Latest "Artie fa

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

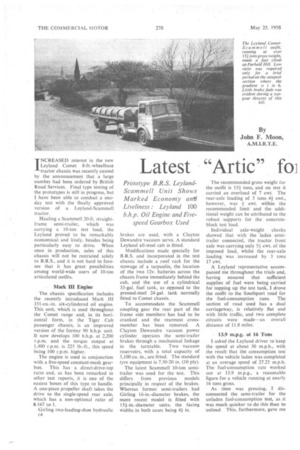

7ast Trunk Haulage INCREASED interest in the new Leyland Comet 8-ft-wheelbase tractor chassis was recently caused by the announcement that a large number had been ordered by British Road Services. Final type testing of the prototypes is still in progress, but I have been able to conduct a oneday test with the finally approved version of a Leyland-Scammell tractor.

Hauling a Scarnmell 20-ft. straightframe semi-trailer, which was carrying a 10-ton test Toad, the Leyland proved to be remarkably economical and lively, besides being particularly easy to drive. When once in production, sales of this chassis will not be restricted solely to B.R.S., and it is not hard to foresee that it has great possibilities among world-wide users of 10-ton articulated outfits.

Mark III Engine The chassis specification includes the recently introduced Mark 1-11 351-cu.-in. six-cylindered oil engine. This unit, which is used throughout the Comet range and, in its horizontal form, in the Tiger Cub passenger chassis, is an improved version of the former 90 b.h.p. unit. It now develops 100 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m. and the torque output at 1,400 r.p.m. is 225 lb.-ft., this speed being 100 r.p.m. higher.

The engine is used in conjunction with a five-speed constant-mesh gearbox. This has a direct-drive-top ratio and, as has been remarked in other test reports, it is one of the easiest boxes of this type to handle. A one-piece propeller shaft takes the drive to the single-speed rear axle, which has a non-optional ratio of 6.167 to 1.

Girling two-leading-shoe hydraulic c4

brakes are used, with a Clayton Dewandre.vacuum servo. A standard Leyland all-steel cab is fitted.

Modifications made specially for B.R.S. and incorporated in the test chassis include a roof rack for the stowage of a tarpaulin, the location of the two 12v. batteries across the chassis frame immediately behind the cab, and the use of a cylindrical 33-gal. fuel tank, as opposed to the pressed-steel 24-gal. tank normally fitted to Comet chassis.

To accommodate the Scammell coupling gear the rear part of the frame side members has had to be cranked and the rearmost crossmember has been removed. A Clayton Dewandre vacuum power cylinder operates the semi-trailer brakes through a mechanical linkage in the turntable. Two vacuum reservoirs, with a total capacity of 5,100 Cu. in., are fitted. The standard tyre equipment is 7.50-20 in. (10 ply).

The latest Scammell 10-ton semitrailer was used for the test. This differs from previous models principally in respect of the brakes. Whereas former semi-trailers had Girling 16-in.-diameter brakes, the more recent model is fitted with 15i-in.-diameter units, the facing widths in both cases being 41 in. The recommended gross weight for the outfit is 151 tons, and on test it carried an overload of 7 cwt. The rear-axle loading of 5 tons 41 cwt., however, was 4. cwt. within the recommended limit and the additional weight can be attributed to the robust supports for the . concreteblock test load.

Individual axle-weight checks showed that with the laden semitrailer connected, the tractor front axle was carrying only 51 cwt. of the imposed load, whilst the rear-axle loading was increased by 3 tons 17 cwt. • A Leyland representative accompanied me throughout the trials and, having ensured that sufficient supplies of fuel were being carried for topping up the test tank, I drove the outfit to the Southport road for the fuel-consumption runs. The section of road used has a dual carriageway, is relatively flat and with little traffic, and two complete circuits were made—an overall distance of 11.8 miles.

• 13.9 m.p.g. at 16 Tans

I asked the Leyland driver to keep the speed at about 30 m.p.h., with the result that the consumption test with the vehicle laden was completed at an average speed of 27.25 m.p.h. The fuel-consumption rate worked out at 13.9 m.p.g., a reasonable figure for a vehicle running at nearly 16 tons gross. • As time was pressing, I disconnected the semi-trailer for the unladen fuel-consumption test, as „it was much quicker to do this than to unload. This, furthermore, gave me a chance to study the performance of the solo tractor. So often, such units are almost completely unmanageable over anything approaching a rough surface because of the high degree of bounce allowed by the low unladen weight.

