100-tonners could do three times the work

Page 25

Page 58

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Volvo's kite-flyer in economy search

From a Special Correspondent

NEVER MIND 38, 40, or even the 44 tons that the more enlightened British wanted for artics back in 1970. If people are serious about wanting to reduce consumer prices and get big savings in fuel they should be thinking in terms of 100-ton road trains.

That is what the Swedish truck maker Volvo thinks, anyway. It has built two 70-ton payload jobs for the oil rush. They are 12-axle doublebottoms powered by two engines. A three-axle tractor is articulated to a tri-axle semitrailer, towing a powered drawbar with tri-axle bogies each end. Each outfit is said to do the work of three ordinary 38-ton artics.

Guidelines

It was with this stirring example of big-payload economy that the Volvo management started an international symposium on transport economy organised at the company's Gothenburg factory last week. After the kite-flying came the more pragmatic stuff.

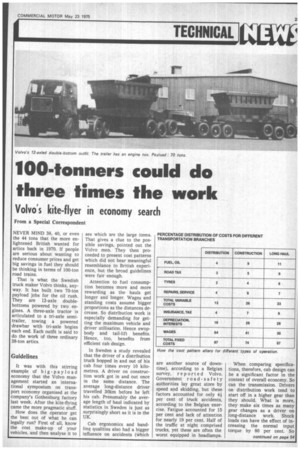

How does the operator get the best out of what he can legally run? First of all, know the cost make-up of your vehicles, and then .analyse it to see which are the large items. That gives a clue to the possible savings, pointed out the Volvo men. They then proceeded to present cost patterns which did not bear meaningful resemblance to British experience, but the broad guidelines were fair enough.

Attention to fuel consumption becomes more and more rewarding as the hauls get longer and longer. Wages and standing costs assume bigger proportions as the distances decrease. So distribution work is especially demanding for getting the maximum vehicle and driver utilisation. Hence swopbody and tail-lift benefits. Hence, too, benefits from efficient cab design.

In Sweden a study revealed that the driver of a distribution truck hopped in and out of his cab four times every 10 kilometres. A driver on construction work got in and out once in the same distance. The average long-distance driver travelled 30km before he left his cab. Presumably the average length of haul indicated by statistics in Sweden is just as surprisingly short as it is in the UK.

Cab ergonomics and handling qualities also had a bigger influence on accidents (which are another source of downtime), according to a Belgian survey, reported Volvo. Government road-safety authorities lay great store by speed and skidding, but these factors accounted for only 41 per cent of truck accidents, according to the Belgian exercise. Fatigue accounted for 15 per cent and lack of attention for nearly 19 per cent. Half of the traffic at night comprised trucks, yet these are often the worst equipped in headlamps. When comparing specifications, therefore, cab design can be a significant factor in the context of overall economy. So can the transmission. Drivers on distribution work tend to start off in a higher gear than they should. What is more, they make six times as many gear changes as a driver on long-distance work. Shock loads can have the effect of increasing the normal input torque by 80 per cent. So

construction work needs a generously rated gearbox.

Can power pay? Theoretically, yes. In practice, mostly no. Legally enforced powerweight ratios came in for a bashing at the Volvo symposium.

NFC figures

The Volvo engineers compared 250hp and 340hp 38tonners and showed that the big engine could pay only if the higher average speed could be translated into more ton miles in the year. Mr Walter Batstone, chief engineer of Britain's National Freight Corporation, was even more specific. He quoted figures from his own big fleet to demonstrate that 280hp was the highest power it was worth going for at the common 72 per cent load factor. The lowest cost per mile was given by 220hp machines. The lowest running cost per horsepower was given by 265 and 280hp vehicles; beyond that the cost became uneconomic.

Maintenance

As far as Mr Batstone was concerned, maintenance cost should be a happy hunting ground for economy-searchers. He had a powerful ally in Mr J. C. "Pat" Paterson, vicepresident, engineering, of the 57,000-vehicle Ryder fleet in the USA. With the aid of computer analysis, Mr Paterson showed just where the money went on maintenance and the scope there was for improving the breed to get those repair bills tumbling.

There was a general impression, Mr Paterson said, that engines accounted for the bulk of maintenance expenditure. Not true in the good old USA, apparently. His computer analysis of maintenance costs over 300,000 miles showed that engines came 11th down the list, costing less than a 10th of preventive maintenance and a quarter of the expenditure on brakes. Starting, fuel and cooling systems, clutches, bulbs, belts, wipers and heaters all accounted for more expenditure than engines.

The study spurred Ryder to request vehicles which would need only one docking a year, automatic oil replenishment, a long-life sealed battery, heavyduty starter cables, automatic adjustment of brakes and clutch, no belts and tougher bulbs. Much of this is being achieved, he claimed. To give the manufacturers a kick in the right direction, Ryder has built 10 "ideal" trucks, featuring a wedge-shaped cab and skirted sides to cut air drag. Mr VicePresident reckons 25 to 35 per cent fuel saving.

Aerodynamics were a source of economy for which Volvo engineers expressed a good deal of enthusiasm. Their experiments with a variety of wind deflectors, some on the front of the semi-trailer, resulted in an average 4 per cent improvement in fuel consumption, they reported. While confirming similar sorts of results in the Ryder fleet ("We've never had better than 6 per cent"), Mr Paterson sounded a cautionary note about wind deflectors. "The advertising can seem misleading. It's hard to get consistent figures."

Perhaps one of the neatest methods of cutting maintenance costs came from a Dutch long-distance operator, Mr F. Gips, boss of Furtrans RV. "To guarantee no downtime at all I sell my Volvos before they reach 400,000km," he announced. That meant, he added, that to operate more economically he wanted Volvo to make an engine and transmission which lasted twice as long. In •the banter that ensued, Mr Batstone kept the pot stirring by throwing in the observation that he got 550,000 out of British diesels—and he meant

Tuners

Still, news came out of the argument which did much to confirm that Volvo must have some of the world's top diesel tuners. Hard-working engines give better fuel economy, says Volvo. Its next step is intercooling. The company is already running 460hp 12-litre trucks experimentally. All that power might not be needed, but there was a distinct leaning at the economy symposium to cutting the governed speed as a means of improving fuel economy and prolonging engine life.

Power in hand could afford Volvo the 1,800 to 2,000 rpm bracket much discussed at the symposium, without curtailing the performance which endears F88s to so many drivers. "Cut the revs, use a close-ratio box and specify a higher-geared axle" was a well-worn theme last week in Gothenburg. It seemed to indicate a theme for Volvo's future engineering policy too.