Want to know what happens 1 you fit a cheap

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

brake pad and then work the brakes hard? Honeywell Jurid has been doing some tests, so CM went along to find out what the outcome was...

Words: Sharon Clancy Do you buy 'genuine' OE parts for your vehicles? Or do you buy cheaper 'OE-standard parts? It that age-old debate, and a particularly hot topic when the parts in question are for safety-critical systems such as brakes.

Some operators fit nothing but OE supplier products, while others simply want a cheaper source of parts, but without having to compromise safety. You would reasonably expect that if you buy OE-standard parts that conform to UN ECE R90 (the standard for replacement friction materials), it would guarantee the pads or linings are of acceptable quality. However, the warning from specialist Honeywell Jurid is that even with R90 approval, many of the brake pads on the market are of inferior quality.

Claims of matching quality are just that — 'claims', says Jurid's technical director, Stefan Ernesti. He adds: "Even pads that have been tested to ECE R90 standards will vary in quality. It depends on the pad supplier and which country did the R90 homologation test. In some countries, it is possible to gain R90 approval with only three or four performance tests. We do 10 tests."

Emesti reckons Jurid knows a thing or two about friction material quality, considering it makes around 6 million CV pads a year and 14 million brake linings, as well as being an OE supplier to 66% of Europe's truckmakers. Jurid aftermarket pads are manufactured and tested to the same criteria as pads made for OEMs.

However, acknowledging that operators would expect them to say that, and with all the claims and counterclaims being rather confusing, Honeywell Jurid decided the only way to refute such opinions was to check them.

As a result, it has conducted tests on more than 1.000 pads from various aftermarket ranges, to find if the claims of "OE-equivalent quality" stack up. It then invited a number of journalists to witness a simulation of the toughest test of the lot: the Alpine descent test.

The Alpine descent test

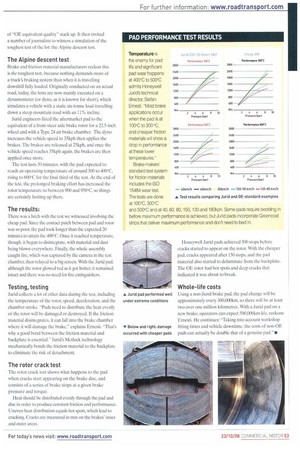

Brake and friction material manufacturers reckon this is the toughest test, because nothing demands more of a truck's braking system than when it is travelling downhill fully loaded. Originally conducted on an actual road, today, the tests are now mainly executed on a dynamometer (or dyno, as it is known for short), which simulates a vehicle with a static six-tonne load travelling down a steep mountain road with an 11% incline.

Jurid engineers fitted the aftermarket pad to the equivalent of a front-steer axle brake rotor for a 22.5-inch wheel and with a Type 24 air brake chamber. The dyno increases the vehicle speed to 35kph then applies the brakes. The brakes are released at 25kph, and once the vehicle speed reaches 35kph again, the brakes are then applied once more.

The test lasts 30 minutes, with the pad expected to reach an operating temperature of around 300 to 400°C, rising to 600°C for the final third of the test. At the end of the test, the prolonged braking effort has increased the rotor temperature to between 900 and 950°C, so things are certainly hotting up there.

The results:

There was a hitch with the test we witnessed involving the cheap pad. Since the contact patch between pad and rotor was so poor, the pad took longer than the expected 20 minutes to attain the 400°C. Once it reached temperature, though, it began to disintegrate, with material and dust being blown everywhere. Finally, the whole assembly caught lire, which was captured by the camera in the test chamber, then relayed to a big screen. With the Judd pad, although the rotor glowed red as it got hotter, it remained intact and there was no need for fire extinguishers.

Testing, testing

Judd collects a lot of other data during the test, including the temperature of the rotor, speed, deceleration, and the chamber stroke. "Pads need to distribute the heat evenly or the rotor will be damaged or destroyed. If the friction material disintegrates, it can fall into the brake chamber where it will damage the brake," explains Ernesti. "That's why a good bond between the friction material and backplate is essential." Jurid's Metlock technology mechanically bonds the friction material to the backplate to eliminate the risk of detachment.

The rotor crack test

The rotor crack test shows what happens to the pad when cracks start appearing on the brake disc, and consists of a series of brake stops at a given brake pressure and torque.

Heat should be distributed evenly through the pad and disc in order to produce constant friction and performance. Uneven heat distribution equals hot spots, which lead to cracking. Cracks are measured in mm on the brakes' inner and outer areas. Honeywell Judd pads achieved 500 stops before cracks started to appear on the rotor. With the cheaper pad, cracks appeared after 150 stops, and the pad material also started to delaminate from the backplate. The OE rotor had hot spots and deep cracks that indicated it was about to break.

Whole-life costs

Using a non-J urid brake pad, the pad change will be approximately every 300,000km, so there will be at least two over one million kilometres. With a Judd pad on a new brake, operators can expect 500,000km life, reckons Ernesti. He continues: "Taking into account workshop fitting times and vehicle downtime. the costs of non-OE pads can actually he double that of a genuine pad." •