What the strike means to hauliers

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Coal-lorry convoys can spell survival. 'The prospect of blacking after the dispute is irrelevant if you cannot otherwise survive that long': Jack Semple reports from South Wales

MY FIRST sight of the reality of the miners' strike in South Wales was from above the M4 at junction 27, the turn-off for Ebbw Vale. I counted more than 130 tipper lorries in close formation in the centre lane of the motorway, all with tarpaulins over their load, and many with ugly metal grilles across their windscreens.

Police cars and motorcycles escorted them, and traffic was being stopped on the slip road eastbound from joining the motorway. This extraordinary sight of so many lorries in convoy carrying raw materials the 50 miles from Port Talbot to Llanwern steel works is seen several times every day.

These convoys dominate that stretch of the M4 which now carves its way through the heart of industrial Wales. This scene is the most visible reminder of the tragic, pervasive strike which is splitting the country, but particularly South Wales, in two.

To local tipper hauliers it is also a constant reminder that the strike is bringing salvation for some and despair for others. Some say it is the costliest dispute since the general strike in 1926.

But while immediate survival has been the problem for many hauliers, the question at the back of everyone's minds is: What happens after the strike is settled? The threat of widespread blacking is strong, the likelihood uncertain.

What is certain, is that the effect of the strike on tipper hauliers in the close, almost claustrophobic atmosphere in South Wales is as severe as anywhere in the country.

Not far from Ebbw Vale lies the town of Bargoed, and near there the village of Den. Towns in Welsh valleys tend to run into each other. At the far end of Den, Alan Price has built two houses for himself, his wife and sons, and has a fleet of 28 tippers. These vehicles are very well known in the area, all in distinctive blue livery, and all with a Michelin man above the cab. They mostly work for the National Coal Board, and most of them have hardly turned a wheel for more than six months. Fourteen drivers have been laid off, and more lay-offs are likely.

Mr Price comes from a mining family, and many of his drivers are former miners. At first he had sympathy for the miners' strike, but that has long since gone because of the miners' tactics during the dispute. Although Mr Price's lorries have clearly not been carrying much traffic anywhere — he has three new Ford Cargo six-wheelers, which joined the fleet in February and have still to carry their first loads — the National Union of Mineworkers has stopped him from carrying what traffic is available.

Concessionary coal loads agreed with the NUM were offered to Mr Price seven weeks ago by the NCB. The NUM had inspected the tailgates on Mr Price's lorries to verify that they were rusty and therefore had not been used. Two days after he started doing the work, a picket accused the firm of breaking a picket line on one occasion at Bagworth in March, and Mr Price's lorries were blacked.

Mr Price denied that he had sent a lorry to the site, never mind crossed a picket line. The picket making the accusation was unable to identify the driver or the registration number, but was certain that it was one of Mr Price's lorries.

In the end, NUM boss Terry Thomas, based at the area headquarters in Ponypridd, told Mr Price that the members were paying his wages and there was nothing he could do.

The Transport and General Workers' Union was no help either, Mr Price said.

Mr Price's firm is not particularly popular with some NUM members, he told me. "One of our lorries on pit work can do three loads in a day in the time it takes an NCB lorry to do two. They didn't believe we were running legally and our records were checked by the NCB's head of transport for East Glamorgan."

Mr Price's situation is not as bad as it might have been, because he has a very cautious approach to committing money. He pays off two thirds of the cost of a new lorry in the first year, and the rest over the second 12 months. But he has already sold six lorries which he would otherwise have kept.

He has the chance of new traffic, loads of aggregates to the London area, but there will be 'little profit' in the work. Rates are very low, and his air-cooled Deutz-powered tippers, ideal for the punishing work in the Welsh valleys (anything with a radiator will boil its head off), will prove thirsty on the long motorway haul.

I asked Mr Price if he had considered joining the Llanwern convoys. He told me that if he thought the hauliers on the convoys at present would be successful in getting NCB work after the strike, he would go on the convoys tomorrow, but instead he has turned work away. "I have been brought up too near the woods to be frightened by owls," he added.

