GEAR CHANGING ON GATE-CHANGE VEHICLES.

Page 10

Page 11

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Clean Gear Changing an Important Factor in Reducing Maintenance Costs. The Usefulness of the Clutch Stop.

AUTOMOBILES have been in constant daily use on the road for such a long time, and the gate change has so long been accepted as being quite ordinary practice, that it would seem, at first sight, that anyone concerned with lorries would he so

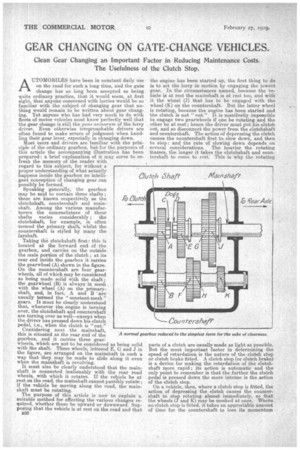

familiar with the subject of changing gear that no thing would remain to be written about gear changing. Yet anyone who has had very much to do with fleets of motor vehicles must know perfectly well that the gear change is still the pons asinorunt of the lorry driver. Even otherwise irreproachable drivers are often found to make errors of judgment when handling their gear lever, especially in changing down. Most users and drivers are familiar with the principle of the ordinary gearbox, but for the purposes of this article the accompanying illustration has been prepared : a brief explanation of it may serve to refresh the memory of the reader with regard to this subject, for without a proper understanding of what actually happens inside the gearbox no intelligent conception of changing gear can possibly be formed.

Speaking generally, the gearbox may be said to contain three shafts ; these are known respectively as the dutchshaft, countershaft and mainshaft. Among the various manufacturers the nomenclature of these shafts varies considerably ; the elutchahatt, for example, is often termed the primary shaft, whilst the countershaft is styled by many the layshaft.

Taking the clutchshaft first: this is located at the forward end of the gearbox, and carries on the outside the male portion of the clutch ; at its rear end inside the gearbox it carries the gearwheel (A) shown in the figure. On the countershaft are four gearwheels, all of which may be considered as being made solid with the shaft ; the gearwheel (B) is always in mesh. with the wheel (A) on the primaryshaft, and, in fact, A and B are usually termed the "constant-mesh" gears. It must be clearly understood that, whenever the engine is turning over, the clutchshaft and countershaft are turning over as well—except when the driver nets pressed down his clutch pedal, i.e., when the clutch is "out."

ConSidering next the mainshaft, this is situated at the rear end of the gearbox, and it carries three gear wheels which are not to be considered as being solid with tile shaft. These wheels, lettered E, G and J in the figure, are arranged on the mainshaft in such a way that they may be made to slide along it even when the mainshaft is revolving. It must also be clearly understood that the mainshaft is connected inalienably with the rear road wheels, with which it rotates. If the vehicle be at rest on the road, the mainshaft cannot possibly rotate : if the vehicle be moving along the road, the mainshaft must be rotating. The purpose of this article is now to explain a suitable method for effecting the various changes required, whether these be upward or downward. Supposing that the vehicle is at rest on the road and that

the engine has been started up, the first thing to do is to set the lorry in motion by engaging the lowest gear. In the circumstances named, because the vehicleis at rest the mainshaft is at rest too, and with it the wheel (3-) that has to be engaged with the wheel (K) on the countershaft. But the latter wheel is rotating, because the engine has been started and the clutch is not "out." It is manifestly impossible te engage two gearwheels if one be rotating and the other be at rest ; hence the driver must put his clutch out, and so disconnect the power from the dutchshaft and countershaft. The action of depressing the clutch causes the countershaft first to slow down, and then to stop : and the rate of slowing down depends on several considerations. The heavier the rotating masses, the longer it takes the clutchshaft and countershaft to come to rest. This is why the rotating

parts of a clutch are usually made as light as possible. But the most important factor in determining the speed of retardation is the nature of the clutch stop or clutch brake fitted. A clutch stop (or clutch brake) is a device for making the retardation of the clutchshaft more rapid ; its action is automatic and the only point to remember is that the further the clutch pedal is pressed down the more intense is the action of the clutch stop. On a vehicle, then, where a clutch stop is fitted, the action of depressing the clutch causes the countershaft to stop rotating almost immediately, so that the wheels (J and K) may be meshed at once. Where no clutch stop is fitted, it takes an appreciable amount of time for the countershaft to lose its momentum sufficiently to come to a standstill ; often the driver has to wait three or four seconds before he can engage his first gear and so start the lorry.

The lorry having been caused to move off in first gear, it becomes necessary to change from the first into the second speed, i.e., to change "up." Because this operation has to be effected when the vehicle is on the move, it is evident that wheels (H and G) must be meshed when both are rotating. To do this, one essential condition must be fulfilled, which is, that the tooth speeds of the two wheels shall be the same. But, during first gear running, because wheel (H) is greater than wheel (K), its tooth speed must be greater than that of wheel (K), since the two have the same r.p.m.. due to their both being solid with the countershaft. Also wheel (J) has a greater tooth speed than wheel (G), for a similar reason. Again, since J and K are in mesh, their tooth speeds must be equal. It follows from this that the tooth speed of wheel (H) is higher than that of wheel (G); but these are the two gearwheels that have to be meshed. Hence it follows that, in the action of changing up, the revolution speed of the countershaft has to be reduced so as to bring the tooth speed of wheel (}1) down to that of wheel (G). This is done by depressing the clutch pedal sufficiently to bring about the necessary slowing-down of the countershaft: evidently the countershaft must not be slowed down too much, otherwise it will be necessary to re-engage the clutch and then declutch again.

