalized distribution system involving regular factory-depot journeys. A delivery_ahrough a depot to an isolated customer might haye to wait until a full load to that depot could be made up. Such a delay could not be considered, if only because of the build-up of machines awaiting dispatch at the factory. This could be substantial, as the word " isolated " applied to many customers.

A methodical distribution system, of the kind common to many manufacturers and other operators handling nation-wide traffic, might be possible in time, viten stocks could be built up in different areas. Factory-depot haulage would then be a matter of replenishing reserves rather than a stage in a transhipment movement that had quickly to be effected. So far, however, production has been strained to keep pace with demands.

At the time of my visit, the Austin Taskers was leaving the factory with a load of machines for stocking in one locality. Mr. Ives said that it was the first aggregated load that it had been possible to make up for a long time. Demand slackened in the winter, from a summer peak at the rate of 2,000 outgoing machines a week, and it was possible to build up area reserves.

The economical working of the Spalding depot was made possible because it served an agricultural area— Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire. Leicestershire and Norfolk—in which there was a steady demand compacted geographically within limits compatible with systematic ancillary transport operation.

Rail Rate Quoted

When deliveries to other parts of the country were made, a cost of carriage was quoted at the railway rate. It was, however, desirable to use road transport because this was much speedier. On the other hand, general road haulage charges were higher than rail. This was perhaps because a prohibitive element was contained in various hauliers' quotations, as the greater part of the company's traffic was to places remote from the country's major road arteries, and many carriers were disinclined to handle it.

There was thus a twofold problem. Finished products averaged 15-cwt. deadweight per 2 tons of lorry capacity; meaning, for example, that a fully laden 6-ton lorry

carried 45 cwt. of machinery. Obviously most hauliers would wish to charge on the basis of occupied capacity,, the reverse of railway quotations based on weight. The goods were, however, offered at rates according to the railway schedule. Mr. Ives quoted a charge of £4 15s. For 2 tons of machinery being sent to Northallerton.

When customers were advised of the forthcoming dispatch of a machine, they were notified of the cost of carriage and told that this was the rail rate, although road delivery would be made if it would save time.

"Why," I asked, "if you prefer road transport, do you not pay the appropriate road charge?"

Rail Rate as Basis

"Because that would be higher than the rail rate upon which we base our distribution expenses, and involve us in a loss," Mr. Ives explained.

Loads offered to hauliers at the railway rate went at the carrier's convenience, and this might entail holding back a machine at the factory until a lorry could collect it. Even it a few days' delay was involved, however, delivery was still quicker than by rail. If a customer wanted the machine urgently, he would in such a case be quoted the road haulage rate, on the understanding that delivery by road would be done without delay.

British Road Services gave the company good service from their Upminster depot, the manager of which Mr. Ives knew personalty_ When this closed down, it was at first difficult to find re-instated private hauliers to carry the traffic. Most independent hauliers, said Mr. Ives, seemed to be interested in loads only to the ch;ef provincial cities.

He was not inclined to consign his traffic through clearing houses, but he was successful in finding a haulage company specializing in the distribution of goods to any part of the country, not necessarily on the major routes. This concern was Huish Transport Services. Ltd., 40 Havannah Street, London, E.14.

Having toads to send to many and various districts. sometimes • under sub-contract, Huish were able to fit in Rotary Hoes' traffic with their broad operations. A machine might conveniently complete a lorry-load of mixed goods, and in such circumstances was acceptable at the rate quoted.

The association with this concern has worked well. Under a gentleman's agreement, Huish are given first option on the carriage of Rotary Hoes' steel requirements from Durham. Mr. Ives' internal telephone rang. The buying department wanted a load of steel brought down from West Hartlepool and delivered at the factory early next morning. An outside call to Huish and the movement was arranged.

Despite the difficulties described, some 75 per cent. of Rotary Hoes' products is delivered by road and 15 per cent. by rail. The remaining 10 per cent. is by sea to parts such as Scotland, Ireland and the Channel . Islands, land distribution from the farther ports being by shipping companies' services. A fractional percentage is represented by exports flown from Southend Airport by Air Charter, Ltd.

Ancillary transport is often employed to take export consignments to the docks. Delays to vehicles are not often experienced when big consignments are taken to London, and a lorry sent off in the morning can usually be assured of a return by the afternoon. Small lots. however, involve hold-ups. The position eased when the No. 7 receiving shed specifically • for smalls was introduced, but there are delays even there.

Export Loads ' Mr. Ives' daily routine entails an early afternoon visit to the dispatch foreman to ascertain the amount of transport capacity required for .export loads. Later he receives from the production department a list of subcontractors and suppliers who have to be called upon the following day, and meanwhile collects a list of orders for the next morning's outgoing loads of finished machinery. Some spares might have to be distributed by passenger train; post or road.

Having collated a picture of the incoming and outgoing traffic, he next makes out a working programme for the company's vehicles and hired transport. By the evening a full schedule and all drivers* work sheets are completed.

The plan usually entails last-minute alterations, By 8.30 a.m. the next day, extra clemands,may have arisen and the allocation of vehicles would need re-shufiing. During the day, too, there are likely to be unexpected calls for transport. Mr: Ives pointed out that he worked his department with only one assistant—Mr. R. Elliott, it former driver.

Aged 30, Mr. Ives is typical of many of thecompany's executives. He joined the company in 1946, after working in a London insurance office, to assist in the shipping department. All distribution gradually came within this department's sphere and that section dealing solely with exports was later moved to London. Mr. Ives remained and in time assumed his present position when the departmental head left the company.

Friendly Spirit His lack of seniority in years is no drawback in exercising his authority. An extremely, friendly, Christianname spirit prevails among all levels of employee. An indication was a list of. drivers' telephone numbers I noticed on Mr. Ives' desk. This noted "Joe, Len, Harry, Spud," rather than, perhaps, "Green, Brown, Robinson, Jones." No driver has left the company. Drivers are paid a nightly subsistence allowance of 18s, 6d. and a daily meal allowance of Is. 6d.

Vehicle costings are based on total averages, and a pence-per-mile figure is known for each type of vehicle operated. It is frequently necessary to make journeys which are frankly wasteful from a transport aspect, but nevertheless necessary if expensive hold-ups in the factory are to be avoided. This makes the matter of costing of academic interest.

The exercise of a vehicle-maintenance programme is not incumbent upon the traffic department, but is drawn up and imposed by the works manager. Every vehicle is serviced on a Saturday and repairs and overhauls are done in the well-equipped garage according to drivers' reports and a laid-down schedule. Various machining and fabrication operations can be undertaken in the works.