Alan Price's predicament is typical of that of most NCB contractors. If you see tipper lorries standing idle, the chances are they work for the NCB.

Cross Hands, four miles west of the end of the M4, is a small town built around a single cross-roads. The main road, the A48, carried traffic on to Carmarthen, Pembroke and Milford Haven. Turn left to Tumble — a select and expensive suburb of Swansea — turn right, and you are on the edge of another coalfield. Drive on this last road any evening and you will find a row of about two dozen smart tipper lorries, belonging to Williams Bros, part of British Fuel Group, parked on hard standing in front of a coal yard. There is no security to speak of, except that they are open to view from the road.

Return the following day, and you will find they are still there. Their drivers have been laid off and they have hardly turned a wheel in months.

At nearby Mordav Coal, Road Haulage Association District chairman Jack Davies is in a similar position. He has laid off 33 men, and those who are still working spend much of the time painting the lorries. There is no coal to carry.

"I may say that the strike is the lesser of the two evils," he told me. For months before the all-out strike, the miners' overtime ban meant that coal tippers in the area could work only for four hours a day, and then less efficiently than normal. "You can get bankrupt in bed and you can get bankrupt running a lorry on the road."

Mr Davies still has some lorries running, bringing agricultural supplies into the area for long-standing customers. But with little traffic going out, there is little profit there. Rates have held up reasonably on existing work, but on new traffic they are cripplingly low, he said.

Mordav's revenue since last November is down by around E1/2m owing to the miners' strike. Money set aside to replace lorries — usually three or four are bought each year — has instead been put into keeping the business going. Mr Davies has been asked to put lorries on the steel convoys, and could easily put 15 on, but has so far refused. "We question ourselves very often whether we are right or wrong," said Mr Davies. "I don't see how they can black people who are saying they are exercising their right to work — the same as the miners are saying."

If the strike goes on for another three months, there will be wholesale haulage closures, Mr Davies predicted. "And you won't get as many people going into haulage as you have in the past."

There will have to be a new appraisal of all aspects of tipper haulage after the strike. Drivers will be less willing to strike than in the past, and relations between employers and the Transport and General Workers' Union will improve — and haulage rates will have to go up.

Elwyn Morgan, the Bridgendbased head of road transport for the NCB in South Wales, told me that the extent to which the NUM would black lorries is "the $64,000 question".

"I am not aware that any of our regular hauliers have been involved in work which would lead to blacking by the NUM after the strike," Mr Morgan said. As far as he knew individual hauliers decided to stand up their vehicles on their own volition.

There has been no discussion between these hauliers and the NCB, he said.

But these hauliers will certainly not receive preferential treatment from the NCB. "At the end of the strike we will revert back to normal working." This means that normal commercial rules will apply, with the cheapest tender being picked first for work. Mr Morgan said he could see no purpose in reviewing rates, or in changing the system by which hauliers are selected.

The Board's use of haulage contractors has fallen by around 90 per cent. However, some NCB and contractors' lorries have been working, for example, on concessionary coal. And the NCB's own lorries have been carrying coal from opencast sites to distribution depots, where bagging crews have car ted household coal, Mr Morgan said.

The main focus of the strike in South Wales has been on Llanwern steel works, however, where miners, desperate to increase their pressure on the Government, have tried to blockade coal and iron ore supplies to the steel works. They gained the support of the National Union of Railwaymen, which refused to carry the traffic, so it was switched to road.

A massive 75,000 tonnes a week of material which would normally come in by rail has been transfered to road. Hauliers carrying the traffic have given the steel complex what BSC itself describes as "a lifeline".

The man who has been organising the convoys is Martin HazeII, who runs a fleet of lorries based near the works. He has been using his own 17 tippers on the convoys and subcontracting the rest, using around 200 additional lorries. He told me that as BSC is his major customer, he could not refuse the work. The convoys have put some hauliers back on their feet who would otherwise have gone to the wall. Dozens of miners have phoned him asking: "You can organise the hauliers, can you get us back to work?"

