THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE.

Page 18

Page 19

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A Serious Competitor with the Horse : Its Possibilities and Limitations.

T IS MERELY in accordance with the way of the world that increasing and livelier interest should

• be manifested at this moment in the electricallypropelled vehicle, as a possible contribution to the solution of the searching and complex problems assooiated with prompt and economic road transportation. The rising bog of liquid fuels; the scarcity of labour, and the lack of alternative means of transportation have compelled greater attention to be centred upon this medium of propulsion. Not that the electric commercial car has been standing still during the past few years. . Far from it. Whereas in 1914 there were only 150 vehicles of this description in service, to-day there are approximately 2000 in constant operation. At the moment demand has overtaken supply, but strenuous efforts are being made to secure an adjustment of.this issue in favour of the latter factor.

In the past the electric vehicle has not been given a square deal. Its petrol consort was accepted as being the complete remedy to all the ills to which transportation is heir. Electricity has ever been popularly regarded as a. rival to petrol propulsion. This is a grievous fallacy. Electricity, at least so far as our current knowledge carries the question, can never displace the internal-combustion engine upon the high roads, but it certainly can consummate certain phases of the work generally assigned to the petrol motor to better and cheaper advantage.

The petrol-driven vehicle, as applied to commercial operations, has never achieved sdeti a complete revolution as has its contemporary devoted to passengercarrying purposes. The private motorcar has almost driven the horse into oblivion. The streets of our cities and towns have been motorized to the extent of 97 per cent., so far as private passenger traffic is concerned. But with regard to commercial carrying traffic, a vastly different story is related: in this instance, motorization represents only 12i per cent, of the whole. The horse still holds sway. For inter-city business with long -waits the petrol

vehicle -can i

not quite displace the horse. But this s the very traffic, which the electric vehicle can handle, and B54

to such advantage as to be superior to both petrol and animal-traction from the point of economy.

En passant, it must be remembered that in all comparisons between commercial and private business it

is essential to eliminate the motorbus. That vehicle,

with its peculiar highly-specialized traffic; stands in a class by itself. One has only -to follow the move ments of one of these vehicles through the streets to observe how all .other wheeled traffic gives way -to it. The motorbus has the command of the road.

But if one takes stock of the commercial motor properly so-called—as represented by the lorry—one will see that it is the victim of overwhelming forces. The horse-drawn vehicle determines the pace of the moving volume of traffic, and as the strength of a chain is no greater than that of its weakest link, so the velocity of street traffic is governed by the pace of the slowest unit—the horse-drawn vehicle.

In the case of cities having comparatively narrow streets carrying a huge volume of traffic, this subjec tion of petrol to animal speed is strikingly pro nounced. So far as London is concerned, it is doubtful—at least in the centres where the heaviest volumes of traffic are encountered—if the mechanically-driven vehicular traffic exceeds an average of 21 miles per hour, which is approximately that of the horse.

In the face of such a low limitation, petrol traction cannot be otherwise than expensive. High speeds are of no avail because advantage cannot be taken of them. Any engine or machine is most eco nomical when maintaining ,its full rated output ; economy drops as the speed falls. Accordingly, there fore, it is incumbent to provide a vehicle having perhaps a moderate maximum speed, but possessed of high manceuvring powers, quick in acceleration, and able to take ad vantage of every opportunity which presents itself for the utilization of its highest speed. Obviously, nothing can excel the electric vehicle in this respect. Its maximum speed is relatively low, ranging, possibly, from 12-15 miles per hour in the ease of a 10-cwt. van to something in the neighbour

hood of 7 miles per hour for a 5-ton lorry. And it has been found from

comparative experience', over iden tical around, that not only is the electric vehicle able to show a higher average speed, but this speed will be maintained consistently nearer to the maximum than is the ease with its petrol consort.

