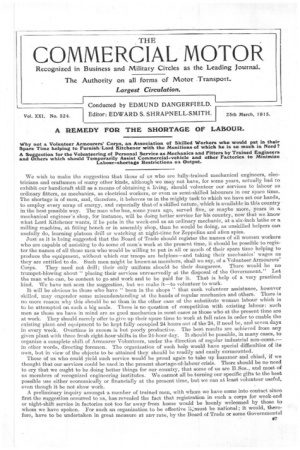

A REMEDY FOR THE SHORTAGE OF LABOUR.

Page 1

Page 2

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Why not a Volunteer Armourers' Corps, an Association of Skilled Workers who would put in their Spare Time helping to Furnish Lord Kitchener with the Munitions of which he is so much in Need ?

A Suggestion for the Volunteering of Personal Service as Mechanics and Fitters by Trained Engineers and Others which should Temporarily Assist Commercial-vehicle and other Factories to Minimize Labour-shortage Restrictions on Output.

We wish to make the suggestion that those of us who are fully-trained mechanical engineers, electricians and craftsmen of many other kinds, although we may not have, for some years, actually had. to exhibit our handicraft skill as a means of obtaining a living, should volunteer our services to labour as ordinary fitters, as mechanics, as electrical workers, or even as semi-skilled labourers hi our spare time. The shortage is of men, and, therefore, it behoves us in the mighty task to which we have set our hands, to employ every scrap of energy, and especially that of a skilled nature, which is available in this country in the best possible way. The man who has, some years ago, served five, or maybe more, years in a mechanical engineer's shop, for instance, will be doing better service for his country, now that. we know what Lord Kitchener wants, if he puts in the week-end as an ordinary mechanic, at a six-inch lathe or a milling machine, at fitting bench or in assembly shop, than he would be doing, as unskilled helpers can usefully do, learning platoon drill or watching at night-time for Zeppelins and alien spies. Just as it is being suggested that the Board of Trade should register the names of all woman workers who are capable of assisting to do some of men's work at the present time, it should be possible to register the names of all those men who would be willing to put in all or much of their spare time helping to produce the equipment, without which our troops are helpless—and taking their mechanics' wages as they are entitled to do. Such men might be known as members, shall we say, of a Volunteer Arrnourers' Corps. They need not drill; their only uniform should be their dungarees. There would be no trumpet-blowing about" placing their services unreservedly at the disposal of the Government." Let the man who can, be content to go and work and to be paid for it. That is help of a very practical kind. We have not seen the suggestion, but we make it—to volunteer to work.

It will be obvious to those who have " been in the shops " that such volunteer assistance, however skilled, may engender some misunderstanding at the hands of regular mechanics and others. There is no more reason why this should be so than in the other case of the substitute woman labour which is to be attempted on such a big scale. There is no question of competition with existing labour: such men as those we have in mind are as good mechanics in most cases as those who at the present time are at work. They should merely offer to give up their spare time to work at full rates in order to enable the existing plant and equipment to be kept fully occupied 24 hours out of the 24, if need be, and seven days in every week. Overtime in excess is but poorly productive. The best results are achieved from any given plant with three fresh eight-hour shifts in the 24-hour day. It should be possible, in many cases, to organize a complete shift of Armourer Volunteers, under the direction of regular industrial non-corns.— in other words, directing foremen. The organization of such help would have special difficulties of its own, but in view of the objects to be attained they should be readily and easily surmounted. Those of us who could yield such service would be proud again to take up hammer and chisel, if we thought that our services could be used in the present shortage-of-labour crisis. There should be no need to cry that we ought to be doing better things for our country, that some of us are B.Scs., and most of us members of recognized engineering institutes. We cannot all be turning our specific gifts to the best possible use either economically or financially at the present time, but we can at least volunteer useful, even though it be not show work.

A preliminary inquiry amongst a number of trained men, with whom we have come into contact since first the suggestion occurred to us, has revealed the fact that registration in such a corps for week-end or night-shift service in factories not too far away from home would be keenly welcomed by those to whom we have spoken. For such an organization to be effective 14'must be national; it would, therefore, have to be undertaken in great measure at any rate, by the Board of Trade or some Governmental organization. Purely as a preliminary and in order to provide a nucleus, to be handed over if need be, we have been happy to open a register of names of those to whom this idea of a National Volunteer Armourers' Corps appeals. We shall be happy to have criticisms and suggestions from those of our readers who consider the suggestion worth further consideration.

