OLDHAM HARMON

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 79

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By JOHN F. MOON

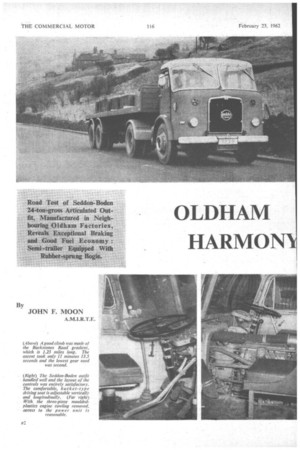

AN articulated vehicle can have a personality. Some outfits seem destined to be ill-matched for the whole of their usable lives—others seem to be compatible from the word "go.". I have just been testing one of the latter, a Seddon-Boden 24-ton-gross eight-wheeler which distinguished itself by having the safest braking of any heavy artic yet tested by The Commercial Motor, truly

amenable handling characteristics and a low rate of fuel consumption.

In the case of the vehicle I tested, it was mere coincidence that the tractive unit and semi-trailer were made in neighbouring factories, The two components had not been " introduced" to each other until the day I arrived in Oldham to start the test, and the semi-trailer was not loaded up until after 1 had collected the vehicle. There was no collusion, therefore, between these two .makers in a deliberate endeavour to secure optimum braking efficiency, for example. The good retardations recorded were purely a result of sound basic design principles on the part of both manufacturers. There is a lesson to be learned here!

The tractive unit employed for these tests was a standard Seddon SD.4 9-ft.-wheelbase model, with Gardner 6LX diesel engine, David Brown 657 six-speed overdrive-top gearbox, Kirkstall double-reduction rear axle and B.T.C. S.A.E./S.M.M.T. fifth-wheel coupling. The kerb weight of• the .unit was 5 tons 2.5 cwt., a reasonable figure for a machine of this type and 7.25 cwt. lower

than that of a Cummins-engined SD.4 tractive unit tested in August, 1959.

This Seddon had been built to the order of Henry Smith (Construction Engineers), Ltd., WinsfOrd, Cheshire; who kindly, delayed taking delivery of the vehicle so that I might conduct this test. Henry Smith require it for operation at 30 tons gross train weight, and because of this it had a rather low rear-axle ratio-7.01 to 1—alternative ratios available in this chassis being 6.28, 7.95 and .9.17 to 1. The ultra-low-ratio axle would only be used when the SD.4 is required for operation at its maximum rating of 32 tons and under the arduous overseas

conditions. .

The specification of the tractive unit follows conventional lines. It has a robust and straightforward bolted chassis, frame, the side members of which are 0.3125 in. thick, with a maximum depth of 10.875 in. and 3-in.-wide flanges. There are four channel-section cross-members, secured by 0.5-in. bolts. The semi-elliptic springs at both axles are 3 in. wide, the front springs being 48 in. long and the rears 54 in. long. Telescopic dampers can be supplied for the front axle and were on the test vehicle.

A dual-circuit air-pressure braking system is employed, this being controlled by a dual E valve, so that the brakes of the front axle and the semi-trailer are on one circuit, with the driving axle on a separate circuit. Power is supplied by a Tu-Flo 500 twin-cylinder water-cooled compressor with a piston displacement of 12 cu. ft. per minute. A conventional brake pedal is fitted, and the handbrake lever is a Neate NBC 8 three-stroke multi-pull unit.

All-steel Landing Gear

Michelin D.20 Metallic tyres were fitted, at the request of the customer, and the chassis was mounted with the standard Seddon plastics-panelled cab as currently used throughout their heavy-vehicle range.

The semi-trailer was a standard Boden 17/1010/H 26-ft.-long tandem-axle unit with Eaton-Hendrickson rubber-sprung bogie and timber-decked body. The recently introduced lightweight all-steel landing gear was fitted, this offering considerable cost advantages compared with fight-alloy gears. This Boden design is particularly robust in construction, despite which its weight is comparatively low. The chassis frame has 0.3125-in.-thick side-members which have a maximum depth of 15 in., tapering to 7 in. over the rubbing plate. In the area of this reduced section cruciform bracing is incorporated to give frame rigidity.