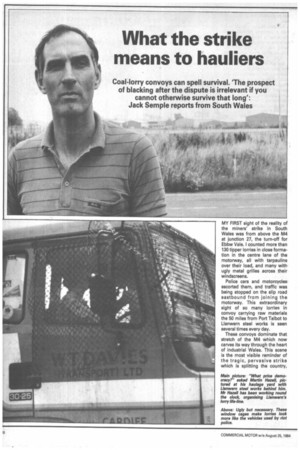

Mr Hazell believes the blacking threats will recede after the strike, and he intends to continue in haulage. But if the firm is put out of work because of blacking after the strike, Mr HazeII can fall back on substan Left: Elwyn Morgan has no answer as yet to the $64,000 question.

Far left: RHA district chairman Jack Davies of Mordav Coal predicts a huge improvement in relations between employers and the TGWU "Humour will overtake acrimony."

tial plant contracts within Llanwern steel works.

Mr Hazell said his drivers' attitude to the strike has hardened following violence against them and the company. Cab windscreens have been smashed and the firm's offices were gutted by fire.

Claims by the NUM that tippers in the convoy are running illegally are untrue, he said, and he showed me reports from police giving details of spotchecks on the lorries in the convoys within Port Talbot works, including their weights. None of the tippers was running overloaded.

Other hauliers confirmed that the daily convoys are completed well within the legal limit for drivers' hours. The lorries do not exceed the 60 mph motorway limit because the convoy moves at the speed of the slowest vehicles.

The convoys have clearly been a welcome boost for some hauliers — lorries have come from as far away as Cornwall — but for some South Wales hauliers, starved of work and profitable rates for years, the convoys have meant survival, and for the drivers continued employment. The prospect of blacking by miners or dockers after the dispute is irrelevant if you cannot otherwise survive that long.

Hauliers' drivers who refused to carry coal into Llanwern would in effect be sacking themselves. And they would not get anything like the redundancy payments, amounting up to £30,000, which are being paid to miners. If they did, many of them would probably take redunciancy! The effects of the miners' strike on hauliers will not long be remembered by the public at large, not even the crucial role which the flexibility of road transport played in maintaining a lifeline to Llanwern and quite possibly saving thousands of jobs.

What will be long remembered, however, is the role of Gloucestershire hauliers George and Richard Read, the only employers in the dispute to use the Employment Act 1980 against the NUM.

They have been accused of being "put up to it" by the Institute of Directors, a charge they strongly denied when I visited them. One thing is certain, they stepped firmly on ground on which the BSC, the RHA and many hauliers feared to tread. In talking to CM, the Reads told me to leave their drivers out of it, as it had nothing to do with them. "It was our decision and we will take any flak from the miners," they said.

After being caught up in industrial disputes for 30 years, hauliers at last had the law on their side for the first time, they said. The absolutely fundamental point behind their action is that the miners' action in picketing the steel works was unlawful and illegal. It was secondary picketing of hauliers and their customers, neither of whom were involved in the mining dispute.

In using the law, the Reads said, they were ensuring that they could operate their business. "In no way were we motivated politically or by any other person whatsoever. We're not union bashers. The picketing had reached a peak, with our lorries being prevented from leaving Port Talbot for 20 hours."

(It should be added that the Reads get none of the £50,000 fine imposed by the court for contempt.) "We didn't really know what the repercussions would be, but we realised we could be blacked afterwards. We took the action in the interests of jobs, safety, and our business. It was necessary for somebody to take a stand.

"Every haulier in the country is going to have to face the same decision at some stage, and I hope your article helps them," George Read said.

Hauliers I spoke to involved in the lorry convoys, who did not want to be named, feel that the court action taken by the Reads did have a moderating effect on the NUM in South Wales. Certainly, the picket lines have been much quieter in recent weeks.

Having successfully won an injunction against the NUM, George Read has been tempted to take similar action against the TGWU following blacking of his lorries by dockers, on local initiative without official backing of the union. Many hauliers fear that this could lead to a national docks strike.

There appears to be an important difference between the two circumstances, leaving aside long-term consequences. If a union is already on strike, as was the case with the NUM, there is little they can do in immediate retaliation, either with official or unofficial support. If, on the other hand, a court action is taken against workers who are then provoked to take strike action, the firm which took the action is going to lose popularity all round. On the other hand, he has little to lose if he is unable to work anyway.

