It's a buyers market now'

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IT wasn't so very long ago that operators were faced with long waiting lists when they went to order a new truck. But these days it is very much a buyer's market with deals, super deals and "my deal's better than yours" deals being offered.

There is not so much cash around and more than ever operators need to know what they are getting for their hard earned money. And that is where CM comes in, testing vehicles right across the weight range from light vans to European heavyweights.

Despite the general economic climate a good many vehicles came our way for road test in 1974-75 and this Testers' Twelvemonth sets out to review the year's work.

At the lower end of the commercial vehicle weight spectrum we tested several vans during the year, the first of which was the Mercedes-Benz L306D grossing 3.5 tons.

This particular van dates back to an original design by Hanomag Henschel and features an overhead-camshaft fourcylinder diesel engine driving through a four-speed ZF allsynchromesh gearbox to the front wheels. Our test vehicle had a kerb weight to 1498kg (1 ton 9.5 cwt) which gave a payload capacity of just under two tons.

When taken over the CM Midlands test route the overall fuel consumption was 11.2 lit/100km (25.2mpg) and the ride was extremely good, with very little pitch or roll. Steering was disappointingly heavy but this was perhaps not so surprising considering the forward location of all the main mechanical components.

Forward location of the transmission did have one major advantage in that it enabled a very low floor loading height to be used which, in conjunction with a door which hinged at the top, made loading and unloading very easy.

Another diesel powered van to be put through a CM road test was the Leyland Sherpa. The 1789cc (110cuin) diesel engine in this Sherpa 215 recorded an overall fuel consumption of 9.8 lit/100km (28.8mpg) for a gvw of 2 tons 3 cwt over the stop-start conditions of the light vans test route.

Ride and handling of this Sherpa were a vast improvement over the 1+-litre petrolengined 240 version tested last year but the steering was far too heavy—especially for a local delivery type of vehicle. Surprisingly, no power steering option is available.

Since its introduction into the UK in 1965, the Ford Transit has sold over 300,000 UKproduced units. Early in the year we reacquainted ourselves with the Custom 90 from the extensive Transit range powered by the optional 2-litre (122cuin) petrol engine in V4 configuration, developing 55kW (74bhp).

With this power output the performance was brisk in spite of some oddly chosen gear ratios which, for example, resulted in a maximum speed in bottom gear of 54km/h (34mph)1 Fuel consumption was a disappointment with just less than 20mpg being recorded fully laden. When tested with half the permissible payload on board the fuel consumption was still only 13.3 lit/100km (21,3mpg).

Few middleweights

Most of the vehicles tested by CM in the past 12 months were concentrated at the extreme ends of the weight range, with very little in the middle. One of the few middleweights we managed to get our hands on was the 18-ton Commer Commando artic—the G 1811.

Our memory of this particular test is coloured by manoeuvring difficulty with the trailer on certain of the narrow sections. With a platform length of 12.2m (40ft) and a single axle set as near to the rear as it was possible to be without becoming part of a following vehicle, the outfit was quite a handful.

The power unit was a turbocharged Perkins, the T6.354, which gave 109kW (146bhp) resulting in a power-to-weight ratio of 6kW/tonne (8bhp/ton). This power output permitted a start from rest in second gear of the five-speed synchromesh box (with the low ratio of the Eaton two-speed axle engaged). General performance was good, although the fuel consumption was higher than expected at 30.1 lit/100km (9.4mpg)—but road works and heavier-thanusual traffic on the test did not help in this respect.

• The first three-axle truck to be tested by CM for a long time came our way in April in the form of the Leyland Bison. This uses the naturally aspirated version of the fixedhead Leyland 500 engine in which form it develops 120kW (162bhp).

British Leyland is the leader in the six-wheeler market— by a considerable margin—and the Bison is available in tipper, • mixer and standard haulage chassis form. Our test was of the haulage model with the four-spring rear suspension (as opposed to the patented Leyland T6 two-spring bogie). It was a workmanlike truck which gave a good account of itself on the Scottish operational trial route. Fuel consumption was acceptable at 36.2 lit/100km (7.8mpg) and it could probably have been improved upon with different gearing.

