GETTING GOOD RETURNS for

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

'.-CAL7 LIVESTOCK HAULAGE

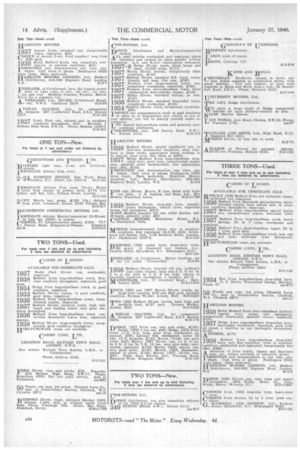

A Suggested Schedule of Rates for Local Haulage of Livestock with a Definite Minimum Figure THE table which accompanies this article is reproduced from the issue of The Commercial Motor dated January 13.It is, in effect, the outcome of an attempt to fix a schedule of charges for the conveyance of livestock, up to and including a radius of 20 miles.

It will be recalled that, in a previous article, I pointed out the impracticability of applying direct calculation, of cost of transit, plus profit, in arriving at rates for this class of work. I showed how, if that method were applied and carried to its logical conclusion, absurd and impossible figures resulted. This table is designed with that factor in view. It is not " all my own work," for I have had considerable assistance, in compiling it, from an experienced haulier who specializes in this class of work.

There are several things about this table which are of interest. The first was mentioned in the concluding paragraph of the previous article, namely, that there is a minimum figure, below which the haulier will not convey any description, or number, of livestock. That minimum is shown quite clearly, in the table, to be 6s. and for that amount one beast, 10 sheep or one cow and calf will be conveyed any distance up to 20 miles.

The second point about the table, which will strike the reader as curious, is the prevalence of blank spaces. They are to he interpreted as meaning that there is no additional charge, over and above that last quoted along the horizontal line in which the blanks appear, for conveying additional head of livestock.

For example, 6s. is the price for conveying one or two head of livestock over a five-mile lead and that charge remains the same even if the farmer loads the vehicle with as many as seven beasts or 70 sheep. Or again, 15s. is the charge for carrying five beasts for a distance of 10 or 11 miles and there will be no addition to that if the farmer puts six or seven beasts on the lorry.

The figures in the last column of the first half of the table, and the last column of the second half, apply to a larger type of vehicle which is needed to .carry the loads specified. For the conveyance of eight beasts, seven cows and calves or 80 sheep, a vehicle of 20-ft. body-length is required and an increased charge is necessary on that account.

In considering this schedule of charges, it must be kept in mind that profit at• the rates quoted is possible only in the case of those hauliers who have sufficient business acumen and knowledge of their trade and who give such service as to make it likely that in any morning they will pick up not one but several beasts, for conveyance over these short leads.

Going to extremes, but, nevertheless, exemplifying the sort of thing that livestock hauliers have to bear in mind, in relation to these schedules of rates, take the case of a parcels-carrying business in which it is possible to have a small parcel carried a considerable distance for 4d. or 6d.

The parcels carrier is like the livestock haulier, to this extent at any rate, that he runs a regular service. He relies upon collecting sufficient parcels to make that service pay at the rates quoted. The rates themselves are actually fixed more by competition than on any basis of cost and profit, and are the best that can be obtained. It is only by ensuring a sufficiency of traffic that they can be made profitable.

As showing the potentialities of these rates, the follow ing, which is a description of an attual day's work with a livestack haulierhaulier's vehicle, a 3-tanner, is of interest.

First we must consider what I call the outward journeys—those which take place in the morning when the vehicle leaves the haulier's headquarters and goes here and there, picking up stock for the market.

This vehicle actually made three journeys in that way during the morning. In the course of the first journey it visited three farms. At the first farm, it picked up one cow and calf for conveyance to a market six miles distant, then, at another farm, it picked up another cow and calf for conveyance to a market five miles distant. In both cases, assuming that payment was made on the basis quoted in the table, the remuneration would be 6s. The actual distance travelled was 13 miles.

The second journey was to a farm only three miles from the market, and there 40 sheep were picked up and delivered to that market. The total distance covered was six miles and the remuneration, again according to the table, was 6s.

On the third journey, six beasts were picked up and conveyed to a market eight miles from the farm; the total distance travelled was 16 miles and the revenue, again according to the table, was 12s.

Summarizing the foregoing, the vehicle covered 35 miles and was occupied, in all, 41 hours in picking up the animals, travelling, and setting them down at the market. The total revenue was £1 8s.

Now, I must deal with what I call the inward journey, which is the work done in the afternoon, when the livestock in the market have been sold and the haulier is called upon to deliver them from the market to the abattoirs, to other farms or to grazing land on account of cattle dealers.

In the course of the first journey, five beasts, 16 sheep and two calves were conveyed a distance of six miles, all to the instructions of one customer. That means that there was, in effect, one pick-up of these 23 animals at the market and one delivery at the abattoir. The price for this, according to schedule, is the maximum for a six-mile run; that is to say, Ss. 6d. The actual mileage covered was 12. That would be going from the market to the point of delivery and returning for the second load. • On the second journey, three beasts are carted from the market to an abattoir in the same town, the nominal distance being half a mile; the charge is 6s. and the actual distance travelled, one mile.

For the third and final journey that day, four beasts are taken from the market to a point three miles away, the vehicle earning 6s, and actually travelling seven miles. In the afternoon the sum total -of earnings is :£.1 Os. 6d., the distance travelled 20 miles, and the time occupied in collecting, delivering and travelling, hours. In addition, there was a wait of 31 hours at the market, as between making the last morning delivery and beginning to collect for the first afternoon journey.

The sum total of the day's work thus comprises 10-i hours in point of time and 5S miles' running, and the revenue is £2 Ss. 6d.

That is ahmost exactly loid. per mile run, which compares quite reasonably with what should be earned according to the table published on page 658 of the issue of The Commercial Motor for December 30. It was shown that a vehicle operating 400 miles per week must earn at least 9-id. per mile run, in order to show a reasonable profit. This machine is not running that mileage and the extra penny is approximately sufficient to provide for the deficiency in weekly mileage and, on the whole, it may be said that the rates set out in the table which accompanies this article do, so far as this example is concerned, give the chance to make a reasonable profit.

In a subsequent article I shall take further examples and check them against this table, further to prove, as I think is the case, that these figures meet the requirements of livestock haulage over the distances quoted.