Two Conflicting Policies in Maintenance

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

N0 breakdown lorry is kept at the Kermanshah Petroleum Co.'s garage in North-western Iran, although vehicles based on this depot operate on round trips of up to 1,900 miles across the mountains. Preventive maintenance and immediate action on drivers' reports are safeguards against failure of vehicles in this area.

There is the rare occasion in winter lorry skids off the road and rolls down side, but even this causes no disturbance to the workshop routine. Two fitters are sent to the casualty by the next vehicle passing that way to strip the lorry or tanker to the component stage. Local labour is enrolled to carry the parts back to the road and assist in their reassembly. It has been known for one of these vehicles to be driven back to the depot power after a roadside rehabilitation.

The Kermanshah fleet is mainly composed of Leyland T.C.9 and Hippo oil tankers and a few International tankers. Bedford and Commer 5-tonners are employed on stores deliveries to outlying areas, but because of road conditions normally carry a 3-ton payload. Mr. D. Phillips, the garage engineer, outlined to me some of the "local deliveries" of the stores lorries, the longest run being to Meshed, a round trip of 1,885 miles. Other journeys include Shiraz, 1,400 miles; Isfahan, 790 miles; and Teheran, 710 miles. The oil tankers. carrying 2,750 gallons of fuel, distribute their loads up to 600 miles away from base.

When any of these vehicles returns to base, it is thickly coated with mud or dust, according to the season. While it is being washed, the driver is answering questions regarding its mechanical condition, and his answers are written in English on the questionnaire report. This time when a the mountain under its own report is attached to the vehicle as it is driven from the washing bay.

Because of the high standard of preventive maintenance there is usually little servicing to be done. Should there be no adjustments required, the lorry is driven on a ramp to be greased, oil levels checked and chassis inspected for spring fracture or other failure which might have escaped the notice of the driver.

After negotiating several hundred miles of boulderstrewn and pot-holed roads, the front track may have become out of adjustment, and this item is checked at the end of every journey. Likewise the tyres take heavy punishment, and they are given a thorough inspection for possible damage. Endof-journey service can be completed in 20 hours, and vehicles arriving at the depot in the early afternoon are serviced, refuelled, loaded and dispatched the same day.

There are no laws regarding the number of hours of driving that can be done in a day, and the crews are content to start their journeys at almost any time. Their bedding is carried on the cab roof and they are paid a lodging allowance. Each make and type of vehicle has its maintenance schedule arranged at a definite mileage interval. For example, the Leyland Hippo is due in workshops at 50,000-kilom. (31,250-mile) intervals. It is docked at 50,000, 200,000 and 350,000 kiloms., when new standard piston rings and the additional scraper rings are fitted. The cylinder heads, injection pump and compressor are changed, and new pump couplings are fitted. All water hoses are replaced. Wheels and tyres are sent to the appropriate section, and the brake drums removed for the inspection of facings and hubs. New oil seals are fitted to the worm shafts of the fipal-drive units, and clearances checked on the worm shaft and worm wheel. The rear-spring trunnions and spring-cye pins are changed.

This may appear an expensive system to British operators, but judged by operating conditions in Iran, it is more than justified and pays dividends in preventing premature failures.

When the vehicle has reached intermediate mileages of 100,000, 250,000 and 400,000 kiloms. it is again withdrawn from service for oversize piston rings to be fitted and the brake drums and shoes replaced. This work is in addition to the normal schedule of repairs.

Complete overhaul, involving a change of all units, is scheduled to take place at 150,000 and 300.000 kiloms. The chassis is rewired and the whole vehicle repainted. I witnessed the efficiency of this maintenance system on the road, for in my travels in the north I found clean exhausts on all the oil company's lorries and saw no disabled vehicle by the roadside.

Reconditioned as New Units removed for reconditioning are thoroughly cleaned before dispatch to the overhaul sections. They are dismantled and repaired by the appropriate section, and although no defined limits of wear are laid down for scrapping, the overhauled component is of almost new standard. Reconditioning is done mainly by arc or acetylene welding.

A small blackmith's shop and a one-man foundry are sufficient to straighten brackets or make new parts for the older vehicles when new spares are not available. During my visit, starter outboards and covers were being cast and machined for the International tankers.

The machine shop, which has reasonably modern equipment, is well organized, with all machines groupe7I at an angle to the walls. Modifications have been made to adapt the older equipment to specialized tasks. The flow of work does not justify an operator to each machine, and the machinists have now been trained to be proficient in turning, grinding, milling and shaping.

Before this interchange of work was introduced, crankshaft grinding came to a halt every time the one

skilled grinder was away from duty. There are now four turners who can operate the crank grinder with proficiency. The blacksmith's shop, foundry and machine shop were of great assistance during the war in maintaining vehicles on the Aid-to-Russia convoys.

The roads and temperatures of Iran take a heavytoll of tyres, and it is only by careful inspection at the end of each journey and the high quality of rebuilding in the tyre shop at Kermanshah that tyre life has been increased from 5,000 to 25,000 miles. A census of wear taken over a year shows that a 13.00 by 20-in. tyre fitted to a Leyland TC9 tanker has an average life of 24,500 miles, and the 10,50 by 22-in, equipment of the Leyland Hippo has a life of 22,000 miles,

I was surprised to find a tyre-repair factory in such a place as Kermanshah garage, and have seen its equal for work and equipment in only one other place—the R.A.O.C. Depot at Clailwell. A British tyre technician supervises the repairs at Kermanshah, and has a staff of four, who are kept fully employed in rebuilding damaged tyres for the four main garages. It is a legend at Kermanshah that no tyre is beyond repiir until it is worn to canvas level.

