1,200 MILES ITH 19 TONS

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A.E.C. Mercury with Eagle Semitrailer Handles Well on Snow and Ice, and is Comfortable and Quiet

By John Savage, A.I.R.T.E.

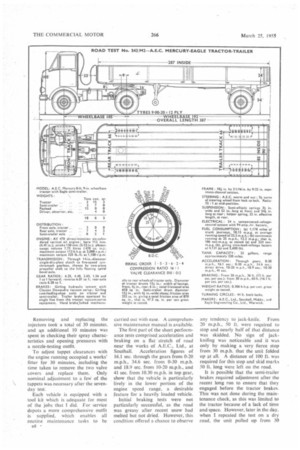

AFTER travelling 1,200 miles in the cab of an A.E.C. Mercury tractor pulling an Eagle semitrailer with a 12-ton load, I am left' with only favourable impressions of its performance, handling and

general behaviour. Cab comfort, visibility and noise insulation are also of a high standard.

The vehicle was taken over ice and packed snow and at no time did it show signs of instability. It was, of course, driven with the greatest care at all times.

Driving throughout the test at a speed not exceeding 30 m.p.h., an average running speed of 22 m.p.h. and a fuel-consumption rate of 10.15 m.p.g. were produced. The exceptional opportunity to observe the performance of this vehicle over a series of timed runs on important trunk routes in England and Wales was provided by my investigation into the effects of raising the speed limit for " heavies " to 30 m.p.h. Full details of my findings were pubfished in The Commercial Motor on March 11.

In addition•to the trunk runs, the vehicle was subjected to the usual

road performance test and it was examined in accOrdance with the maintenance programme recently introduced by The Commercial Motor. The fuel consumption on the long runs may not look impressive at first sight, but it gives a good time-load-mileage factor, considering the severity of parts of the route and the number of stops and starts made in the course of seven days' operation. A figure of 12.2 m.p.g. was later obtained over a continuous 10mile run at 25 m.p.h.

The AV 470 six-cylindered directinjection oil engine of 7i-litre capacity powers the Mercury. It has the A.E.C. open toroidal combustion chamber, renewable wet cylinder liners and a seven-bearing crankshaft. Fuel-injection equipment on the vertical model (which is used in the Mercury) is made by C.A.V., Ltd., and Simms equipment is employed on the horizontal version of this engine.

My tests included a journey over the Pennines and at no time did the engine falter. The torque curve seems to be ideally matched to the gear ratios and on gradients of about 1 in 20 the engine pulled happily in third gear. The five-speed inertia-lock synchromesh gearbox is mounted as a unit with the engine. Rubber-sandwich mounting blocks are used at the front and conical rubber units at the rear.

Under all conditions of operation the cab is noticeably free from engine vibration. All but the first and reverse gears are synchromesh. and the simplicity of gear changing is one of the outstanding points of the vehicle.

Another, feature that deserves praise is the riding quality of the tractor. Shock absorbers are fitted to the front axle on export chassis only, yet on the long runs there were only a few occasions when! noticed their absence from the test vehicle.

Girling two-leading-shoe brakes are fitted to the tractor and semitrailer, and all brakes are operated by the Girling hydraulic system and Clayton Dewandre vacuum servo of the tractor. After descending a long hill in the Pennines, with the brakes fully engaged, they smoked a little, but there was no evidence of fade.

The semi-trailer had a drop-sided body with a D-shaped front. Its chassis was constructed of pressed ;hannel sections and outriggers, and be floor was made of wood. crewed-down jockey wheels were ;lightly inclined from the vertical to give the greatest stability when the railer was disconnected.

Between the trunk journeys and he short performance tests, the trac.or was made available for a mainenance check. Only 24 pints of oil Nere added to the engine sump after 1,200 miles with a full load and only t drop of distilled water was needed o cover each of the battery plates. To check all fluid levels and top-up where necessary took me 30 minutes. The battery under the driver's seat can be topped-up without removing the seat if a rubber tube is attached to the filler bottle, but the passenger seat must be taken out to reach the battery on the near side.

The radiator grille has to be removed to check the level of grease in the steering box. The dynamo fan belt can be adjusted for tension at the same time.

Removal and replacement of the grille is a simple operation if you do not dislodge the rubber fillet, as I did. This is one of those small things that try the patience of a driver or fitter, and a fillet that stays in place would be an advantage. '

Under the guidance of a works' fitter, I located all the grease nipples and, using a power gun, I greased the tractor, with its turntable unit, in about 20 minutes. Bleeding and adjusting the brakes took 24 minutes. No adjustment was necessary, although the brakes had frequently been used to hold the vehicle to my self imposed speed limit of 30 m.p.h. on the 1,200-mile run.

I went through the procedure of taking up the adjusters until the brakes rubbed, and then when I slackened them off they were back in their original position. This spoke well for the resistance of the brake facings to wear.

Simply removing the single cover in the cab reveals the whole top portion of the engine, and it was possible to take out the injectors, check the tappet clearances, and renew the fuel-filter element without detaching the two side panels. Removing and replacing the injectors took a total of 30 minutes, and an additional 10 minutes was spent in checking their spray characteristics and opening pressures with a nozzle-testing outfit.