During the trial the six speeds (a basic five-speed box with overdrive) were inadequate, especially at the top end. With the engine revving away heartily in, say, fourth gear it was totally unable to pull fifth.

When a long gradient was encountered — the Loughborough "heavy lorries" section for example—there was no lower gear available until the road speed had dropped to around 40mph. Leyland does in fact have a 10.-speed gearbox as an extra but this really only increases the ratio options in the lower speed range, and the standard six-speed box is already adequate in this area.

Unlucky thirteen?

Once again the maximumcapacity artic category provided the most vehicles for road test. This concentration at the heavy end is not delilnrate CM policy—we merely test what we can get.

This last year has seen no fewer than 13 heavies go round the England-Scotland operational trial route. Before giving a brief summary of the individual trucks' performance, I must say that one particular section of the test procedure revealed some very disturbing results—braking. As regular readers will know we carry out full-pressure braking stops with the fully laden artic com bination at the MIRA proving ground from 20, 30 and 40mph. Some outfits performed well, but time and again this test showed the braking distance to be extremely unsatisfactory and, in several cases, the maximum retardation did not even conform to C & U minimum requirements.

In every case the problem lay with the trailer brakes. If this situation can arise with a vehicle prepared for road test where it is known that full-pressure braking tests will be carried out. One wonders about the efficiency of the trailer brakes on units in everyday use up and down the country.

UK versus the opposition In Testers' Twelvemonth last year, of all the heavies tested only one was from a British manufacturer. The situation improved considerably this year with nearly half the trucks tested being from UK companies-although this is probably stretching a point in the case of the Spanish-built Dodge Barreiros and the Amsterdam-built Ford Transcontinental.

The big Baneiros-or the K3820P as Chrysler prefer it to be known-went very well during our test recording the highest ever average speed (at that time) for the 1172km (728-mile route). With 201kW (270bhp) on tap it was a real driver's truck which took hills in its stride.

Fuel consumption was slightly worse than average for this route at 44.8 lit/100km (6.3mpg) but this was coupled with an excellent round-trip journey time. So far as the operator is concerned, a vehicle which can return high average speeds rather than high mpg could be more useful where distances in relation to drivers' hours are tight.

Mechanical specification was excellent, with the eight-speed gearbox being well matched to the torque curve of the turbocharged engine. But it has an "urban delivery" cab mounted on a long-haul chassis and in this area the Dodge fell far short of its competitors. One advantage of the cramped cab, however, was the ability to couple legally with a 401t trailer.

When we tested the uprated Volvo F88 in February it was a test with a difference-we ran it successfully at 32 tons and 38 tons gcw (the latter with special dispensation as it exceeds current C & U limits). The 88 has been the market leader in the heavy category for some time now and the CM test did nothing to disprove this claim.

Fuel consumption at 32 tons was 43.5 lit/100km (6.5mpg) which increased to48.7 lit/ 100km (5.8mpg) at the higher weight. For the statisticians this meant an increase in fuel consumption of around 11 per cent for a 28 per cent increase in payload capacity. Journey time was scarcely affected by the increase in weight-34 minutes difference in 17 hours. A difference of this order could be caused by heavier traffic on one run.

As with the Dodge the cab was the Volvo's only substandard feature and one wonders how long it will be before a completely new heavy truck cab comes out of Gothenburg, as distinct from a facelift.

With 16 speeds available from the combined rangechange/splitter transmission, the right ratio for the conditions was always available, enabling the maximum use to be made of the engine's performance.

On this subject, I have received a number of letters from drivers during the past year complaining of my enthusiasm for multi-speed transmissions, and I would just like to set the record straight on this point. The main advantage to such a specification is that the engine can be kept in its optimum working range with a consequent benefit in terms of fuel consumption. Taking the F88 as an example, it is not necessary to use all the gears in sequence-in fact, on the level at 32 tons the Volvo started in second low then went to fourth low and I usually only started splitting in the high range of the box. With this multi-speed facility the driver has the choice available—if he wants to use it as a sixor a 16-speed box it is up to him.