So far as the street is concerned, all traffic is at the mercy of blocks stops, delays and holcLups, which, in the aggregate of the day's working, represent an appreciable span of dead or unremunerative time. In the case of the petrol vehicle wear and tear, as well as consumption of fuel, are proceeding uninterruptedly during such periods of enforced idleness. The engine is kept running, imposing demands upon fuel and lubricating oil. Engine movement,even when throttled down, is contributing its quota to the item of depreciation through vibration and the persistent movement of certain parts. But in the case of the electric vehicle, everything is reduced to a condition of quiescence during such periods. The current is shut off, lubrication ceases, or nearly so, while vibration is absent because all moving parts are at rest.

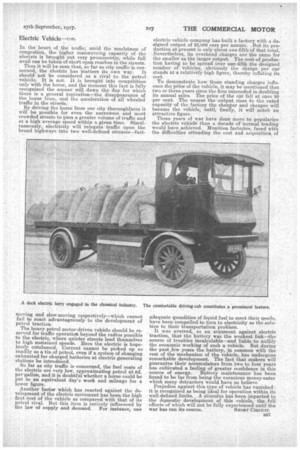

In the heart of the traffic; amid the maelstrom of congestion, the higher manceuvring capacity of the electric is brought out very prominently, while full avail can be taken of short open reaches in the streets.

Thus it will be seen that, so far as city traffic as concerned, the electric has matters its own way. It should not be considered as a rival to the petrol Vehicle. It is not. It is brought into competition only with the horse, and the moment this fact is fully recognized the sooner will dawn the day for which there is a general aspiration—the disappearance of the horse from, and the acceleration of all wheeled traffic m the streets.

By driving the horse from our city thoroughfares it will be possible for even the narrowest and most crowded streets to pass a greater volume of traffic and at a high average speed within a given time. Simultaneously, electricity will -relegate traffic upon the broad highways into two well-defined streams—fast

moving and slow-moving respectively—which cannot fail to react advantageously to the development of petrol traction.

The heavy petrol motor-driven vehicle should be reserved for traffic operatioti beyond the radius possible to the electric, where quieter streets lend themselves to high sustained speeds. Here the electric is hopelessly outclassed. Current cannot be picked up so readily as a tin of petrol, even if a system of changing exhausted for charged batteries at electric generating stations be introduced.

So far as city traffic is concerned, the fuel costs of the electric are very, low, approximating petrol at 6d. per gallon, and it is doubtful whether a horse could be put to an equivalent day's work and mileage for a lower figure.

Another factor which bas reacted against the development of the electric movement has been the high first cost of the vehicle as compared with that of its petrol rival. But this item is entirely influenced by the law of supply and demand. For instance, one electric vehicle company has built a factory with a designed output of 25,000 cars per annum. But its production at present is only about one-fifth of that total. Nevertheless, its overhead charges are the same for the smaller as the larger output. The cost of production having to be spread over one-fifth the designed number of vehicles, obviously the charge per car stands at a relatively high figure, thereby inflating its cost.

To demonstrate how these standing charges influence the price of the vehicle, it may be mentioned that two or three years since the firm succeeded in doubling its annual sales. The price of the car fell at once 20 per cent. The nearer the output rises to the rated capacity of the factory the cheaper and cheaper will become the vehicle, until, finally, it will notch an attractive figure. Three years of war have done more to popularize the electric vehicle than a decade of normal trading would have achieved. Munition factories, faced with the difficulties attending the cost and acquisition of adequate quantities of liquid fuel to meet their needs, have been compelled to turn to electricity as the solution to their transportation problem. It was averred, as an argument against electric traction, that the battery was the weakest link—the source of troubles incalculable—and liable to nullify the economic working of such a vehicle. But during the past „few years the battery, in common with the rest of the mechanism of the vehicle, has undergone remarkable development. The fact that makers will guarantee their accumulators from two to four years has cultivated a feeling of greater confidence in this source of energy. Battery maintenance has been found to be far from being the voracious money-eater which many detractors would have us believe. Prejudice against this type of vehicle has vanished : it is recognized as being ideal for operation within its well-defined limits. A stimulus has been imparted to the domestic development of this vehicle, the full effects of which will not be fully experienced until the

war has run its course. SHORT CIRCUIT.