'Ibis was not the case with the Comet, however, and to my surprise, the tractor held the road admirably and enabled an average speed of 28.4 m.p.h. to be maintained during the test run. The average consump. tion rate was 23.1 m.p.g.

The high average speed maintained on the laden run produced the high time-load-mileage factor of 5,995, which, in a nutshell, indicates that the Comet tractor has the capacity for being worked hard, fast and economically. Much has been said for and against the safety of articulated vehicles, particularly when making emergency stops. Whilst it must be admitted that jack-knifing sometimes ,occurs. I have, so far, not experienced it while testing mediumand heavycapacity outfits. This record was to remain unbroken by the Leyland test, because emergency stops from 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. on the Southport road were conducted with a degree of safety at least equivalent to that of a conventional rigid sixwheeler.

It is desirable that the semi-trailer brakes should always be applied a little in advance of those of the prime mover, principally to avoid the risk of jack-knifing. The necessary relay valve causes a slight delay in appli

cation and, in the circumstances, the braking figures achieved during the test are particularly satisfactory, being equivalent to 0.455g. from 20 m.p.h. and 0.47g. from 30. m.p.h. Maximum pedal pressure was used and the retardation was smooth and progressive.

Further tests were carried out on the Southport road to assess acceleration times. Here, again, the Leyland outfit showed itself to be well up to scratch in getting off the mark, and the rapid changes possible with the gearbox contributed in no small way towards the good times achieved during the standing-start tests.

Gearbox Must be Used

The weight •began to tell on the engine, however, during the directdrive 10-30 m.p.h. runs.. Although the acceleration rate was reasonable, it would obviously not be desirable in service to use direct drive from as low as 10 m.p.h., even though the engine and transmission were completely vibrationless at this speed.

The hill-climb and brakefade tests were made on Parbold Hill, which is the nearest hill of any appreciable length and gradient to the Leyland factory. Parbold has a general gradient of 1 in 12 and near the summit there is a I-in-6 section.

A non-stop run was timed from the bridge at the foot of the hill, at which point the ambient temperature was

48° F. and the radiator coolant temperature was 164° F. Before making the climb, the blanking which had covered the lower half of the radiator was removed.

Six minutes were spent on the climb, and at first I thought the vehicle was going to complete it without the use of low gear. This ratio, however, proved necessary at the top of the 1-in-6 section and was engaged for approximately 30 sec. The rest of the climb was made in second and third ratios, and at no time was any smoke visible in the exhaust.

At the top of the hill a temperature rise of 10° F. in the coolant was recorded, and at this temperature the engine thermostat, if set correctly, was only partially opened.

With top gear engaged, a braked descent of the hill was made, the road speed being kept down to 20 m.p.h. By the time the unit was half-way down the hill my right leg was beginning to grow weary because of the heavy pedal pressure c6 needed, but an emergency stop on the lover slopes gave only slight signs of fade and no increased pedal travel. Similar results were obtained during a second descent, and other than the large effort required to apply the brakes, I could not find fault with the system.

Returning to the 1-in-6 section, a stop-start test was made. The tractor hand brake alone was not sufficient to hold the outfit on this gradient and it was necessary to apply the trailer brake also.

It was, however, impossible to make a smooth start, because of the impracticability of releasing two hand-brake levers simultaneously. Once all the brakes were off, the unit pulled away easily in low ratio, again without smoke. If the tractor were to be operated in hilly areas, a slightly more powerful hand-brake mechanism would be desirable.

I had plenty of opportunity to drive the outfit during the day's tests and, apart from the heavy braking, I was entirely satisfied with the way it handled. The low front-axle loading makes it extremely light to drive without inducing signs of unsteadiness at high speed, and the steering was perfectly stable at over 40 m.p.h.

I was continually being surprised at the speeds at which acute corners could be taken. Indeed, however fast I tried to take corners, I could produce no signs of instability—only slight leaning over of the tractor unit.

Generally speaking, the engine pulls well at low revolutions, and even when the gearbox is necessary it is no hardship to have to change gear. Engine noise in the cab is rather loud, but during the test I covered the bonnet with my leather driving coat, which appreciably cut down the noise.

Being only a one-day test, there was no time to carry out any maintenance checks. From previous experience of Leyland vehicles, however, I can state that routine maintenance should not cause difficulties: and a most useful tool kit is provided.