A LIMITED-ACTION DIFFERENTIAL GEAR.

Page 20

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

An Interesting Device with Certain Novel Characteristics.

NUMEROUS efforts have been made from time to time to design a differential gear which shall be simpler and cheaper to manufacture than the pinion type, which is so largely employed. Slipping clutches, wedging devices, ratchets which permit overrunning of the wheels, have all been tried, but most of them have not stood the test of long-continued work on the road, A new type of gear has been designed and patented by J. H. Stott, B.Sc., of Glen May, Osmaston Park Road, Derby, and this, whilst being extremely simple, embodies features of such ineterest that it merits the attention of manufacturers and users. It ants on the principle of permitting one wheel to over-run the other as required, but this action is limited,the actual over-running being slightly under two turns of the wheel. The gear can be fitted in the normal position within the central casing containing the final drive gearing, or it may be incorporated with the hubs. It is not intended that it should be fitted to existing vehicles unless these be radically altered so far as their rear axles are concerned.

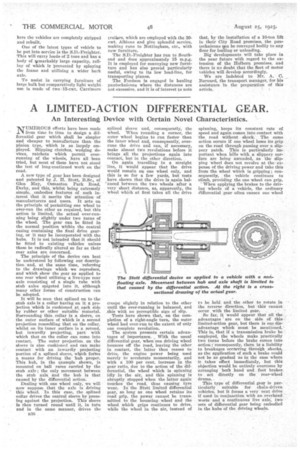

The principle of the device can best be understood by following our description, and, at the same time, referring to the drawings which we reproduce, and which show the gear as applied to one rear wheel utilizing a live-type rear axle consisting of a single tube with stub axles spigoted into it, although many other forms of construction can be adopted.

It will be seen that splined on to the• stub axle is a collar having on it a projection which is cushioned at each side by rubber or other suitable" material. Surrounding this, collar is a sleeve, on the outer surface of which is a second projection resembling that on the collar, whilst on its inner surface is a second, but inwardly projecting, part with which that on the collar can come into contact. The outer projection on the sleeve is also cushioned and can make contact with an inwardly projecting portion of a splined sleeve, which forins a means for driving the -hub proper. This hub, in the example shown, is mounted on ball races carried by the stub axle ; the only movement between the stub axle, end the hub is that caused by the differential action.

Dealing with one wheel only, we will now suppose that the axle is driving this wheel. In this case, the splined collar drives the central sleeve by pressing against the projection. This sleeve is then turned round until it, in tutu and in the same manner, drives the

B38 splined sleeve and, consequently, the wheel. When rounding a corner, the outer wheel begins to run faster than the inner wheel and, consequently, overruns the drive and can, if necessary, make almost two revolutions before it brings , all the projections again into contact, but in the other direction.

On again travelling in a straight line, it would appear that the drive would remain on one wheel only, and this ie so for a few yards, but tests have shown that the drive is again bal'lanced between the two wheels after a very short distance, as, apparently, the wheel which at first takes all the drive creeps slightly in relation to the other nntil the over-running is balanced, and ..this with no perceptible sign of slip.

Tests have shown that, on the completion of a right-angIe turn, the outer wheel had over-run to the extent of only one complete revolution.

The system presents certain advantages of importance. With the usual differential gear, when one driving wheel bounces off the road, leaving the other in contact, the latter then ceases to drive, the engine power being used merely to accelerate momentarily, and with a 100 per cent, increase in the gear ratio, due to the action of the differential, the wheel which is spinning idly in the air, and this spinning is abruptly stopped when the latter again touches the road, thus causing tyre wear. In the Stott limited differential gear, so long as one wheel retains its road grip, the power cannot be transmitted to the bouncing wheel and the wheel which grips continues to drive, while the wheel in the air, instead of

spinning, keeps its constant rate of speed and again comes into contact with the road without shock. The same action occurs if one wheel loses its grip on the road through passing over a slippery patch. This is particularly important when hills with a slippery surface are being ascended, as the slipping wheel does not revolve at the expense of the driving power and take this from the wheel which is gripping ; consequently, the vehicle continues to climb, providing the one wheel can grip. —When applying the brakes to the driving wheels of a vehicle, the ordinary differential gear often causes one wheel

to be held and the other to rotate in • the reverse direction, but thig cannot occur with the limited gear.

So far, it would appear that all the advantages are on the side of this limited-action gear, but there is one dise advantage which must be mentioned. This is, that if a transmission brake be employed, the wheels make practically two turns before the brake comes into action; consequently, there ig a liability to breakages occtsrring throu'gh shocks, as the application of such a brake could not be as gradual as in the case where it takes effect immediately, but this objection would be entirely overcome by arranging both hand and foot brakes to act directly on the rear-wheel drums.

This typo of differential gear is particularly suitable for chaliedriven vehicles, but it forms a very neat drive if used in conjunction with an overhead worm and a continuous live axle, two sets of differential gear being embodied in the hubs of the driving wheels.