Is Ancillary

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Operation Cheaper ?

Description of a Favoured Method by Which Many C-licensees Compare Their Costs Against the Alternative Use of Hauliers' Services : Care Needed in Interpretation

FOR a haulier, the iflair' object of keeping cost records is to be able to calculate rates, or, if charges have to be quoted on a less methodical basis, to check that earnings are sufficient to yield a profit. •An ancillary user, however, is perhaps chiefly interested in his expenses because he wishes to know the kind of work for which it is better to use his own vehicles rather than employ a haulier, assuming that there are no special conditions under which a general contractor could not provide the required service.

Other good reasons for recording and analysing costs in detail include the comparison of performance of different types of vehicle and the economies effected by revisions of methods of operation, but these apply equally to hauliers and C-licensees. Many Ancillary users (mostly, I have noticed, those whose _fleets are managed by men with experience in professional haulage) check their costs against the sums they would otherwise have paid for work performed had it been done by a haulier at standard rates, that is reasonable charges, not rates which have beep blindly cut for some reason and bearing no relation to actual expenditure.

For example, if 5 tons of goods have to be moved for a journey. of 100 miles, a haulier might quote £7 10s. The C-licensee, by reference to his costings, could quickly see whether the expense involved in using one of his own vehicles is higher or lower than this amount, taking empty running into account. If his costs are less than the price he might pay a haulier, he can be satisfied that his fleet is saving money, but if the reverse applies either some justification must he found or there is good reason to employ a haulier.

A system of this kind is not difficult to work. The pre requisite, of course, is a knowledge of standard haulage rates for the class of traffic concerned for various distances. In most cases, where ancillary operators are also users of general haulage facilities and to whom this method of comparison is of greatest interest, this information will be readily available. The next step is to price each job done by the fleet according to those rates.

What may be called a profit-and-loss account is made out for each vehicle, and the delivery of each load is. noted upon it. Charges that a haulier would have made are put down against each job and totalled at the end of week, or any other period as may be desired. To compare the cost of performing the work under C licence, it is unnecessary, and indeed misleading, to work out an individual item of expense for each job to compare with the hypothetical haulage rate.

When the "haulier's charges" are added, the mileage covered by the vehicle during the week is reckoned. The operator would, of course, know the running cost per mile and the standing charges per week for the vehicle concerned, and could thus compute the expense of operating the vehicle in that period. This sum is to be compared with the total of estimated haulage charges.

Unwise Course

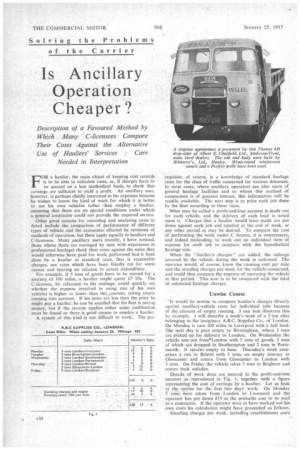

-It would be unwise to compare haulier's charges directly against ancillary-vehicle costs for individual jobs because of the element of empty running. I can best illustrate this by example. I will describe a week's work of a 5-ton oiler belonging to the imaginary A.B.C. Supplies Co., of London. On Monday it runs 200 miles to Liverpool with a full load. The next day it goes empty to Birmingham, where 3 tons are picked up for delivery to London. On Wednesday the vehicle sets out from•London with 5 tons of goods, 3 tons of which are dropped in Southampton and 2 tons in Portsmouth. It retufns empty to base. Thursday's work comprises a run to Bristol with 5 tons, an empty journey to Gloucester and return from Gloucester to London with 3 tons. On Friday the vehicle takes 5 tons to Brighton and comes back unladen.

Details of work done are entered in the profit-and-loss account .ás reproduced in Fig. 1, together with a figure representing the cost of carriage by a haulier. Let us look at the . entries for the first two days' work. On Monday 5 tons were taken from London to Liverpool and the operator has put down f15 as the probable cost to be paid to a contractor. If the operator were to have wailed out his own costs his calculation might have proceeded as follows.

Standing charges per week, including establishment costs and wages, amount to £14 10s., so that per day of a five-day week the sum is 12 18s. Running costs come to 10d. a mile and for a journey from London to Liverpool would total /8 6s. 8d. The gross cost for the, trip is therefore £11 4s. 8d. The operator compares this with the £15 he might shave paid a haulier and imagines he has saved 13 I5s. 4d.

Reckoning how much the next day's work would have cost him, he puts down £1 9s. for standing charges, on the basis that Birminghain-London is half a day's work, and adds to this 110 miles at 10d. a mile. £4 I Is. 8d., making a total of £6 Os. 8d.

Knowing that had a haulier carried this load the charge would have been only £5, the operator notes that his own expenses were greater by £1 Os. 8d., but is nevertheless satisfied that on the round journey there has been a saving because the Monday's outward run savell £3 15s. 4d:, making a net economy of £2 14s. 8d.

Reasoning Gone Astray

It should be obvious where his reasoning has gone astray. He has forgotten to include in his calculations the time and mileage involved in running from Liverpool to Birmingham, which was, oecourse, empty. It can therefore be seen that if this system is to be correctly interpreted, the unsafe method is to work out a cost for each job to compare with the haulage charge. The dead-mileage element does not come to light if this is done. In the week this 5-tonner covers 825 miles but for only about 730 miles is it carrying goods. For an ancillary user this can be considered efficient. The relative economy of ancillary operation and the use of general services largely turns upon the laden-mileage factor that the operator can achieve. Operating costs for the week are £14 10s. for standing charges plus 825 miles at lOd a mile, making £48 17s. 6d. in all.

Against each job performed by the vehicle is a haulier's estimated charge and these total £49. On the basis of cost alone, the operator therefore reckons to have saved 2s. 6d. Let us say that he has broken even, a position he has achieved by being able to load his vehicle for a high proportion of its week's mileage and which he could have improved upon by loading to capacity on those runs when only part-loads were carried.

The important point is that this system fonts a valuable tool of management to the chief of a ,C-licence fleet. This article has been written with present difficulties in mind, but on the premiss that normal conditions prevail. I would suggest that while road transport business is slack at the moment, operators should overhaul their costing systems and the manner in which they apply the figures that vehicles „return.

A costing system is a mere chronicle of accounts if no use is' made of it, such as by the method described here. There is no doubt that when fuel is again freely available. road transport operators will have ,to struggle through a period of general economic difficulty, and any means for detecting inefficiency in the conduct of a business will be of great value. S.T.R.