ACCURACY IS

Page 45

Page 46

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BANG ON

AT THATCHAM

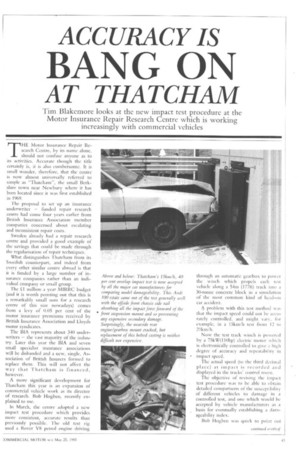

Tim Blakemore looks at the new impact test procedure at the Motor Insurance Repair Research Centre which is working increasingly with commercial vehicles

THE Motor Insurance Repair Research Centre, by its name alone, should not confuse anyone as to its activities. Accurate though the title certainly is, it is also cumbersome. It is small wonder, therefore, that the centre is now almost universally referred to simple as "Thatcham", the small Berkshire town near Newbury where it has been located since it was first established in 1969.

The proposal to set up an insurance underwriter — funded repair research centre had come four years earlier from British Insurance Association member companies concerned about escalating and inconsistent repair costs.

Sweden already had a repair research centre and provided a good example of the savings that could be made through the regularisation of repair techniques.

What distinguishes Thatcham from its Swedish counterpart, and indeed from every other similar centre abroad is that it is funded by a large number of insurance companies rather than an individual company or small group.

The U million a year MIRRC budget (and it is worth pointing out that this is a remarkably small sum for a research centre of this size nowadays) comes from a levy of 0.05 per cent of the motor insurance premiums received by British Insurance Association and Lloyds motor syndicates.

The BIA represents about 340 underwriters — the vast majority of the industry. Later this year the BIA and seven small specialist insurance associations will be disbanded and a new, single, Association of British Insurers formed to replace them. This will not affect the way that Thatcham is financed, however.

A more significant development for Thatcham this year is an expansion of commercial vehicle work as its director of research. Bob Hogben, recently explained to me.

In March, the centre adopted a new impact test procedure which provides more consistent, accurate results than previously possible. The old test rig used a Rover V8 petrol engine driving Above and below: Thatcham's 15km/h„ 40 per cent overlap impact test is now accepted by all the major car manufacturers for comparing model damageability. Thi. Audi 100 estate came out of the test generally well with the offiide front chassis side rail absorbing all the impact force JO rward of the • front suspension mount and so preventing any expensive secondary damage. Surprisingly, the nearside rear engine/gearbox mount cracked, but replacement of this bolted casting is neither difficult nor expensive. through an automatic gearbox to power the winch which propels each test vehicle along a 54m (177ft) track into a 30-tonne concrete block in a simulation of the most common kind of head-on car accident.

A problem with this test method was that the impact speed could not be accurately controlled, and might vary, for example, in a 15km/h test from 12 to 21km/h.

Now the test track winch is powered by a 75kW(110hp) electric motor which is electronically controlled to give a high degree of accuracy and repeatability in impact speed.

The actual speed (to the third decimal place) at impact is recorded and displayed. in the tracks' control room.

The objective of revising the impact test procedure was to be able to obtain detailed comparisons of the susceptibility of different vehicles to damage in a controlled test, and one which would be accepted by vehicle manufacturers as a basis for eventually establishing a damageability index.

Bob Hogben was quick to point out the difference between darnageability and repairability. He explained that car manufacturers had long ago recognised the importance of the latter, which is one reason why they willingly cooperate with Thatcham, in providing vehicles for example. And determining recommended repair times and techniques — quantifying repairability has always been an important part of Thatcham's work.

Fleet operators, private buyers, and insurance companies have recently .become increasingly concerned with how much expensive damage a low-speed impact can cause to a modern car or light commercial vehicle. Consequently the manufacturers have begun to pay more attention to their products' proneness to damage. Sonic have already been quite successful in limiting the amount of damage a typical collision will cause by giving the subject due consideration at the model design stage.

That is a policy which Thatcham's director of research is very keen to see widely adopted. He gave me some examples of how a slightly different design at the front of a vehicle, which frequently would cost the maker little or nothing, often could save the user, through his insurance company, hundreds of pounds in repair costs.

For instance, if the battery position is close to the front of the car, the chances are that in a front-end collision it will be cracked open and acid will be spilled, causing all kinds of secondary damage.

Radiators can he saved from expensive damage too simply by mounting them a few millimetres further back.

One of the car or light commercial vehicle design features which makes Bob Ilogben shudder is an engine tie rod or front suspension strut which extends close to the extreme front of a vehicle where in a collision it will transmit large forces back to something breakable and expensive. He likes to see the front sections of chassis side rails designed so that they deform during a low-speed impact without transmitting any impact load back beyond the A post.

All car manufacturers have to submit new vehicles to statutory EEC and ECE impact tests for occupant protection. These establish whether there is a deformable zone in front of the occupants.

The statutory tests are run at 50km/h, but the standard damageability test devised by Thatcham uses an impact speed of only 15km/h. Why such a relatively low speed? Insurance company statistics show that the majority of accidents occur at about this speed, which is not surprising when you consider that most collisions are preceded by sonic heavy braking.

The same statistics also show that the vast majority of these head-on collisions involve a 40 per cent overlap — that much of the frontal area of the vehicles takes the force of the impact.

The cost of repairing such a typical accident can range from 1200 to £1,200, Bob Hogben told me. If Thatcham's research can point manufacturers towards ways of bringing their vehicle repair cost towards the lower end of that scale, then clearly it will benefit all concerned.

The Thatcham impact test procedure has now been accepted as a standard by all the major ear manufacturers and by other countries' research centres belonging to the international Research Com mittee for Automobile Repairs. Sweden's centre alone is not yet wholly convinced and has commissioned a series of tests at oblique impact angles. But it is unlikely that there will generally be accepted as more valid than the 90 deg tests already being used by Thatcham and the Allianz centre in Germany (CM, December 15, 1984), which are the only two insurance research centres with their own test rigs.

Most of Thatcham's work is concerned with cars rather than commercial vehicles, and that will certainly continue to be so, simply because of the relative sizes of the vehicle populations. But both Bob Hogben and Ken Roberts, Thatcham's manager technical services, are engineers who have worked for commercial vehicle manufacturers. They see a lot of potential in this area.

The new impact test rig is capable of pulling vehicles up to 21/2 tonnes at up to 50km/h, and several light vans have already been tested on it. But even greater potential must lie in the area of recommended repair techniques and time for cabs.

To date Thatcham has issued cab repair recommendations, including guide job times, for only two models: Ford's Cargo and Leyland's Roadrunner. In the latter case Leyland's engineers consulted Thatcham at quite an early stage in the development of the new model to ensure that they were not designing a cab that would be near impossible, or impossibly expensive to repair (CM, January 26).

This is precisely the kind of close liaison with cv manufacturers that Bob Hogben is keen to encourage. IvIIRRC representatives already have regular liaison meetings with car manufacturers, sometimes looking ahead as much as three or four years at planned models.

Another important aspect of Thatcham's work is liaising closely with repair tool and equipment manufacturers. This too is clearly an area where transport engineers could benefit from the bank of expertise that has been built up in the small Berkshire town.