The "little" Volvo F86 was also tested during 1975. This tractive unit is one of the lightest on the market at 5.3 tonnes (5 tons 4 cwt) and for our test it was coupled to a lightweight all-aluminium trailer from Welford which enabled the legal payload to reach a very attractive 24.7 tonnes (24 tons 5 cwt), Fuel consumption was the best figure recorded for a 32-tonner since the 8LXB engined Atkinson some three years ago—the actual figure being 38.2 lit/100km (7.4mpg). Although the maximum power of the engine has been raised to 150kW (201bhp) it ig still a marginal figure for 32 tons operation giving a power-toweight ratio of 4,6kW/tonne (6.3bhp/ton). This was reflected in one of the longest journey times for the Scottish route. It is surprising that a splitter option is not available on the 86 as it would make very good use of one.

The star of the show at Earls Court last year was undoubtedly the TM range from Bedford and it was with great interest that we awaited the first heavy from GM for road test. We tested the TM 3250 designed for a gcw of 32.5 tonnes (32 tons) and powered by a two-stroke Detroit Diesel 6V-71 engine which produced 161kW (216bhp).

The cab was extremely comfortable and the ease of handling was impressive. Bedford, like many other manufacturers, has opted for one of the Fuller Roadranger gearboxes—in this case the RTO 609.

This is an excellent gearbox whose ease of action has been ruined in several trucks by a sloppy selection linkage. The Bedford, however, had the best gear selection mechanism I have ever come across with a Fuller so it does show that it can be done.

The Detroit Diesel is not a familiar engine to British operators although it has been well proven in America. Its overall fuel consumption was rather disappointing at 45,6 lit/100km (6.2mpg) but in all other respects the testing staff like the TM.

Our test of the new Seddon Atkinson again departed from normal CM practice in that we tested it twice. However, unlike the Volvo F88 test this was not strictly intentional.

Test one involved a run through France, Germany and ,Belgium for a total of 1095km (680 miles) including all types of road conditions. The performance of the truck— powered by a Cummins NHC-250—was excellent in the lower, gears and up hills but on level roads it just ran out of steam completely at about 45mph.

The fuel consumption confirmed that something was definitely amiss as the overall figure of 64.2 lit/100km (4.4 mpg) could only be considered disastrous. This engine problem also affected acceleration and the Seddon Atkinson took no 1ess than 99 seconds to reach 40mph from rest.

Cummins had a look at their part of the truck and discovered various problems in the fuel injection system. After adjustment the truck performed extremely well, returning satisfactory average speeds and fuel consumption on our Scottish route. To illustrate the effect of the engine problem, the acceleration time to 40mph was slashed from 99 to 54 , seconds, With its modern cab I think the 400 series will have a successful future.

Tested in early February the 12-speed version of the Magirus Deutz 232 16FS had to contend with rain, snow and blustery winds, which did not help it to return a good journey time. The driver comfort of this truck was good, especially in the ride department, with the specification including anti-roll bars and dampers on each axle.

In spite of the Magirus' failure to restart on the 1 in 5 test hill at MIRA, all the severe gradients on the northern section of the Scottish route were climbed successfully. Even allowing for the appalling weather conditions on this test, the fuel consumption was still high with an overall figure of 47.1 lit/100km (6.0mpg).

The Magirus did reasonably well on the A-classification roads—it was the motorway fuel consumption that spoilt the overall economy picture.

The French company of Berliet has dabbled in the British market before but is now making a serious attempt in sales penetration with the TR280. The engine in this truck has a high torque rise characteristic which provides an almost constant maximum horsepower between 1400 and 2200rpm. This engine specification allowed the number of gear changes to be reduced considerably, especially on the motorways, when there was rarely any need to drop a gear even on the steeper inclines.