To adjust tappet clearances with the engine running occupied a works' fitter for 30 minutes, including the time taken to remove the two valve covers and replace them. Only nominal adjustment to a few of the tappets was-necessary after the sevenday test.

Each vehicle is equipped with a tool kit which is adequate for most of the jobs that I did. For service depots a more comprehensive outfit is supplied, which enables all routine maintenance tasks to be a8 • carried out with ease. A comprehensive maintenance manual is available.

The first part of the short performance tests comprised acceleration and braking on a flat stretch of road near the works of A.E.C., Ltd., at Southall. Acceleration figures of 16.1 sec. through the gears from 0-20 m.p.h., 34.6 sec. from 0-30 m.p.h. and 18.9 sec. from 10-20 m.p.h.. and 41 sec. from 10.30 m.p.h. in top gear, show that the vehicle is particularly lively in the lower portion of the engine speed range. a desirable feature for a heavily loaded vehicle.

Initial braking tests were not particularly successful, as the road was greasy after recent snow had melted but not dried. However, this condition offered a chance to observe any tendency to jack-knife. From 20 m.p.h., 50 ft. were required to stop and nearly half of that distance was skidded. No sign of jackknifing was noticeable and it was only by making a very fierce stop from 30 m.p.h. that the unit folded up at all. A distance of 100 ft. was required for this stop and skid marks 50 ft. long were left on the road.

It is possible that the semi-trailer brakes required adjustment after the recent long run to ensure that they engaged before the tractor brakes. This was not done during the maintenance check, as this was limited to the tractor because of a lack of time and space. However, later in the day. when I repeated the test on a dry road, the unit pulled up from 30 1.p.h. in 60 ft. without the slightest :ndency to jack-knife. Even when escending ice-covered slopes on the mg-distance test, the semi-trailer lowed no sign of deviating from 3urse, although, naturally, the driver ave it little opportunity to do so.

Manceuvring at Speed I was anxious to see how the ehicle handled at its maximum peed of 40 m.p.h., so I drove to tickmansworth with my foot hard own. I was impressed, as I had .een when I previously drove the chicle at 30 m.p.h., with the ease iith which this unit could be laneeuvred at speed and when rawling through traffic.

Two climbs up 1-in-8 hills near tickmansworth produced a temperaure rise of 12° F. in the first case nd 5° F. in the second. The econd was a 21-minute pull for vhich second gear was used for most )1' the time. With an ambient tern)erature of 40' F., the rise of 17° F. vas not sufficient to take the coolant emperature above the figure of 75° F. at which the thermostat yens.

At the steepest part of Ducks Hill, Niorthwood, where the gradient is ilmost 1 in 6 for a short distance, I ;topped the vehicle and held it on he hand brake. Closer adjustment the brake would have been deskible, but it held safely on the last iotch ; I then punished the transmission ;ystem severely by trying a start in ;econd gear. After I had stalled the engine twice, the vehicle ran back down the hill on the third attempt, while the fully engaged clutch slipped

furiously. Apart from the smell of burnt clutch facing, all was well, and with the clutch still overheated we made a perfect start in the creeper gear. On a 1 in 9 section of the hill, a successful start was accomplished in second gear.

This test brought to light one small shortcoming of the gearbox. When changing from first gear, the lever tends to spring into the fourth-gear position. Familiarity would enable a driver to master this operation. but as the first gear is so rarely used, I think a weaker spring should be fitted to the selector mechanism.

As a 1,200-mile run is not the usual basis for The Commercial Motor fuel-consumption tests, I completed the day's trials by measuring the fuel consumed in a test tank during a 10-mile run from Ruislip to London Airport. The journey took 26

minutes, two of which were spent at traffic lights. The indirect gears were used to get away from the two traffic-light stops and on three other occasions.

12.2 m.p.g. at 25 m.p.h.

The quantity of fuel used was 3,735 c.c., which is equal to 12.2 m.p.g., at an average speed of 25 m.p.h. For a vehicle with a gross weight of 18 tons 6 cwt., this is a reasonable figure and gives a highly satisfactory time-load-mileage factor of 5,600.

Now that the 25-mile restriction on free-enterprise hauliers has been 'lifted, interest in the performance of heavily loaded semi-trailer outfits has increased. My tests show that the Mercury is a reliable and easily serviced vehicle. The simple coupling arrangement of the semi-trailer permits a quick turn-round at terminals and promotes efficiency and economy in operation, together with adaptability to a number of different carrier units.

In the event of an increase in the speed limit for goods vehicles weighing over three tons unladen, higher average running speeds would be possible. Running time, therefore, becomes more valuable, and time wasted at terminals will represent a greater loss.

An increased average speed might not alWays be beneficial . as the problems connected with loading and unloading can nullify the advantages of a shorter journey time, " Artics " can be used to great advantage in keeping turn-round times to a minimum and thereby make a higher average speed worthwhile.