W/o-pedal transport at 32 tom

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Gibb Grace CEng, DAnE, MtMechE Pictures by Dick Ross

GKN-SRM fully automatic transmission takes the hard work out of heavy truck driving

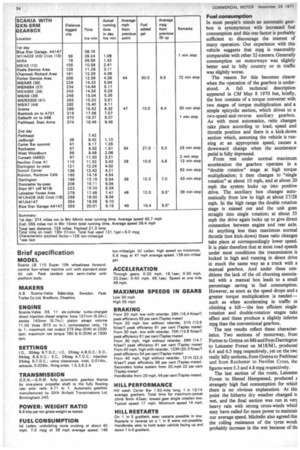

FULLY automatic transmission for heavy trucks is always just around the corner it seems, to judge from the number of times this major advance in driving ease has been aired. One of the most promising and long-developed automatic transmissions designed with heavy vehicles in mind is the SRM-GKN which GKN Birfield Transmissions Ltd, Chester Road, Erdington, Birmingham 24, has developed under licence from the Swedish SRM company, adding a two-speed auxiliary section to the existing three-speed torque converter/ epicyclic unit.

We described the box in CM on May 8 last year, and had driven a vehicle equipped with an earlier version as long ago as 1965. Recently we were given the chance of sampling the latest model over the route normally used for our full road tests, this time fitted in a Scania LB 110 coupled to a Peak semi-trailer and running at 32 tons gross weight. The results were impressive, especially from the driver's viewpoint, and with the growing emphasis on driver comfort and quality vehicles, it seems an option which may attract attention from fleet users.

Although the Scania LB 110 is an impressively big vehicle, and has 275 bhp and 780 lb ft torque available from its turbocharged engine, there is little impression of exceptional size and power once one is settled in the driving scat. The steering wheel feels relatively small for a truck, he instruments are gathered neatly before the driver and once on the move the engine tote is subdued to a low hiss. The autonatic gearbox makes gearchanging an ;ffortless business, and with only acceleraor and brake pedals to operate, there is no vork for the left foot. After the usual few rules to get to know the characteristics of he vehicle one can sit back and enjoy the lrive.

The GKN-SRM gearbox is uncannily ;ood and creates confidence right from the tart. Although we were not subjecting the 'chicle to our full road test but were more oncerned with recording the effects of the .utomatic transmission, we nevertheless sed our normal operational trial route to cotland and back, providing a basis for omparison. Since our normal tests on this pute are chiefly concerned with showing tng-distance truck performance, the route deliberately avoids most urban areas. In reality, nearly all trunk runs begin and end with a crawl out of and in to an urban area and I think that on this occasion a run from, say, London Docks through the City up to MI via Islington and Archway would have been a better test of the automatic. In the event, the light traffic we did meet on A5 was sufficient to show the tremendous advantages of the automatic from the driving point of view.

To pull away from rest the driver merely selects "automatic" on the quadrant, releases the handbrake and opens the throttle. The gearbox automatically changes gear as the road speed increases and decreases, without more ado. (One can select "low" on the quadrant, for braking effect or where the conditions make it desirable.) On tests I normally take over from the works driver at the end of the first M1 section as we pull on to the AS and within five minutes or so of taking control of a strange vehicle I am faced with a very steep hill which brings the average 32-tonner down to second or third gear and 5 or 6 mph—and if it is a strange gearbox this hill is sometimes faced with a little apprehension. With the Scania, however, after taking the middle lane to avoid being baulked I merely drove at the hill and let the gearbox sort it out. The Seattle cruised unhesitatingly over the top without any help from me.

Before the end of the AS section it became very clear that an automatic box brings a new way of life for the truck driver. It completely eliminates the mental strain of assessing the situation ahead, planning the gearchanges and the physical effort of actually making them. Roundabouts could be approached correctly with no temptation to the pushy driver to force entry in order to maintain speed. The safety aspect of the gearbox must be considerable, for one has more time to check and double check mirrors and road position at hazards, because the gearchanging function is removed completely. At roundabouts also the ZF power steering proved to be light and precise and enhanced the feeling of good driving.

At its cruising speed of 2,200 rpm or 55 mph the Scania is quiet enough to hold a normal conversation across the cab or to listen to the radio. The steering is precise, unaffected by road irregularities and vibration free. The ride is not as good as one might expect but none the less good by average standards. There is a fair amount of pull-and-push between tractive unit and trailer and thus progress is not as smooth as it might be. But on motorways the ride was perfectly acceptable. Fuel consumption In most people's minds an automatic gearbox is synonymous with increased fuel consumption and this one factor is probably sufficient to discourage the interest of many operators. Our experience with this vehicle suggests that mpg is reasonably comparable with other 32-tanners. Generally consumption on motorways was slightly better and in hilly country or in traffic was slightly worse.

The reason for this becomes clearer when the operation of the gearbox is understood. A full technical description appeared in CM May 8 1970 but, briefly, the box consists of a torque converter with two stages of torque multiplication and a simple epicyclic section, which drives to a two-speed-and-reverse auxiliary gearbox. As with most automatics, ratio changes take place according to load, speed and throttle position and there is a kick-down section which, assuming the vehicle is running at an appropriate speed, causes a downward change when the accelerator pedal is fully depressed.