Union attitudes are obviously going to be important after the strike, although some hauliers would argue that much of what senior officers say is at the best of times bluster. There is no doubt, however, that the TGWU believes its haulage drivers' section is being strengthened by the miners' strike, and that it intends to work closely in future with the NUM.

South Wales regional secretary George Wright, the man at the centre of the TGWU's handling of the miners' strike, told me: "It's the best thing that has happened to us in ages. We have had a tremendous upsurge in membership. We will not come out of the miners' strike as weak as we went in.

"With the South Wales miners' funds frozen (following the Reads' injunctions) the whole situation is very much more turbulent in this region."

Mr Wright made several points clear as to the union's intentions. The union will use its increased strength to help clean up the industry. And they will not just be dealing with hauliers, either, but will "put a stop to the antics" of their customers. Particularly, he singled out BSC and the NCB. "We shall stop some of the under-cutting that goes on," he stated.

"These employers have made the mistake of exploiting a temporary situation. 'Scab' hauliers will be excluded," he warned. 'We are not fools, we are not crude or brutal — but we are strong."

The haulage Joint Industrial Council, which fell apart two years ago, would be reformed, he predicted, as relations between the union and most employers improved. "They will want the protection of the JIC."

He attacked particularly the BSC, whose senior management he described as "zealots" for Thatcherism. "They are front men for the Government and they will discard the hauliers once this is over. The BSC is playing a very dirty, very nasty political game."

Mr Wright predicted that the TGWU will expel some drivers who have been carrying traffic which would normally go in by rail, for breach of an instruction from the General Executive Council of the union not to carry coal or coke.

Other drivers will be "excluded" by the regional committee of the union. This is a form of discipline for which no reason has to be given and against which there is no appeal, Mr Wright said. He refused to define what the term meant, although I took it to mean the same as expulsion, and I could find no mention of the term in the TGWU rule book.

The toughest action will be taken against drivers who volunteered for scab traffic beca use of the high rewards offered, Mr Wright told me. Pressure on hauliers and drivers will be taken into account.

What will be the consequences of losing union membership? "This is an area which is highly unionised. Work out the consequences for yourself."

TGWU haulage drivers' leader Geoff Jacob, who is to some hauliers as a red rag is to a bull, told me: "The hauliers who do not live and work in South Wales do not understand the problems that exist. You have to live in a mining community to understand."

Around 1,000 of his members are out of work at present because of the strike, and are drawing unemployment benefit. But neither they nor the hauliers are complaining or arguing, because of the community in which they live.

The fact that drivers have been laid off does not mean they have lost their jobs permanently, Mr Jacob said, although he agreed that some would not get their jobs back. If the miners do not succeed in their strike there will be job losses, he said. And he added that Llanwern steel works would not close whether it gets coal deliveries or not.

Mr Jacob predicted effective blacking action by the NUM after the strike. The Iron and Steel Trades Confederation let down many reputable hauliers and their drivers after the 1980 dispute by refusing to black companies which had gone through picket lines. "The NUM is a different animal from the ISTC," he warned. "The NUM attitude is hardening daily," he said.

"The NUM is a good ally for haulage drivers, and will continue to be. The miners' dispute has to do with both dockers and drivers," he added. "You cannot be a fair weather trade unionist."

Just how may trade unionists, particularly in Mr Jacob's branch of the TGWU, feel they want to stand at the prow of the union's ship taking the brunt of the rough weather remains to be seen — and they may not all share the union's belief that they should be prepared to risk losing their jobs, with little or no redundancy pay, in support of the miners.

They may be none too happy at the idea of being disciplined for crossing an illegal picket line.

It is hard to believe that there will not be some changes as a result of the exhausting strike in South Wales. Life will certainly never be the same for those hauliers who have lost their livelihood and those who have laid up their lorries and survive the strike rather than risk blacking may be hoping to clean up.

But just what will be the lasting effects of the strike, is unanswerable. Nobody knows.