Gearing for economy

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Higher final drive, speed governor or modified engine?

A WELL-KNOWN MAKER of proprietary diesel engines recently complained to me that operators of more powerful vehicles were unwilling to employ a high-ratio final drive despite its potential as a fuel saver. Their reasoning was that the resultant increase in maximum speed would be exploited by the average driver to travel at excessive speed. notably on motorways. which would increase wear and tear as well as the likelihood of serious accident.

This kind of argument has been repeated. with convictiOn, over the past 20 years or more. and it is significant that operators have had in mind road speeds at the top end of the range of 60mph plus on motorways or the equivalent rather than 40/50mph plus on cross-country routes.

Overspeed problems

The fact that ample power pays off economically if it is properly used (in conjunction with a matched transmission) in terms of fuel economy and shorter journey times closes the gap between a performance that is profitable and a performance that could increase maintenance costs as well as the risk of accidents. It is open to question at this stage whether the advent of the tachograph will eliminate over-speeding in the foreseeable future, or even discourage it to any extent.

The road-speed governor has never taken on in the UK. perhaps for the obvious reason that its use would have been resisted by drivers and their unions in the same way that fitting a tachograph has been resisted. And driver satisfaction is an all-important selling point these days. But the limit for lorries on motorways is a very fair speed at any time. and the need to intensify the operations of big vehicles to cut overall running costs will probably increaser. motorway mileages. It is mainly in this context that the value of a road-speed governor is assessed compared with, or in conjunction with, changing the form in which power is produced to limit the top speed of more powerful vehicles without impairing acceleration and

gradient ability. The latter could well provide additional benefits.

In a report of a road test of a Leyland Super Beaver equipped with an Associated Engineering road speed regulator (CM June 12 1970) it was revealed that the governor enabled fuel consumption to be improved by about 16 per cent *pen unladen and 10 per cent when laden. The 75.7km (47-mile) test route included a hilly motorway section and about 32km (20 miles) of heavily congested main roads. Maximum speed_ of the vehicle was reduced from 101km/h (63mph) to 76/ 77km/h (47/48mph) by the regulator and the average speed for • 151km (93.6 miles) from 57kmli (35. I mph) to 53km/ h (33mph). The respective fuel consumptions were 3.8km/1 ( I0.8mpg) and 4.38km/1 (12.4mpg). It was pointed out in the report that a greater improvement in fuel consumption would have been expected on all motorways running together with a bigger reduction in average speed.

In this case the top speed of the vehicle with a governor was way below the motorway limit; and the use of a regulator was obviously unacceptable commercially at that time. The price of fuel has more than doubled since then and is likely to increase, but a regulator would take a lot of selling today unless it had legislative backing. The device mentioned is no longer available.

So while a governor could play a useful part at some time in the future in the kind of application mentioned in the test report, there is no promise it would ket off the ground without a lot of pushing. But an application to a powerful heavy vehicle to limit top speed to the maximum allowed on motorways plus a reasonable margin should get support from manufacturers. operators — and perhaps. drivers and their unions.

Risk reducer

The regulator would not be used as a fuel saver — although it would probably save some fuel — but as a risk reducer and life prolonger.

Is it worth bothering about? Or will it be? Time will tell. And meanwhile a substantial number of heavy vehicles

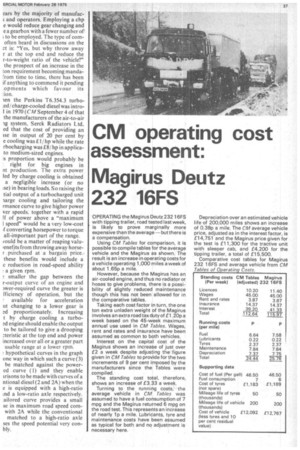

In this graph of hypothetical c% shown the power required to p vehicle (1) the relative positions a put curve of a conventional dies high-ratio back axle and with a low. (2 and 2A respectively) and the ou. uprated engine of the so-called horsepower type (3).

operate a lot of the time with th running at higher-than-optimt because the overall top-gear rat low. To the manufacturer tryin the idea that more power r economically, the overspeedi with a high gear is a major prc

Not many years ago, before crisis, the conventional dies regarded by pipe-dreamers an leading technicians as a wastii that would give way to more s cated lightweight units such as turbine and rotary engine. The ft has extended diesel viability i tely (until hydrocarbon fuels dr) conjunction with the more acceptibility of turbocharging to an engine designed to accom high cylinder pressures, it ha impetus to research projects a tailoring performance in wa: could be welcomed by the hgv The operator who wants powe right place combined with econc durability would also benefit.

The driver appeal of a equipped with a constant-hors diesel has not been taken seriou ears by the majority of manufac and operators. Employing a chp e would reduce gear changing and e a gearbox with a fewer number of ; to be employed. The type of cornoften heard in discussions on the ct is: "Yes. but why throw away r at the top end and reduce the r-to-weight ratio of the vehicle?" the prospect of an increase in the on requirement becoming manda"rom time to time. there has been if anything to commend it pending opments which favour its len the Perkins T6.354.3 turbo:ed/charge-cooled diesel was intro1 in 1970 (CAI September 4 of that the manufacturers of the air-to-air ig system. Serck Radiators Ltd. ed that the cost of providing an ise in output of 20 per cent by e cooling was £1/ hp while the rate rbocharging was £8/ hp in applicato medium-sized engines.

Ls proportion would probably be right for big engines in nt production. The extra power led by charge cooling is obtained a negligible increase (or no Ise) in bearing loads. So raising the tial output of a turbocharged unit large cooling and tailoring the rmance curve to give higher power ver speeds; together with a rapid 11 of power above a "maximum I speed" would be a very low-cost 4 converting horsepower to torque all-important part of the range. ifould be a matter of reaping valuienefits from throwing away horse purchased at a bargain price.'

these benefits would include a c reduction in road-speed ability a given rpm.

smaller the gap between the r-output curve of an engine and )wer-required curve the greater is fficiency of operation. but the • available for acceleration ut changing to a lower gear is ;A proportionately. increasing t by charge cooling a turbo ed should enable the output to be tailored to give a drooping cteristic at the top end and power increased over all or a greater part usable range at a lower rpm.

hypothetical curves in the graph one way in which such a curve (3) be matched against the powered curve ( I) and they enable irisons to be made with curves of a ntional diesel (2 and 2A) when the e is equipped with a high-ratio tnd a low-ratio axle respectively. ailored curve provides a small se in maximum road speed cornwith 2A while the conventional matched to a high-ratio axle ses the speed potential very conbly.