A FEW OF THE REASONS WHICH HAVE PROMPTED OUR ACTION.

We all of us now know what, perhaps, it would have been better we had known earlier. We have been told by Lord Kitchener that " the supply of war material at the present time, and for the next two or three months, is causing very serious anxiety? It is absolutely essential that the arrears in the deliveries of our munitions of war should be wiped off."

This candid statement of fact, coming as it does so promptly on top of the Government's announcement of its intention so to amend the Defence of the Realm Act as to enable it to assume still more farreaching powers in regard to factory organization and control, renders it easy for the least intelligent of us to understand that this war depends as much upon our ability to turn out manufacturing equipment to the best possible advantage as it does to place two, three or four million men in the field. Help is wanted as much at the lathe as in the trenches.

Following the recent meeting of the Association of the Chambers of Commerce, in London, the President, Sir Algernon Firth, stated his opinion that it was " not necessary for the Government to take over the workshops in order to secure a maximum of production," whilst from the labour side of the question comes the definite expression of opinion that it is useless to expect men to work at greater pressure than that as a rule existing at the present time. In other words both masters and men are cognizant of the fact that there is a, very distinct limit to the human possibilities of individual labour output. This is a point of view to which we have already, but a few weeks ago, drawn attention in connection with the recent Liverpool dock strike. The new Government measures have, thus, as the result of their first consideration and discussion, revealed the fact that the country's most pressing danger is shortage of labour, not shortage of material or facilities.

There is no need at the moment further to enforce the point with regard to the Government's failure to appreciate the necessity of forbidding the recruiting of skilled workers who shortly would be more badly wanted in the shops than they could ever be in the trenches. We need not now do any more than record, as a contributory cause of some importance, the reprehensible and almost criminal " whitefeather " folly of a few months ago, when crowds of immature girls were allowed insolently to plague those men whom they met in the streets who did not happen to be in uniform—one of many instances of misapplied effort, but one which, as it happened, was successful in recruiting thousands of men, particularly in districts where skilled labour was already at a premium. These and other mistakes have been made, with the result that we are now faced with a.shortage, and a very serious one too, of skilled and semi-skilled labour, and not leastin commercial-vehicle factories and pleasure-car works at present producing munitions of war. Our authoritative contemporary " Engineering," amongst others, writes editorially, " The real crux is not the unreadiness of the employers to undertake war contracts . . . but to get men to execute the work." There are those who would tell us that semi-skilled labour is the more difficult to obtain at the moment, and that there are plenty of people to man, day and night, all the machine tools which can be used in the production of munitions of war of all kinds, that classification including, of course, the commercial vehicle as much as it does the gun carriage. The great need, they will tell you, is for the semiskilled helper in foundry and forge—that the restriction of output is largely due to the difficulty of obtaining their supplies. There are others who complain of a serious shortage of skilled help. There is very real difficulty in dealing with the work-shy workman who finds his country's crisis an easily-attained opportunity to earn more money than he deserves, in as few hours as possible, without harm to his skin.

As we write, particulars of one of the immediate steps to be taken to overcome the shortage-of-labour difficulty, whatever be its specific nature, have been published by the Board of Trade. Great efforts are to be made to employ more woman labour, not only in munition factories, but in other undertakings where they will be able to do substituted service for men, who can then be spared for the Front—a solution to our problem of an indirect nature only, unless such new recruits can again be substituted for mechanics at present at the Front. There is some doubt, in industrial circles, that more extended use of female labour can be made in trades where it already exists. Their increased occupation in toymaking and allied trades, as suggested, will surely release but few men. The more extended use of woman's manual help in factories may nevertheless prove a partial solution of the shortage-of-labour problem. Other relief, to the detriment of non-warlike productions, may be secured by the concentration of skilled men in factories only engaged on W.D. contracts.

We, as a nation, have to face the problem of providing more assistance of one sort and another in and about our factories by hook, by crook, or by any manner of means. There has.beenno lack of volunteering tvhether it be to police the streets on lonely night watches, or to guard reservoirs and gasometers, or whether it be during week-ends and other off times to embark on a course of preliminary military training, which it is hoped will ultimately prove of benefit to the country. Good work, of a precautionary if not immediately-productive nature, is being done by volunteer helpers in these and other spheres, yet it is a fact that neither of the two great movements, to which those who are not in the Forces have so readily responded, yields sufficiently immediate results to warrant its being considered more important than would a similar movement were it directed to help Lord Kitchener in the production of munitions.