Reginald Holmes Wilson

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

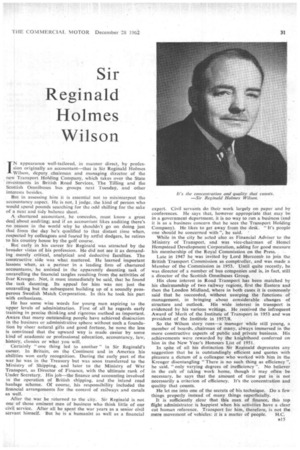

IN appearance well-tailored, in manner direct, by profession originally an accountant—that is Sir Reginald Holmes Wilson, deputy chairman and managing director of the new Transport Holding Company, which takes over the State ' investments in British Road Services, The Tilling and the Scottish Omnibuses bus groups next Tuesday, and other interests besides.

But in assessing him it is essential not to misinterpret the accountancy aspect. He is not, I judge, the kind of person who would spend pounds searching for the odd shilling for the sake of a neat and tidy balance sheet.

A chartered accountant, he concedes, must know a great deal about auditing; and if an accountant likes auditing there's no reason in the world why he shouldn't go on doing just that from the day he's qualified to that distant time when, respected by colleagues and feared by artful dodgers, he retires to his country house by the golf course.

But early in his career Sir Reginald was attracted by the broader vistas of his profession. He did not see it as demanding merely critical, analytical and deductive faculties. The constructive side was what mattered. He learned important lessons when, as a partner in a leading firm of chartered accountants, he assisted in the apparently daunting task of unravelling the financial tangles resulting from the activities of Ivar Kreuger. Not, it must immediately be said, that he found the task daunting. Its appeal for him was not just the unravelling but the subsequent building up of a soundly prosperous Swedish Match Corporation. In this he took his part with enthusiasm. , He has some wise words for young men aspiring to the upper levels of administration. First of all he regards early training in precise thinking and rigorous method as important. Aware that many outstanding people have achieved distinction in the business or administrative sphere without such a foundation by sheer natural gifts and good fortune, he none the less is convinced that the upward way is made easier by some kind of academic or professional education, accountancy, law, history, classics or what you will.

Certainly "one thing led to another" in Sir Reginald's career. In Britain, on the Continent and in America his abilities won early recognition. During the early part of the war he was in the Treasury but was soon transferred to the Ministry of Shipping, and later to the Ministry of War Transport, as Director of Finance, with the ultimate rank of Under Secretary. His job—the finance and accounting involved in the operation of British shipping, and the inland road haulage scheme. Of course, his responsibility included the financial arrangements for the control of railways and canals as well.

After the war he returned to the city. Sir Reginald is not one of those eminent men of business who think little of our civil service. After all he spent the war years as a senior civil servant himself. But he is a humanist as well as a financial expert. Civil servants do their work largely on paper and by conferences. He says that, however appropriate that may be in a government department, it is no way to run a business (and it is as a business concern that he sees the Transport Holding Company). He likes to get away from the desk. "It's people one should be concerned with ", he said. '

While in the city he acted also as Financial Adviser to the Ministry of Transport, and was vice-chairman of Hemel Hempstead Development Corporation, adding for good measure his membership of the Royal Commission on the Press.

Late in 1947 he was invited by Lord Hurcomb to join the British Transport Commission as comptroller, and was made a Member of the Commission in 1953. Until quite recently, he was director of a number of bus companies and is, in fact, still a director of the Scottish Omnibuses Group.

His close interest in Road Transport has been matched by his chairmanship of two railway regions, first the Eastern and then the London Midland, where in both cases it is commonly said that he succeeded, without usurping the functions of management, in bringing about considerable changes of structure and outlook. His wide interest in tra-nsport is evidenced by his various writings. He received the infrequent Award of Merit of the Institute of Transport in 1953 and was president of the Institute in 1957/8.

So the Wilson story runs—a manager while still young, a member of boards, chairman of many, always immersed in the more constructive aspects of public and private business. His achievements were rewarded by the knighthood conferred on him in the New Year's Honours List of 1951.

In spite of all his distinction Sir Reginald deprecates any suggestion that he is outstandingly efficient and quotes with pleasure a dictum of a colleague who worked with him in the Kreuger disentangling "There is no such thing as efficiency ", he said, "only varying degrees of inefficiency ". No believer in the cult of taking work home, though it may often be necessary, he says that the amount of time put in is not necessarily a criterion of efficiency. It's the concentration and quality that counts.

He let me into one of the secrets of his technique. Do a few things properly instead of many things superficially.

It is sufficiently olear that this man of finance, this top flight administrator is happiest when his activities have a clear cut human reference. Transport for him, therefore, is not the mere movement of vehicles: it is a matter of people. H.C.