Ssu-Kung-L-Pan

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By Jack Jones of the Friends' Service Unit (Chino)

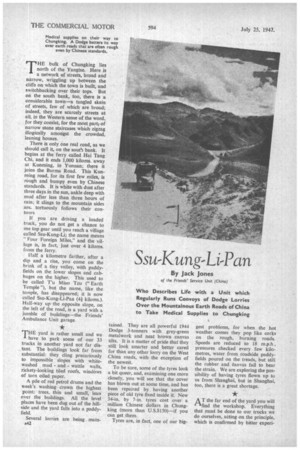

Who Describes Life with a Unit which Regularly Runs Convoys of Dodge Lorries Over the Mountainous Earth Roads of China to Take Medical Supplies to Chungking

THE bulk of Chungking lies north of the Yangtse. Here is a network of streets, broad and narrow, wriggling up between the cliffs on which the town is built, and switchbacking over their tops. But on the south bank, too, there is a considerable town—a tangled skein of streets, few of which are broad; indeed, they are scarcely streets at all, in the Western sense of the word, for they consist, for the most part; of narrow stone staircases which zigzag illogically amongst the crowded, leaning houses.

There is only one real road, as we should call it, on the south bank. It begins at the 'ferry called Hai Tang Chi, and it ends 1,000 kiloms. away at Kunming, in Yunnan; there it joins the Burma Road. This Kunming road, for its first few miles, is rough and bumpy even by Chinese standards. It is white with dust after three days in the sun, ankle deep with mud after less than three hours of rain; it clings to the mountain sides arm tortuously follows their contours If you are driving a loaded truck, you do not get a chance to use top gear until you reach a village called Ssu-Kung-Li; the name means " Four Foreign Miles," and the village is, in fact, just over 4 kiloms. from the ferry.

Half a kilometre farther, after a dip and a rise, you come on the brink of a tiny valley, with paddyfields on the lower slopes and cabbages on the higher. This used to be called T'u Miao Tzu C' Earth Temple "), but the name, like the temple, has disappeared; it is now called Ssu-Kung-Li-Pan (4?; kiloms.). Half-way up the opposite slope, on the left of the road, is a yard with a jumble of buildings—the Friends' Ambulance Unit garage.

THE yard is rather small and we have to park some of our 33 trucks in another yard not far distant. The buildings look far from substantial: they cling precariously to impossible slopes with whitewashed mud and wattle walls, rickety-looking tiled roofs, windows of torn oiled paper.

A pile of red petrol drums and the week's washing crown the highest point: trees, thin and small, lean over the buildings. All the level places have been dug out of the hillside and the yard falls into a paddyfield.

Several lorries are being mains42 tamed. They are all powerful 1944 Dodge 3-tonners with grey-green metalwork and neat brown canvas tilts. It is a matter of pride that they still look smarter and better cared for than any other lorry on the West China roads, with the exception of the newest.

To be sure, some of the tyres look a bit queer, and, examining one more closely, you will see that the cover has blown out at some time, and has been repaired by having another piece of old tyre fixed inside it. New 34-in. by 7-in. tyres cost over a million Chinese dollars in Chungking (more than U.S.$150)—if you can get them.

Tyres are, in fact, one of our big

gest problems, for when the hot weather comes they pop like corks on the rough, burning roads. Speeds are reduced to 18 m.p.h , pressures checked every few kilometres, water from roadside paddyfields poured on the treads, but still the rubber and anvas fail to bear the strain. We are exploring the possibility of having tyres flown up to us from Shanghai, but in Shanghai, too, there is a great shortage.

A T the far end of the yard you will "find the workshop. Everything that must be done to our trucks we do ourselves, acting on the principle, which is confirmed by bitter experi ence in China, that if you want a job to be done well, you had better do it yourself, .•We haveour own boring bars, for no engine can withstand more than about 9,000 miles of these gruelling, mountainous roads without wearing itself out; and every one of .our 50 odd engines has now been rebored at least once. We have lathes and a generator to drive them, and a fully equipped test bench on which the rebored engines are run in. The reboring is done by a foreigner—an amateur, as we all are—but the chief mechanic is Chinese., There are 50 employees in all, including.. blacksmiths, tinsmiths, carpenters, turner, electricians; appren• tice-mechanicS, and road.. boys. There is `plenty.of work for them all too, for :WheneVer a vehicle comes in it will, have some " mao pin," great or small.

Home Made Here ii The turner making a new, jet, becanse jets of the size we want . are unobtainable in Chungking. There is the welder mending a chassis, cracked on a bumpy stretch of road in the north.The tinSmiths are busy repairing radiators and metalwork.

Two of the Carpenters are sawing industricitisly at a baulk of timber, while the third, old Tseng Yu Shan, is repairing a bed-board. (The drivers sleep on their trucks when on the road, spreading their " p'u kais " on a board which fits on the cab roof, pulling the canvas over their heads for ptotection from rain. Part of the yard is covered in, and under this shelter a dozen mechanics and boys are busy overhauling gearboxes, brake systems (another constant source of trouble), axles, water pumps and the like. Everybody looks very busy, but the garage staff has learnt not to judge by appearances in this matter: mechanics are the same all the world over, and have a genius for looking busy when they are not.

3UDDENLY a gong sounds (it is an old tyre rim, struck with a small bar of iron), and with whoops of joy the employees rush off to eat. Many of them, who have wives and families, live in the villages around; but rather more than 20, men and boys, live id our own employees' hostel.

They sleep in dormitories above the workshops, and eat their three meals a day in a small, shed clinging to the hill above. They receive the same wages as the men who live outside, but a certain part (which varies from month to month) is deducted for food.

We members have a hostel of our own. It is by no means a commodious building. It is made in the usual style—a frame of slender logs, filled in with walls of mud and wattle; the tile roof often leaks,•and dogs and rats constantly break through the walls; but we have a Western-style fireplace in the livingroom, and a thatched verandah to foil the sun and the rain. There are three rooms in all, two . -filled with bunks and all our belongings. The third is the room in which we eat, read, write, talk, play games, and spend most of our spare time.

There is always great excitement when a convoy returns. We members and our seven dogs rush out of our hostel, whilst the employees pour out of theirs. There is a great slamming of cab doors and revving up of engines before they are finally switched off. ' unshaven, dirty, tousle-headed, wearing strange mixtures of Chinese and Western civilian and military garb, the drivers, foreign and Chinese, climb stiffly out of the cabs.

There is much shaking of hands, slapping of backs, and punching of ribs. The convoy leader is besieged with questioners.

A Tale of Woe Maybe it was a trip full of trouble; water in the petrol, three or four flats or blow-outs, leaking radiators, slippery roads, trouble with the Army, or a bad dose of stomach trouble. Sometimes it is worse: a truck overturned or an engine seized, by no means infrequent occurrences.

Whatever his story, the convoy leader is sure of a warm welcome. It is a great moment. Another hospital has been provided with its medical supplies.

For a fortnight, perhaps, the convoy leader will be overhauling his trucks and collecting 'his next cargo. Then he will be off into the blue again for another month.