Managers leave drivers

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

holding the baby By bin Sherriff AS a young traffic clerk I was counselled by an old and experienced driver : " Laddie, there's more in planning the job than doing it," words I recalled many times during my recent trip to Tehran, as one obstacle after another had to be surmounted. Some were overcome first time, others after many attempts — most of them mainly through the drivers' experience and native wit and some "unaccountable" expense.

With planning, most of the problems could have been avoided and a job that in the end could only have washed its face would have paid handsomely. If it has paid at all now it must have been overpriced in the first instance ; it took six days more 'than it need have done.

I travelled with three Eastern BRS units hired with drivers to U&B Transport Ltd, of Cambridge, and hitched up to ICS trailers loaded on behalf of Trans Asian Express of Camberley with crushing equipment and graders for road making. The traffic was passed to Trans Asian by Kiihne and Nagel, the shipping and for warding agents.

An operation involving so many parties is fraught with danger because the responsibility passes from one to the other and seems to finish with the drivers. This is not so in fact. It is always management's responsibility to ensure that the men who are carrying the goods do not carry the can. Authority can be delegated, responsibility cannot.

On such a journey, the route and timing must be planned, the men must be briefed, documentation inspected, currency properly allocated, ferries booked and confirmed, agents along the route contacted. The men should 'at least be advised of overnight accommodation and servicing facilities en route, and equally important, they must have a few days' warning of their departure day.

Guidelines

It was failure to follow these guidelines which caused most of our unnecessary problems. Before I left, Peter Thompson, chief executive of BRSL, had told me that this was one of two-route proving trips that Eastern BRSL had organised using BRSL drivers. He knew there would be equipment and technical difficulties, so the company had decided to concentrate on this aspect. He added : "We're leaving the provision of loads and permits to established operators on the route."

In the event, lots went wrong but similar troubles attended the activities of other longer-established operators whose drivers I spoke to between here and Tehran.

First of all the documentation. No manager has the right to expose drivers to the threat of imprisonment or fine because he has failed to inspect permits and carnets or has knowingly or unwittingly issued false documents.

Our permits were delivered to the ferry office in a sealed envelope addressed to U&B Transport.

We learned from -the DOE on our return, to the surprise of both U&B and Trans Asian, that the German, Austrian and Yugoslav permits for the load hauled by the Scania 110 in our convoy were false.

Had this not happened, we would have saved E200 over the three vehicles. This was the cost of the ton-kilometre tax and other expenses to get new permits in Yugoslavia.

To add to this, these new permits expired on April 1 and this caused further delays in Tehran while return permits were obtained.

The original permits for all three countries and all three vehicles had been made out in the name of a company unconnected with the operation and one was date stamped as issued on a Sunday !

Had the route been properly planned, no question of any false permits would have arisen. Road/rail permits for transit in Germany are readily available and Austrian and Jugoslav transit permits are granted almost automatically on application.

The cost of using the German road/rail system is 1060DM. This covers the return 900km (562m) journey and gives sleeping accommodation for two drivers.

Using this method means that the driver can cross Ger many comfortably and without any problem in one day's driving. Crossing on the overnight ferry to Ostend, crossing into Holland and into Germany at Aachen, and travelling on to Cologne for the night train, gives the driver 12 hours to clear two customs posts and 100 miles.

It takes six hours to cover the journey from Cologne to Stuttgart and thereafter it is autobahn all the way to the Austrian border at Salzburg.

Couchette

The train journey begins at 7.30pm and ends at about 2am. During this time the driver is provided with a couchette in which he can rest. He should arrive at the Salzburg customs at about Sam and even on the busiest day should be well clear of the border before midday. This would leave him ample time to cover the 140 miles to the Jugoslav border over the " Ho Chi Min trail " —the drivers' name for the Salzburg-Graz road — before 8pm.

Thus the Jugoslav border is reached 48 hours after leaving the UK.

In our case this part of the journey took four days, even though hours and speed regulations were not always obser ved; there was also a frustrating 36-hour delay at the Salzburg border. This customs post closes for goods vehicles from 3pm Saturday until 8am Monday. Good pre-planning could have avoided this.

On the road to Salzburg one of the Crusaders' trailers blew a tyre. According to the Michelin agent, the damage was irreparable. The replacement at Salzburg cost £177 of the driver's running money.

Another driver, Bob Hawkins, who was out of the UK for the first time in his life, had joined our convoy. He was employed by F. W. Flower, of Dorset, carrying for Cantrell Ltd of Bow, East London. His unit was a DAF 2600 pulling a Rentco trailer. He also blew a tyre. When it was stripped, it was found that a previous sidewall damage had been " repaired " by inserting a piece of conveyor belting. The friction between the tube and the belting caused the puncture. This tyre was also irreparable but since Bob Hawkins was on his own and had only E300 running money, he could not afford to replace it, With more than 2,000 miles to travel, he was running short of cash and had no spare wheel, Crossing Austria caused us little problem, even though it later transpired that our transit permit was false.