The Berliet cab has long been considered one of the best available in terms of comfort and noise insulation. It is significant that when Ford shopped around for proven components for the Transcontinental they chose the Berliet cab.

Overall journey time for the TR 280 was satisfactory and the fuel consumption of 43.5 lit/100km (6.5mpg) was about par for the course.

One of the most impressive heavy trucks ever tested by CM was the Mercedes-Benz 1626 from the New Generation range fitted with the "small" environmental cab. Powered by the V8 OM 402 engine of 188kW (256bhp) this truck returned a magnificent figure of 39.8 lit/100km (7.1mpg) for the 1172km (728 miles) along with what was at the time the shortest-ever journey time. But the list price of the Mere put it in the "super-premium" category.

As with many other artics tested during the year the 1626 had problems with braking, but the reason for this was rather more unusual. The load-sensing valve on the tractive unit had been set for the Continental wheelbase and springs (the UK version is shorter).

It was coincidence that the " small " Mercedes-Benz was immediately followed by the " big " Ford Transcontinental, emphasising the opposing views on design from the two factories. We tested two Transcontinentals during the year, both in artic form.

The first was one of the most powerful of the range, the HA 4231 designed for operation at 42 tonnes with a 310bhp engine-hence the type number. Although the truck was impressive it was like a fish out of water at 32 tons gross to UK limits.

The frontal area imposed by the fridge box on the test Combination did not help in terms of aerodynamic drag and this was reflected in the poor fuel consumption of 47.9 lit/100km (5.9mpg). But with this high power output available the Ford returned the highest average speed ever recorded for the Scottish operation trial route-still standing at the time of writing.

The lighter HA 3427 was a much better proposition, with various weight saving measures the sleeper cab is standard -including removing the bunks and fitting low-profile tubeless tyres-bringing the kerb weight down to 6.9 tonnes (6 tons 16 cwt). But even at this weight it was still a heavy truck. The combination of a more suitable specification and a flat trailer resulted in the much improved fuel consumption of 43.8 lit/100km (6.5mpg).

The cab of the Transcontinental must be about the most luxurious on the scene at the moment. But because equipment it is not possible to couple to a 12.2m (40ft) semi-trailer and stay legal unless the trailer has a nonstandard 1.2m (3ft 1 lin) kingpin position, which could mean interchangeability problems for some operators.

Like the Leyland Bison we waited a long time to test the Buffalo, but it was certainly worth waiting for as it performed very well indeed. Powered by a turbocharged version of the same 500 engine fitted to the Bison which gave 158kW (212bhp) the Buffalo achieved an excellent fuel consumption figure of 38.7 lit/ 100km (7.3mpg).

With the light kerb weight of 5.6 tonnes (5 tons 10 cwt) the Buffalo also had an excellent potential payload capacity. The good fuel consumption was not achieved by driving gently as the overall average speed was equal to the opposition. One of the problems with the Buffalo (and the Bison) is that the cab can only be tilted to to 30' and that involves removing the driver's seat.

CIVI's road tests of Scania vehicles have often been beset with difficulties, and the LB 111 was no exception. Because of a severe trailer braking problem the test was abandoned half-way round for safety's sake. This was infuriating as the truck itself, which is, after all, the part we were most concerned with, had performed creditably up to that point.

The noise level in the cab was very well controlled and, when cruising at the A road limit of 40mph, no engine noise whatsoever penetrated the cab. On the test vehicle the gear ratios were oddly spaced and would have been more use in an on/off road tipper, the gears in low range being far too close together. For what it is worth the fuel consumption of the Scania for the abbreviated test was 45.5 lit/100km (6.3mpg).

The latest Saviem to be imported into Britain—the SM 36-280—provided one of the surprises of the year. When we tested the 240 version some 18 months ago the general concensus of opinion was that it was an excellent truck which would benefit from the addition of a few extra horses. The 280 was powered by a turbocharged version of the 240's power plant giving it a 20 per cent increase which completely transformed the performance.