The procedure of changing up may, therefore, be summarized as follows :—Depress the clutch as far as it will go, at the same time place the gear lever in the neutral position ; then, still keeping the clutch pressed down, gently insinuate the lever towards its final position and thrust it right home as soon as no resistance is encountered. Needless to say, this feeling-in " requires a very delicate touch ; with practice it becomes second nature.

To the reader who has followed the foregoing explanation of changing up, it now becomes clear why it is advantageous to have a clutch stop on the lorry. Supposing that a lorry with no clutch stop has to be started from rest on a road that has a slight upward inclination, 'an ascent that is not steep enough to warrant continuance in the lowest gear. What happens is this : the vehicle, having been moved in low gear, soon attains sufficient speed to warrant an upward change: the driver throws out his clutch, places his gear lever in neutral, and waits for the time when the countershaft shall have slowed down sufficiently. But while he is waiting, the extra resistance at the road wheels due to the upward inclination of the road exercises a retarding effect on the mainshaft, so that by the time the countershaft has a sufficiently reduced speed the mainshaft also will have slowed down, or even come to a standstill.

One make of foreign lorry used extensively by the British Expeditionary Force suffered from this defect of not having a clutch stop ; between second and third gears a pause of five seconds was necessary. There are few drivers, however, who seem inclined to make so long a pause, and the result was that the gears on this make of lorry suffered fairly rough handling. In lustice to the makers, however, it should be added that the gearwheels were made of such excellent material that they did not suffer so much as might have been anticipated.

The crux of the whole situation in changing up is simply a question of time : how long must one pause with the gear in neutral and the clutch pedal depressed ? The answer to this question can only be supplied by experience, since there is no uniformity in the length of pause necessary for various makes of vehicle, or even for two vehicles of the same make and type where there is a difference in the extent to which the clutch stop has worn. Another factor to be remembered is that a proper upward change cannot be effected except the engine be running properly. If, for any reason, the engine cannot be made to tick over very slowly. S, proper upward change becomes almost impossible. Changing down presents a rather different problem. Referring again to the figure, if it be desired to change down from second to first speed, it means that G and H have to be unmeshed and J and K meshed. In second speed, since G and H are in mesh, their tooth speeds are of necessity equal ; but the tooth speed of G is less than that of J, and the tooth speed of H is greater than. that of K. Much less, therefore, is the tooth speed of K than of J; but these are the two wheels that have to be meshed in the operation of changing down. This operation, therefore, must be performed in such a way as to increase the revolution speed of the countershaft while the gears are in neutral.

The procedure of changing-down may, therefore, be summarized as follows :—Slightly depress the elutch pedal (not sufficiently to bring the clutch stop into action, but merely enough to relieve the teeth of the gearwheels from the transmission of power during the operation of the gear lever). Immediately the clutch has thus been slightly depressed, put the gear lever into the neutral position, at the same time letting in the clutch again. Accelerate the engine to an extent dependent partly on the speed of the vehicle, and partly on the difference between the two gear ratios concerned. When the engine has been accelerated sufficiently, slightly depress the clutch pedal and gently insinuate the gear lever towards its new position, pushing it home when no further resistance is felt.

In actual practice, this operation takes far less time to effect than it takes to explain ; a practised driver can easily accomplish the operation. of changing down subconsciously, since it very soon becomes a matter of habit rather than of thought. The great question is, how much must the engine be accelerated when the clutch pedal is not depressed and the gear lever is in neutral? Evidently, the faster the vehicle is travelling along the road, the more acceleration will have to be given' if the vehicle be travelling very slowly, the amount of acceleration is almost nil. Care must be taken, in changing down, not to depress the clutch pedal to its fullest extent, otherwise the clutch stop will come into action and probably spoil the change.

All of the foregoing has been written rather with the view of explaining the principles that enter into the operation of changing gear, rather than of laying down dogmatically a series of "Thou shahs" and " Thou shalt mats." Any driver of average intelligence, provided that he understands what is happening in the gearbox, should very soon acquire the skill necessary to effect a quiet change under any circumstances. That this skill is Worth acquiring seems selfevident ; yet the fact remains that in gearbox after gearbox brought into almost any repairer's garage, the teeth of the gearwheels are more or less stripped— the result of bad changing. Proper attention to the question of handling the gear lever means a diminished repair bill it also means that driving will, in itself, be more agreeable and more pleasant by reason of the absence of the hideous noise produced by grinding gears. It should be pointed out that the methods above described are not the only theoretically perfect and practically expedient ones, although all other proper methods differ from the foregoing ones only in detail. An example of this variation in detail is to be found in the double-clutching method of changing down usually practised in the M.T. A.S.C. With this method the driver is expected to have learnt, by experience or ,othervsise, exactly how much acceleration 18 necessary to be given under any set of conditions, and the operation of "feeling-in" is not considered necessary.