Up to this point I have described the maintenance of vehicles in an area where every journey is lengthy, but an entirely different system is employed in the Abadan zone, where vehicles of light and medium classes a e mostly used, and a town is close.

Of the fleet of 3,200 units operating in Abadan, there are 100 Bedford 32-seater buses, 110 Bedford tractor units operating with semi-trailer buses, and 532 rigid and tractive -units, mostly of Bedford manufacture. Additionally, there are 260 special-purpose commercial vehicles and 682 trailers in operation.

The 32-seater staff buses, carrying an average of 30,000 passengers a day, are housed and docked at Braim garage, which is within the town area. A slightly different arrangement is made for the articulated 50seater industrial buses, which are housed and greased at one depot and docked at a nearby garage.

The industrial buses in particular have a busy and close schedule to maintain, the three peak periods being from 3.20 a.m. to 7.45 a.m., 10 a.m. to 3.30 p.m., and 8 p.m. to 1.30 a.m. These periods coincide with the shift changes at the refinery and other establishments associated with the oil company. The peak periods leave little time for maintenance during the weekday, and units have to be withdrawn from service for docking. Buses are refuelled on returning from each journey, and running adjustments are made during the short offduty periods between peaks.

The goods-carrying fleet, hauling cargo from the dockside, transporting building materials, refinery equipment and loads of all descriptions, is housed in three garages within a main docking, depot at Bawarda, which is also the garage of the heavy transport section.

Goods vehicles are refuelled daily. During this operation the level of the engine oil and the tyre pressures are checked. Battery levels are replenished at fortnightly intervals, and the lorry or trailer is withdrawn from ser ■ i:e once a month for adjustments, oiling and greasing. Oil filters are changed every three months, the date of, change being painted on the filter casing. The average I:fe of a Bedford engine fitted to a 5-tonner or tractor unit is 28,000 miles.

Apart from the normal maintenance, repairs are made only on the basis of drivers' reports, a record of the repairs to each vehicle being kept at the docking depot. Drivers' defect reports are checked by an inspector and, according to the extent of the repairs required and availability of spares, are dealt with at the earliest opportunity.

Like the buses, the goods vehicles are maintained on a unit-exchange system, the unserviceable component being sent to the Main garage, which is the reconditioned-unit stores and overhaul depot.

Components are stripped and cleaned with a steam jenny and repaired on a production line, worn parts are mostly replaced from stock.

Unit Stores Section

There was a good-sized float of units in the stores section, and except for the electrical department, there was an appearance of lack of work in most departments. "The reason given for this was that a large number of new vehicles had been introduced, which had cut repair work.

Batteries and other electrical equipment are liable to a breakdown of insulation and consequent failure in the hot season. Therefore, the electrical section has always sufficient work during the summer. One big setback to planned production or maintenance schedules in Abadan is the occasional dust storm, which descends like a fog and fills the atmosphere with fine dust.

Because of the hot climate, the workshops are mainly open, and visibility, when a dust storm starts, is reduced to a few yards. An enclosed shop would be intolerable to work in, and because of the persistence of the storms, it would not keep the dust out.

The heavier vehicles operating in the Abadan areaThornycroft Amazons, Leyland Beavers and Mack 10-tonners—are docked on a time basis at the Main garage. Most of these heavies are on specialized work, some being equipped with Coles cranes and the remainder with Rapier 2-cubic-yd. concrete mixers.

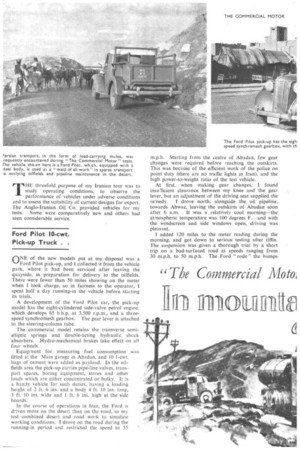

THE threefold purpose of my Iranian tour was to study operating conditions, to observe the performance of vehicles under adverse conditions ,

and to assess the suitability of current designs for export. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. provided vehicles for my tests. Some were comparatively new and others had seen considerable service. m.p.h. Starting from the centre of Abadan, few gear changes were required before reaching the outskirts. This was because of the efficient work of the police on point duty (there are no traffic lights in Iran), and the high power-to-weight ratio of the test vehicle.

At first, when making gear changes, I found insulicient clearance between my knee and the gear lever, but an adjustment of the driving seat supplied the remedy. I drove north, alongside the oil pipeline, towards Ahwaz, leaving the outskirts of Abadan soon after 6 a.m. It was a relatively cool morning—the atmospheric temperature was 100 degrees F.—and with the windscreen and side windows open, driving was pleasant.

I added 120 miles to the meter reading during the morning, and got down to serious testing after tiffiri. The suspension was given a thorough trial by a short trip on a had-surfaced road at speeds ranging from 30 m.p.h. to 50 m.p.h. The Ford "rode" the bumps As the road between Abadan and Ahwaz is level for nearly 80 miles, there is no difficulty in finding

suitable ground for acceleration or braking tests. I made these on the road, and, out of interest, took readings on the desert. When accelerating from rest, I had to control the clutch action carefully, because a rapid take-up of the transmission produced wheelspin on both road and desert. Such was the power behind the wheels.

Starting from rest, 20 m.p.h. was reached in 1.6 secs., and, using second gear, 30 m.p.h. was reached in 7.4 secs. Top-gear acceleration was equally lively, and it took 10 secs. to attain 30 m.p.h. from a rolling start of 10 m.p.h. I had thought that the high atmospheric temperature of 124 degrees F. would have dulled performance, but the behaviour of the Ford in the desert varied little from that experienced in this country. in good style without discomfort to the driver or danger to a delicate load.