Journey time for the turbocharged truck was cut considerably at the same time as returning a fuel consumption of 42.9 lit/100km (6.6mpg). Although we expected an improvement, the increase was greater than we had predicted.

Three eight-wheelers

After a dearth of four-axled rigids during recent years, three such trucks have recently been made available for test, all in tipper form, from DAF, Seddon Atkinson and Volvo. The DAF specification 'included the DU 825 turbocharged engine developing 159kW (216bhp) driving through the complicated Fuller RTO 613 13-speed gearbox. "Complicated," as this box must have the most tortuous shift pattern ever invented, but it certainly allowed the vehicle's performance to be fully exploited. Cab comfort and handling were good.

An all aluminium Wilcox body on the DAF permitted a very useful payload of just under 20 tons. For an eightwheeler with a 6.3m (20ft 6in) wheelbase the DAF had a surprisingly good turning circle of under 70ft.

The Seddon Atkinson was tested with a Cummins engine installed and although the fuel consumption was satisfactory it was probably not good enough to tempt operators away from the Gardner, which is so popular for home-built eight-wheel tippers.

This truck also had a good turning circle for its type and the general handling was pleasing. Unfortunately due to a loading problem unconnected with the vehicle it was not possible to run at the full 30 tons gvw (the actual all-up weight was just over 28 tons) but it romped up steel gradients with its 6.5 axle ratio.

The Volvo eight-wheeler is based on the mechanical components of the F86 with the addition of the rear bogie from the bonneted N-series. Fuel consumption was very good as would be expected from the TD 70 engine, and a comment that perhaps a choice of a lower axle ratio might be useful for on-site work has been answered by Volvo, who have said that a 6.1 to 1 ratio is available if required (compared with the standard one of 5.43).

Productivity

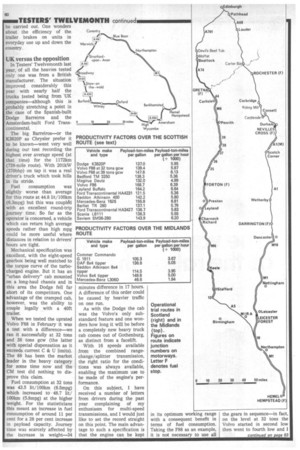

In Testers' Twelvemonth we like to compare productivity factors based on the figures obtained during CM road tests. In the tractive unit category, because the trucks tested during the past year were coupled to a variety of trailers of widely differing weights, we have substituted an estimated " average" trailer weight to provide a basic datum on which potential payload capacity can be evaluated.

In actual fact the trailers used to gross 32 tons varied in weight from 2.44 tonnes (2 tons 8 cwt) for the allaluminium Welford to 5.4 tonnes (5 tons 6 cwt) for a Crane Fruehauf T1R tilt. In view of this we have used a standard unladen trailer weight of exactly four tons. The kerb weights for the tractive units are those of the actual test vehicles from a weighbridgethey are not the manufacturers' estimated figures.

Depending on the type of work involved, different operators have differing requirements. Because of this, comparison of the trucks is on a payload-ton-miles-per-gallon basis and also on a payload-tonmiles-per-gallon-per-hour basis.

The former is arrived at simply by multiplying the payload by the average mpg figure. For the latter a specimen calculation based an the Leyland Buffalo indicates the method: Payload 22 tons 10 cwt ( = 22.5 tons) Fuel consumption 7.3mpg Average speed 40.4mph Thus the productivity factor in this case is: 22.5 x 7.3 x 40.4 1000 =6.64 The denominator of 1000 is used purely to make the productivity. factor a more manageable number.

In ton-mpg terms the highest figure recorded was 168.7 for the Volvo while the MercedesBenz 1626 went to .the top of the list when the average speed was included. The full productivity figures are shown in the accompanying tables. One• interesting point which emerges from these calculations is the excellent performance, in both categories, of the "lightweight" 32-tonners, the Buffalo and the F86, both these trucks being designed for 32 tons maximum and not being 38-tonners running light.

