'YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BUDGETARY CONTROL OF OPERATING COSTS

by Reg P. Block

WHEN the vehicle record form for the daily entries of vehicle /driver performance (CM last week) has been completed, preferably just after the end of each month, you can 'then produce a total for each appropriate column: days worked, units delivered/collected, hours worked, miles run, fuel and oil issued through agencies or bulk storage, and so on.

For the haulier, the total revenue earned and its make up enables him to compare at a glance the types of work that are the most lucrative or otherwise. This information is obtained simply by reference to "hours worked" and "miles run" and it is this knowledge on which his rates must be based irrespective of the method of charging out.

Performance budgets Budgetary control is often thought of as a method of controlling costs only, in order to take any corrective action when actual costs continue to exceed the budget agreed upon. Even so, it is also necessary to budget for vehicle/driver performance annually or quarterly depending on whether the nature of the work is regular or seasonal.

The budget can then be broken down to provide a monthly forecast for potential working days, units to be carried, number of drops, hours of work, estimated mileage, and mpg for fuel and oil — and, for the haulier, the estimated monthly revenue.

At this stage I have not referred to costs of operating as what you are planning is the budgetary control of performances first, and then, subsequently, the effect of deviations from the budget on total costs, unit costs (eg cost per ton), profits and /or product price. Utilization of time — days gainfully employed and of capacity — optimum loads -has a tremendous effect on the final outcome.

I am sorry to say that some elaborate costing systems overlook this important aspect. In the search for the reasons for increases in costs the tendency is to detect the areas like wages and repairs in which increases can be expected, and which are considered inevitable. The fact that an increase in the unit cost is due to under-utilization may go undetected because that possibility is not provided for in the system.

Monthly checks

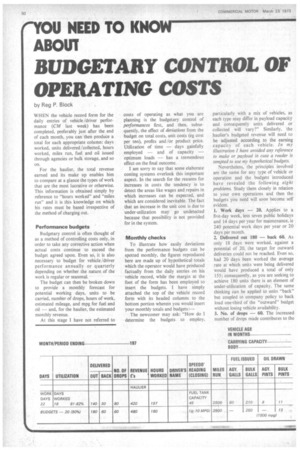

To illustrate how easily deviations from the performance budgets can be spotted monthly, the figures reproduced here are made up of hypothetical totals which the operator would have produced factually from the daily entries on his vehicle record, while the margin at the foot of the form has been employed to insert the budgets. I have simply attached the top of the vehicle record form with its headed columns to the bottom portion wherein you would insert your monthly totals and budgets:—

The newcomer may ask: "How do I determine the budgets to employ. particularly with a mix of vehicles, as each type may differ in payload capacity and consequently units delivered or collected will vary?" Similarly, the haulier's budgeted revenue will need to be 'adjusted according to the earning capacity of each vehicle. In my illustration I have avoided any reference to make or payload in case a reader is tempted to use my hypothetical budgets.

Nevertheless, the principles involved are the same for any type of vehicle or operation and the budgets introduced have revealed the following eight problems. Study them closely in relation to your own operations and then the budgets you need will soon become self evident.

1. Work days — 20. Applies to a five-day week, less seven public holidays and 14 days per year for maintenance, ie 240 potential work days per year or 20 days per month.

2. Delivered out 180 — back 60. As only 18 days were worked, against a potential of 20, the target for outward deliveries could not be reached. Even so, had 20 days been worked the average rate at which units were being delivered would have produced a total of only 155: consequently, as you are seeking to achieve 1.80 units there is an element of under-utilization of capacity. The same thinking can be applied to units –back" but coupled to company policy to back load one-third of the "outward" budget without losing vehicle availability.

3. No. of drops — 60. The increased number of drops made contributes to the under-utilization of payload capacity.

4. Revenue —haulier £480. See 1, 2 and 3 above because the same principles apply as for the own-account operator except that under-utilization of time or capacity hits the haulier directly through his pocket.

5. Hours worked — 180. The objective was to spread these hours over 20 days but this has been thwarted by the need to work more hours to offset the down-time suffered during the month.

6. Miles run — 2500. See 5 above but substitute miles for hours.

7. Fuel issued-budget — 10 mpg. A full vehicle fuel tank provided a cruising range of 450 miles and although the budget was exceeded, and with due regard to the average daily mileage, there was no justification for purchasing fuel from outside agencies, except for the inducements offered for the benefit of the driver.

8. Oil drawn-budget — 1500 mpg. Although the budget was exceeded the more serious aspect was revealed in writing up the vehicle record, when it was noticed that owing to a change of driver no sump replenishment had been recorded for two weeks. The driver was alerted when making a delivery and instructed to top up at an agency.

These imaginary situations, as any experienced operator will know are not so fanciful. Note the emphasis given to utilization, or the lack of it, and that I have not so far made one reference to costs; this is simply because the discrepancies evidenced between actual and budgeted performances will give you a fair indication that costs, particularly unit costs, are likely to be high. Not that you can jump to that conclusion without further evidence. Currently, however, the main purpose of this exercise is to give you the taste for budgetary control and minimum standards of performance.

The next and most important step is to examine those performance ingredients which warrant corrective action in order to ascertain if revisions to the budgets are justified, or remedial instructions to load planner and /or drivers — eg are agency fuel and engine oil top ups necessary? The objective must be to act promptly.

Operating costs — actual and budgets

The operating costs columns reproduced here — for comparative purposes I have introduced one for the haulier and one for the own-account operator —form the final portion of the whole vehicle record. Thus you have performances and costs on one monthly sheet.

To a certain extent the performances achieved, as illustrated earlier, are reflected in the operating costs. For example, you budgeted to use 250 gallons of fuel ex bulk storage at 30p per gallon, ie £75, whereas your driver purchased 60 gal ex agency at 35p per gallon and 210gal ex bulk, consequently the cost actually incurred was £84. The same tests can be applied to all the remaining cost ingredients and — except for insurance and establishment costs which are more costly for the haulier — the cost comparisons and budgets could apply equally to the own-account operator.

This is also true in respect of the utilization of time and capacity, although the haulier will need to be far more vigilant in this area of operation if he aims to survive.

Don't amend budgets !

Budgeted costs for own account operators or hauliers should be employed by each to -determine haulage rates or product price but don't amend the budgets to match the "actual" performances and costs.

The own-account operator has included the cost of two new tyres plus abnormal repair costs in the one month; the haulier has not incurred any expenditure on these items. Though his actual and budgeted costs do not appear to be greatly different, this is accounted for by the fact that his expenditure on fuel, oil, insurance, establishment costs and drivers' wages tend to offset the budgets built-in for tyres and maintenance.

The relatively small cost involved in containing or reducing operating costs is infinitely more rewarding than cost inflation owing to inefficiency with a consequent loss of business. Clearly, the main objective for the haulier is to maximize profits through the provision of good customer service at the optimum cost; for the own-account operator it is to provide good customer service within the transport cost built into the product or service price.

There are nine items of operating costs and a driver can influence all except road tax. Get the other eight ingredients right and you will have found the recipe to success.