Getting out of Austria proved our most difficult hurdle. On examination of their carnets, •the drivers found they had to by-pass the Maribor customs, travel a further 20 miles and cross the border at Radkersburg.

The drivers nevertheless chose to cross at Maribor. The Jugoslav permits were compared with others in the precustoms car park and the BRS drivers decided not to present theirs but to pay the optional ton-kilometre tax instead.

Although this method is allowed for in the AngloJugoslav bilateral agreement, that very day the Jugoslays had chosen to rescind it and we were turned back.

Bob Hawkins, the non-BRS driver, presented the permit with which he had been issued The customs officers claimec it was false, together Wit!' one presented by anothei driver, John Hastie, who was driving a BRS unit (not in our group) for U&B Transport. Only by very strong pleas of innocent involvement did the men escape the imprisonment which the Jugoslav border authorities immediately threatened.

All five vehicles were turned round in "no-man's-land," and so five days out we were 700 miles away from the base and facing back towards England again.

Cup of tea

I suppose the right thing to have done was to start up, head for home and place the responsibility where it properly lay, on the managers' desks. But the drivers applied the British solution to the problem. They made a cup of tea and had a chat.

The outcome of the discussion was to contact t h e Embassy in Belgrade, but the drivers did not have the Embassy telephone number. In fact they did not have any Embassy telephone numbers for the seven countries through which they would be travelling. I remember wondering how a man could be sent 3,400 miles from home without knowing how to contact his one sure link with Britain. Fortunately, I had the Belgrade number.

It seemed, however, that circumstances were s till against us. The telephone line between Maribor and Belgrade was down, so I volunteered to return from " no-man's-land " into Austria as a pedestrian to find an agent willing to help. Here again, a previous arrangement with an agent on the border would have proved invaluable.

British agents with offices at the Maribor border please note: your people either turned us away or ignored us completely. The man who eventually helped was the agent Hans Bras, who, on hearing our plight, made his telephone available.

I think I shall always remember the name of "our man in Belgrade." Mr Legge could not have been more helpful. It was he who arranged for the issue of five new transit permits. He waved aside expressions of gratitude. "We're used to it, Mr Sherriff," he said. "It's happening all the time. There are five men at the Eastern border at Dimitrovgrad waiting for return permits but it looks as if they have been lost in the post."

In that event, could we come and collect ours ? "Of course," he said. "But go to Maribor first, and see the senior customs officer and ask for permission to travel with the five vehicles to Belgrade to collect the permits."

Dash by taxi

A taxi dash over the 10km to Maribor proved fruitless, The customs officer goes off duty at 3pm ; I arrived at five minutes past. Back again at the border we contacted the Embassy and the outcome was that John Hastie and I set off to Belgrade by the night train to pick up the permits from the Embassy night security guard, returning by the same train next morning back to Maribor. We were assisted on this part of the operation by a driver, Bill Hill, who provided transport in his Leyland Marathon demonstrator which he was delivering to the Belgrade Show. The Marathon served as a taxi to the border and the railway station.

Another 36 hours had been lost by our group quite unnecessarily because someone had provided unacceptable permits. While I was at Belgrade, two more British vehicles arrived at Maribor with permits which were also rejected. After their drivers had contacted the Embassy they were directed to Zagreb to pick them up. I am ashamed to report that only British drivers appeared to be suffering this indignity—foreign trucks were passing through all day.

Shifting load

Crossing Jugoslavia there were no further documentation problems but, again, lack of adequate supervision in the pre-trip arrangements manifested itself in the form of a shifting load. The cargo carried on the Scania artic was two 9-1-ton crushers and at first the driver felt that a piece of 91 tons was much too heavy and well secured to move. Until now the roads had mainly been of autobahn standard. However, an ominous bulge in the trailer tilt became too prominent to ignore. He nursed the pregnant trailer along, dropping speed, cornering with great care, taking roundabouts at a snail's pace and all the time losing precious hours. At the Bulgarian border, he doubleroped the tilt across the offending bulge. It was a Canute-type gesture and proved of little avail.

Grateful

Next morning, as we made painfully slow progress around Sofia, it happened. I suppose the driver should be grateful that the Bulgarian traffic police do not allow heavy goods vehicles through city centres, otherwise he might now be facing charges of manslaughter.