From rest under normal maximum acceleration the gearbox operates in a "double rotation" stage at high torque multiplication; it then changes to "single rotation" at about 10 mph, and at about 20 mph the system locks up into positive drive. The auxiliary box changes automatically from low to high at about 27/28 mph. In the high range the double rotation stage is missed out and the unit goes straight into single rotation; at about 35 mph the drive again locks up to give direct connection between engine and rear axle. At anything less than maximum normal throttle (not kick-down) these ratio changes take place at correspondingly lower speed. It is plain therefore that at most road speeds under most conditions the transmission is locked in high and running in direct drive in much the same way as a truck with a manual gearbox. And under these conditions the lack of the oil churning associated with a manual box leads to a small percentage saving in fuel consumption. However, as soon as the speed drops and a greater torque multiplication is neededsuch as when accelerating in traffic or climbing a hill-the less efficient singlerotation and double-rotation stages takt effect and these produce a slightly inferioi mpg than the conventional gearbox.

The test results reflect these characteristics. Two sections of motorway, from Forton to Gretna on M6 and from Darringtor to Leicester Forest on M18/M1, produced 6.4 and 6.5 mpg respectively, yet on the twc really hilly sections, from Gretna to Pathhead and from Rochester to Nevilles Cross, the figures were 5.3 and 4.8 mpg respectively.

The last section of the route, Leicestei Forest to Hemel Hempstead, produced E strangely high fuel consumption for whict there is no obvious explanation. At thif point the hitherto dry weather changed tr wet, and the final section was run in ver3 heavy rain with strong cross-winds whicl may have called for more power to maintair our average speed. Michelin also agreed tha the rolling resistance of the tyres wouk probably increase in the wet because of Om

pumping effect of the tread in dealing with the surface water.

The sharply increased consumption over this last section brought the overall average for the route down from 6.1 to 6.0 mpg, and both these figures are below the 6.2/6.5 mpg which is normal for 32-tonners. A CM test of the LB 110 running at 38 tons gave an overall of 5.7 mpg, identical with the figure produced by the Mercedes LPS 2024 running at this same gross weight.

Gradability

On motorways the Scania ran happily locked up in high ratio. On the northern leg the transmission never dropped even to single rotation high, and on the southern leg only the Leicester Forest "slow lorries" climb forced a downward change — this steep motorway section brought us down to 21 mph in low single rotation. The huge torque capacity of the Scania DS1 I engine, available down to 1300 rpm, enabled very good averages to be maintained in spite of a top speed of only 55 mph.

It is, I think, vital that a trunker should be geared to run at 55 to 60 mph on the level with the amount of motorway now open, as the time saving on a long run can be considerable. The vehicle was fitted with a 4.71:1 rear axle and was running on 10.00 x 20.00 tyres; an optional axle of 4.38:1 or even 11.00 x 20.00 tyres would improve the top speed.

The three main hills on the route were all climbed in record time for a 32-tonner. Carter Bar was climbed in 6 mm 43 sec—the same time as for the 24-ton Ford DA 2418. Riding Mill was climbed in 4 min dead — over a minute quicker than normal, and Castleside was climbed in 4 min 15 sec, again about 1 mm faster than usual. The reason for the good climbing is obviously in the first instance the very good power to weight ratio — 8.6 lhp/ton laden — but also the transmission which made the very best use of the availIble power at all times. It was interesting, (nowing these hills fairly well, to note where .he changes in the box were made and to ;heck the speed at various points in the climb. At the top of a climb the vehicle recovered its speed very quickly —in contrast to a manual-gearbox vehicle where the driver tends to "take a breather" after a hard climb.

Braking A feature of the SRM system is that an auxiliary braking effect is included in the basic design — a hydraulic retarder, in which the converter automatically locks up to give engine braking when the accelerator pedal is released. It significantly improves braking performance, and on the test vehicle its capabilities could be more precisely evaluated because the retarder could be operated by a hand lever.

On steep downgrades on motorways the retarder alone was sufficient to hold the vehicle to 60 mph. On a steep descent before Carter Bar at 40 mph the retarder held the speed constant without use of the brakes and on the steep 1 in 8 descent into west Woodburn we changed down into low and, using the retarder only, held the vehicle to 30 mph with only occasional touches on the footbrake.

The only limitation on this braking effect is the amount of cooling capacity available, for the churning of the blading which provides the braking produces a lot of heat. This heat is dissipated by a heat exchanger which taps into the engine cooling system itself. The heat exchanger is quite a small, efficient unit and the limitation is imposed by the cooling of the vehicle. Using the standard cooling system of the Scania the oil temperature in the retarder did not go above 140 deg C even on the longest downgrades. Over the life of the vehicle the saving in brake linings would be significant.

At MIRA this extra braking effect showed up as an improvement of 3 ft at 20 mph and 12 ft at 40 mph but at 30 mph no advantage was revealed. It seems that at this speed the transmission is in high and the braking effect of the retarder at its minimum. As the speed is reduced due to braking, the box does change down in the normal way but not fast enough to show the benefit. It should perhaps be emphasized that at all times, regardless of which stage the transmission is in, the act of lifting the foot from the accelerator locks up the transmission so that full engine braking is available in the normal way.

In conclusion, one can compare automatic transmission with other technological improvements such as electronic braking inasmuch as the hardware has been developed to a point where it is not only acceptable but desirable. Yet the impetus to get such a device generally accepted rests with operators. To make the unit available at a price which the operator will pay, high production numbers must be assured.

Vehicles at 32 tons and engines at 750 lb.ft torque may be an arguable case for automatics but if and when gross weights go up to 42 tons and engines go up 1000 lb.ft torque the problem begins to resolve itself, for at these weights and powers conventional transmissions can become very heavy and expensive. The torque converter also protects the valuable engine and axle against misuse and the retarder adds an important safety factor by providing extra braking. The automatic transmission begins to look very much like the right answer.