1 t is not just

Page 62

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the contrasting landscapes that make driving past Birmingham and bowl ing through

North Yorkshire two very different experiences. In the former you are minded to keep an eye on the speedometer—assuming you can get above 30mph on that section of the M6—since you know the beady eye of the law is likely to be upon you. In the countryside it might be easier, shall we say, to enjoy the scenery at speed— and not just because there is less congestion. Common sense, perhaps. After all, you would expect police to concentrate their efforts in certain areas.

' But under new guidelines from the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), things may be about to change. They set out what the police are meant to do if they catch you speeding, and the punishment you can expect in the courts.

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland ACPO says the idea of "zero tolerance" has never been on the agenda, because it was always considered unworkable. But this leaves several questions unanswered—not least how tolerant the authorities will now be.

Transport lawyer Stephen Kirkbright, of solicitors' practice Ford & Warren, says a zero tolerance policy might have been welcome. "Everyone knows where they stand, and it must make the roads safer. Equality of application is fair."

So does he think that there is uniformity of enforcement at the moment? "No, I don't," he says. "It is very difficult to achieve."

Another transport legal specialist. Jonathan Lawton, agrees. "You have to distinguish carefully between the public voice and the practicality of trying to achieve that. Whatever the public voice may be, the real voice is going to have to be 'they'll allow to%'."

And it is not only in terms of police on the road that tolerances vary. A rise in the use of technology does not necessarily mean parity for all in terms of detection or enforcement. It is public knowledge, for example, that Norfolk Constabulary's camera, which moves between seven sites, is set at a staggering 26mph above the speed limit. In all probability you would have to be driving recklessly (as opposed to merely fast) in order to be flashed.

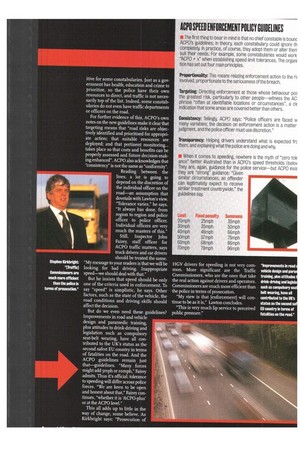

But just as this situation is unlikely to be unique, it must follow that other cameras in other areas of the UK will be set to trigger much closer to the limit. The cost of processing the film from speed cameras and mounting the follow-up enquiries is prohib itive for some constabularies. Just as a government has health, education and crime to prioritise, so the police have their own resources to direct, and traffic is not necessarily top of the list. Indeed, some constabularies do not even have traffic departments or officers on the road.

For further evidence of this, ACPO's own notes on the new guidelines make it clear that targeting means that "road risks are objectively identified and prioritised for appropriate action; that suitable resources are deployed; and that pertinent monitoring... takes place so that costs and benefits can be properly assessed and future decision-making enhanced". ACPO also acknowledges that "consistency" is not the same as "uniformity".

Reading between the lines, a lot is going to depend on the discretion of the individual officer on the road—an assumption that dovetails with Lawton's view. 'Tolerance varies," he says. "It always has done, from region to region and police officer to police officer. Individual officers are very much the masters of this."

Still, Inspector John Fairey, staff officer for ACP() traffic matters, says truck drivers and car drivers should be treated the same.

"My message to your readers is that we will be looking for bad driving. Inappropriate speed—we should deal with that." But he insists that speed should be only one of the criteria used in enforcement. To say "speed" is simplistic, he says. Other factors, such as the state of the vehicle, the road conditions and driving skills should affect the decision.

But do we even need these guidelines?

Improvements in road and vehicle design and paramedic training, plus attitudes to drink-driving and legislation such as compulsory seat-belt wearing, have all contributed to the UK's status as the second safest EU country in terms of fatalities on the road. And the ACPO guidelines remain just that—guidelines. "Many forces might add 5mph or iomph," Fairey admits. Thus it's official: tolerance to speeding will differ across police forces. "We are keen to be open and honest about that," Fairey continues, "whether it is ACP0-plus' or at the ACP() level."

This all adds up to little in the way of change, some believe. As Kirkbright says: "Prosecution of HGV drivers for speeding is not very common. More significant are the Traffic Commissioners, who are the ones that take the real action against drivers and operators. Commissioners are much more efficient than the police in terms of prosecution.

"My view is that [enforcement] will continue to be as it is," Lawton concludes.

"This is very much lip service to perceived public pressure." "Improvements In road vehicle design and para training, plus attitudes drink-driving and legisla such as compulsory sea belt wearing, have all contributed to the UN's status as the second sa EU country in terms of fatalities on the road."