What the New

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

CHENARD

WALCKER

Will Do

SINCE its appearance at the Olympia Show last month we have been anxious to test the Chenard-Walcker tractor with the new 87 b.h.p. sleevevalve engine, and we were fortunate a few days ago in having one of the latest models placed in our hands for a day's trial.

Apart from its engine the new 87 b.h.p. tractor resembles in all respects the 44 b.h.p. UT model, for 10-12-ton loads, which has sold so well in Britain in the past few years. The new model will haul 15 tons; no 15-ton trailer was available for us to test, but we put a load of 14 tons 14 cwt. 21 lb. on a standard 10-12-ton trailer, and it stood the test well. The tax payable on the higher-powered tractor is only £25, that of the UT model being £21. The price of the tractor tested is 1803 complete, that of the 15-ton trailer being about £370. The secret of the Chenard-Valcker

is that, instead of carrying dead weight to give wheel adhesion, this is obtained by a patent towing pillar, a short, rigid drawbar and special turntable (which has no king-pin), these enabling the driver to transfer as much trailer weight as desired to the tractor without having to leave his scat. Front-end lift is eliminated by imposing this weight in advance of the driving axle of the tractor. We had to tackle steep hills and slippery mud and all we did to get better adhesion was to slide open the glass door of the cab (without decreasing speed) and give the screw

handle a few more turns. For manceuvring in confined spaces the turntable is locked and the trailer front wheels are raised clear of the ground— then you have the flexibility of an articulated six-wheeler. •

We noticed that at speed there was no trailer sway and nAbraking or acceleration jerk between tractor and trailer. The reason is that (1). the drawbar is rigid, (2) the driving axle is only about 6 ft. from the leading trailer axle, (3) there is noparting of turntable plates, and (4) the load transference aids stability.

The design is one that makes for safety at speed with a heavy load— provided the brakes be adequate. Naturally, it is the rear wheels of the trailer that need greatest braking power. The trailer we tested had on its rear wheels two-shoe drums 1 ft 6 ins, in diameter and 3i ins, in effective width. The standard 15-ton trailer will have drums of 2 ft. diameter. The shoes are cable-operated (with a simple compensating cross-bar) from ratchet levers on the trailer side and in the cab. The trailer brake, on the machine tested, was also actuated

by a Westinghouse vacuum system, -with the patent valve and reservoir. In addition, we had 131-in. drivingwheel brakes operated by another hand lever, and a transmission brake of 11i-in. diameter actuated by pedal.

With this equipment, and a gross weight of about 201 tons, we could, on a wet concrete road, pull up to a standstill from 29 m.p.h. in 155 ft. (7.1 secs.). The Westinghouse gear needed adjustment, for the application was not prompt enough in response to the lever. The braking distance would have been less, also had we used a 15-ton trailer with 2-ft. drums. From 23 m.p.h. we stopped in 89 ft.

The type of brake fitted is at option of the purchaser, but some form of power brake is recommended.

• Dealing now with speed and the use of the gears. although the sleeve-valve engine is governed at 2,200 r.p.m., it is claimed to have a rising power curve up to nearly 4,000 r.p.m. (as indicated on the acceleration graph reproduced). The governor, however, kept our speed to 36 m.p.h: on the fifth (indirect) gear, the ratio of which is very high, namely, 3.67 to 1. With a first-gear ratio of 38.85, the range is a very wide one, and ordinarily bottom gear need never be used for starting on the level. In fact it was easy to get away on fourth gear.

The gear change is particularly easy and the gate and lever are wed placed. All pedals are light in action, also the steering, and . the sprung steering wheel is very comfortable ; altogether the riding qualities of the outfit are excellent and there is. no noticeable engine vibration.

The indirect gears hum a little, but not objectionably. We are told a new gearbox with shorter shafts and roller bearings will shortly be available.

It is quite impressive to be driving a 20-ton outfit comfortably at 86 m.p.h., but what surprised us was the way our speed on the level helped Hs up hills, the impetus being considerable and often saving a gear change. The small dead-load factor is, of course, a very important advantage.

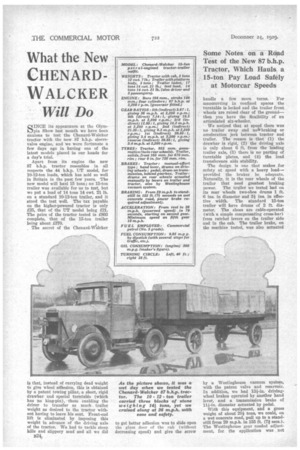

Thi turning circle is very small, being no more than 40 ft., and the outfit can be turned round in a roadway 14 ft. wide—the minimum being imposed by the trailer wheelbase .(13 ft. 5 ins.), and the width of tractor and trailer standing side by side (presuming there are no walls beside the road). This remarkable point is illustrated in one of the photographs. The outfit tested was 34 ft. 6 ins, long, the platform length being 20 ft. 4 ins. The frame height laden was 3 ft. 9h ins. the

We drove the outfit up Putney Hill, London, at 8 m.p.h. on third gear with the engine governor acting. Later we climbed the hill from Belmont Village to the asylum on Banstead Common, Surrey, a gradient of about 1 in 12, at 45 m.p.h., on second gear, stopping and restarting on the steep incline with ease. Then we drove up Wimbledon Hill (about 1 in 13) on second gear at over 5 m.p.h. It is clear that first gear is practically only needed for startiug on hills and ploughing through diffi

cult ground. After all the hill-climbing that we did there was no overheating of the engine. The petrol consumption, at 9.85 miles per gallon (taken by dipstick), was, we thought, very good.

We tried the outfit on the road only, leaving its crosscountry, tree-felling and treehauling capabilities to be explored on another occasion. It must be mentioned, however, that the tractor, being light, can get through soft and muddy ground alone if conditions be too bad for haulage, and can afterwards pull its trailer load through

with the two-speed power winch (which has a reverse gear and brake, and may even be used while *the tractor is travelling under power). Should the tractor get stuck it Can haul itself out by the winch gear, at the same time driving on the road wheels to prevent the packing of soft carth in front of them.

The general impression which the test gave us was that the outfit was a fast, safe and extremely mobile one, and its economy of operation is particularly attractive. There are not many goods vehicles, let alone 15-tottners, that can average over 140 ton-milts per gallon of petrol—and • that at a cruising speed of 30 m.p.h to 36 m.p.h., and with a correspondingly high average speed. Again, there are not many machines with an unladen weight under six tons that will carry a pay load of 15 tons.

The economy is enhanced by the fact that the tractor can deliver one trailer at destination, uncouple, and be away in a minute with another trailer. The detention of the power unit during loading and unloading is a big factor in the haulage contractor's cost calculations. The outfit we tested has however, the manteuvring advantages of the articulated sixwheeled vehicle, as is clearly explained in an earlier part of this article.

Beardmore (Paisley), Ltd., has recently taken over the sales concession and manufacturing rights for Chenard-Walcker tractors and trailers, and hopes to be in full production at Glasgow in approximately seven months. The company intends to fit, as soon as possible, a Diesel-type engine as an alternative to the petrol engines which are available at the present time.