As well as on-road tests of goods vehicles this year we had two very different opportunities to make on/off road assessments of vehicles designed for the rough and tumble life. One was a Land-Rover 88 fitted with the Fairey overdrive to provide 16 forward gears; we put it through a full test routine and fully laden over a varied route it achieved 6.82km/1 (19.3mpg) with overdrive •and 6.23km/I (17.6mpg) without overdrive.

As well as climbing a 1 in 3 test hill in 2nd low the vehicle revealed good roadholding and cross-country abilities, but the brakes were unpleasantly heavy.

For our other on/off road trial we assembled three 16 ton-gross tippers on a con struction site and ran a searching group test with our own drivers. The Commer Com mando G1611 with 109.7kW (147bhp) Perkins T6.354 was a lively performer and returning 3.2km/1 (8.9mpg) over the fairly difficult route, but we found the engine very noisy and the six-speed gearchange sloppy to use.

The Ford D1614 returned 3.0km/1 (8.4mpg) over the same route and was slightly faster over the road than the Commer despite having 4bhp less. The Ford was a comfortable, quiet machine but when a front tyre punctured we couldn't get the supplied jack under the axle -beam.

Third of the tippers was the Leyland Clydesdale, very quiet in the cab and fitted with well positioned controls. With the 98.5kW (132bhp) engine it achieved 3.6km/1 (10.3mpg) over the site test route at the same average speed as the Commer.

Our other group test of the twelvemonth was very much on the road : we took four British panel vans, laden, over our suburban trial route. The Bedford CF22cwt impressed us most on all-round merit; it returned 6.5km/I (18.4mpg). The Leyland 240 (now Sherpa) with 1.8-litre petrol engine achieved 7.1km/1 (20.3 mpg) and was quiet and lively but some driving controls were a little awkward.

The Ford Transit 90 supplied was grossly overgeared for local running and had rather fierce brakes, but it returned 6.4km/1 (18.2mpg) and had good driver access. The Cornmer PB2500 was praised for its light, precise steering but criticised for a cramped driving position. It was economical at 6.8km/1 (19.1mpg) over this special route.

Few psv tests

Although we carried out full road tests on only three passenger vehicles in the year, we were able to try several others in typical operating territory. Included in these was the important Lucas city-centre electric midi bus. After riding on a record-breaking run from Birmingham to Manchester under its own power, we were able to try the bus over its Manchester service route. The converted Seddon bus handled well and its performance was more than adequate for the arduous terrain encountered.

One of our three full tests was of the new Mercedes 0.303 which we tested in Germany in both manual and automatic forms. At well over f40,000 the coaches were some of the most expensive vehicles we have ever driven, but by and large lived up to their manufacturer's very high claims. Over a test route which included part of the Black Forest, fuel consumption was only 0.7 lit/100km (0.3mpg), worse on the automatic than the manual.

The two British psv were run over our Midlands routea Bristol and a Ford.

The Bristol was fitted with a 33-seat PIaxton Supreme body and powered by the naturally aspirated Leyland 401 engine mounted horizontally under the floor.

The overall fuel consumption of 20.6 lit/100km (13.7mpg) for the 103kW (138bhp) coach can be compared with the 22.6 lit/100km (12.7mpg) for the 6-litre turbocharged unit in the Ford over the same route.

The 45-seat body on the Ford was the new Duple Dominant bus and the chassis was equipped with Ford's fourspeed synchro gearbox. This specification-now being chosen by many rural bus operators-proved very efficient on test.

One of the most significant developments in CM's testing of commercial vehicles occurred this year: the journal joined forces with Continental transport magazines to undertake long-distance testing of trucks over varied terrain in several countries.

This move-which is in addition to our UK test programme-reflects the increasingly international aspect of transport and will give CM readers a broadening picture of vehicle requirements and capabilities. The Euro Truck Press route covers 3,800km through Belgium, Germany and Sweden.