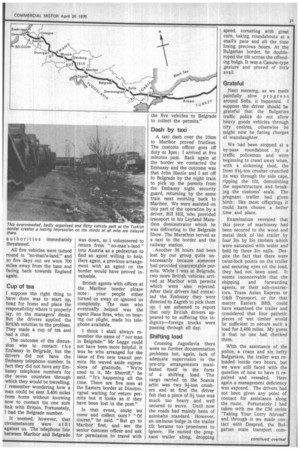

We had been stopped at a by-pass roundabout by a traffic policeman and were beginning to crawl away when, with a sickening thud, the front 91/2-ton crusher crunched its way through the side cape, ripping the tilt, demolishing the superstructure and breaking the customs' seals. The pregnant trailer had given birth : like most offsprings it could have chosen a better time and place.

Examination revealed that this piece of machinery had been secured to the wood and metal deck of the trailer by four 3in by 2in timbers which were saturated with water and held by three 3in nails. Despite the fact that there were twist-lock points on the trailer and securing eyes on the load, they had not been used. It seems inconceivable that the shipping and forwarding agents, or their sub-contractors, Trans Asian Express or U&B Transport, or for that matter Eastern BRS, could have examined the trailer and considered that four pathetic pieces of wet timber would be sufficient to secure such a load for 3,400 miles. My guess is that no one had checked them.

With the assistance of the police, a crane and six hefty Bulgarians, the trailer was reloaded inside two hours, but we were still faced with the question of how to have it repaired and resealed. Here again a management deficiency was exposed. The drivers had not been given any point of contact for assistance along the route. Fortunately I had taken with me the CM series "Taking Your Lorry Abroad" and through it we made contact with Despred, the Bulgarian state transport cam continued from page 31 pany.

Des pred telexed the news to Eastern BRS and put the repairs in hand; they agreed to reseal the vehicle under customs supervision. By the time all this had been arranged another day had been lost quite unnecessarily.

Frayed nerves

The drivers' instructions from England were that the Scammells should proceed while the Scania waited for the repairs to be completed. That night was spent convivially at a Bulgarian motel repairing frayed nerves and tempers, but next morning we had another setback. Before breakfast the Scania driver announced that he was returning to England by air.

Apparently he had been negotiating a house purchase and had been reluctant to leave at such short notice in the first instance, and did so only in the belief that he would be home in five weeks' time. The successive delays clearly indicated a much later return and he was not prepared to lose the house and his deposit. He notified his depot of his intentions and settled down to wait for a relief driver while we proceeded; another 36 hours late.

As we crossed Bulgaria to the Turkish border, the other two loads moved but they remained on the trailers throughout the journey, although it did mean •that there was a significant reduction in speed.

One-mile queue

At Kapicula on the Bulgarian-Turkish border, traffic converged from all over Europe and Asia Minor and we joined a one-mile queue of vehicles in late afternoon. The border closed at 8pm and so another long wait was in prospect. Here again we were unaware that even one night's delay meant the expiry of our transit visa and only because I had booked in at the border motel, and consequently spent more cash, did I escape a reprimand from the Bulgarian officials.

The drivers were equally unaware of this regulation, but in their case the Bulgarian customs officers took the view that the delay could not be attributed to them and said nothing, It seemed that at last the convoy's fortunes were changing. By lunchtime we were at the head of the queue and an hour later we had moved into Turkey—and that's when things went sour again.

The atrocious customs facilities on the Turkish side of the border caused a further five hours delay. Immediately we entered Turkey we were confronted by a multitude of men who all looked the same in their standard issue uniform and black moustaches, waving their arms, blowing their whistles and directing vehicles into any empty space available, irrespective of whether it was large enough or if its occupancy jammed up another lane. Drivers were then ordered from their cabs and sent in search of agents. The result was chaotic.

Efficient agent

On their only other trip through this border, the BRS drivers had found a very efficient agent—Young Turk. For 200 Turkish lira (about £6.50), this man cleared their documentation inside one hour— but because it was Sunday the customs men charged another 50 lira overtime. We could have been on our way within two hours of crossing, but we finally cleared at 7pm and •had one small slice of luck. At the Turkish border the clocks go back and we regained an hour of the days we had lost. The result was that we arrived at Istanbul at around 1 lpm.

Had the drivers been in possession of a detailed route card, they might have decided to stop at one of the motels along the way. As it was, they headed for Londro camping motel at Ancelo, known to drivers as the Istanbul mocamp. It is not the last word In comfort, but after a 16hour day resistance is low and standards are lowered.

Decision

On my return to Britain, Peter Thompson told me that BRSL would be deciding over the next two months whether to inaugurate a regular service to Iran but that this would be done only if the many problems encountered on the route could be overcome by the BRSL group, with its international connections and its links with the newly established NFC company in Iran.

Next week I shall be writing about some more of those problems, encountered after entering Asia Minor and setting out to tackle the final 1000 miles to our destination.