Four 0.1875-in.-thick pressed cross-members are welded to the side-members and, in addition, there is a 5-in.-diameter tube with flanged ends bolted to the main members and joining the upper ends of the landing-gear tubes. The Hendrickson bogie, which incorporates four rubber " load cushions" and rubber-bushed torque arms, so eliminating the need for suspension greasing, has two 10-ton-capacity axles with straight tubular beams. These are rubber-rnounted to the suspension walking beams, an arrangement which permits a high degree of inter-axle articulation, again without the need for lubrication. Girling two-leading-shoe brakes, actuated by Bendix-Westinghouse F4 diaphragm-type units, are employed, and these give a total lining area of 724 sq. in.

Having weighed the unladen tractive unit and semitrailer, I asked for a test load of about 15 tons to be put on the semi-trailer. By the time supporting timber baulks had been added, however, the imposed load totalled 15 tons 10.75 cwt., so the gross train weight throughout the test was 9.5 cwt. above the British legal maximum. Because the fifth-wheel coupling on the tractive unit had been positioned for use with a different semi-trailer, the outfit was 7 in, above the permissible legal limit.

As the roads were dry I decided to do the brake tests first, and curiosity made me check the efficiency of the semi-trailer air-brake system before making the footbrake stops. These semi-trailer brake tests were made by applying the hand reaction valve in the cab at 20 m.p.h., and such was the power of the brakes that repeated Tapley meter figures of 37 per cent. were obtained, all the semi-trailer wheels locking before the outfit came to rest. This retardation is exceptional, and warned me to expect some pretty spectacular results from the footbrake. I was not disappointed. Full application of the brake pedal at 30 m.p.h. resulted in an average sto,uping distance of 50.75 ft., whilst the Tapley meter indicated an average maximum retardation of 80.5 per cent. All the wheels of the outfit except the off-side front locked, and on one occasion there was slight pulling to the right, but generally the vehicle came to a standstill in a smooth and stable manner. Furthermore, in view of the power of these brakes. I could be thankful that the headboard and its supporting members were strong enough to hold the load.

The retardation from 20 m.p.h. was equally impressive, although the average rate of stopping was not quite so high as when pulling up from 30 m.p.h. Nevertheless, it was quite obvious that this outfit's braking system was well above average for a vehicle of this weight and type. It has set a standard that other manufacturers should try to emulate.

Having proved the power of the brakes with the drums cold, I then took the outfit to Buckstones Road, Shaw, a hill with an average gradient of I in 12, which is 1.25 miles long. These gradient tests commenced by a non-stop ascent made in an ambient temperature of 5° C. (41° F.). Before making the climb I measured the engine-coolant temperature, and this was 54° C. (130° F.). The ascent was quite fast for a vehicle of this weight and occupied 11 minutes 13.5 seconds. At no time did the road speed drop below 6 m.p.h., and this was while running on the governor in second gear, this ratio being used for

4 minutes 41 seconds The exhaust was clean the whole time.

Fade Resistance

Fade resistance was checked by coasting down the hill in neutral, the speed being kept down to 20 m.p.h. or thereabouts by use of the footbrake. The descent lasted 5 minutes 4 seconds, and at the bottom of the hill I applied the footbrake hard from 20 m.p.h.: the wheels on the rear axle of the semi-trailer locked and the Tapley meter showed the maximum retardation to have been 54 per cent. This is only 22.5 per cent. less than ,the maximum retardation with cold drums; as the tractive unit had run less than 30 miles since it was built (the brakes were thus not bedded in), it can safely be said that the outfit had commendable fade resistance. By the time this stop was made the air pressure had dropped to 80 p.s.i., the normal pressure being 110 p.s.i., so that had the pressure been higher even better retardation would have resulted.

The Seddon-Boden was then driven back to the steepest part of the hill, where the gradient is 1 in 61. Here it was stopped and the tractive-unit handbrake, the semi-trailer hand-control air brake and the semi-trailer parking brake were each applied separately in turn: all the brakes were shown to be powerful enough to hold the outfit by themselves—another praiseworthy feature of the braking systems of the two units.

Following these hill-holding tests, I managed to make a restart in second gear. Although this manceuvre was carried out smoothly, I found it necessary to slip the elutch momentarily to get the outfit started, but once on the move the engine pulled away confidently, if slowly.

Economical Running

Fuel-consumption figures were taken over a six-mile return circuit along The Broadway, Chadderton. In addition to containing one or two deceptively severe gradients, this stretch of road has the added obstacles of six sets of traffic lights and one roundabout. On this occasion I was lucky with the lights, however, and managed to achieve an average speed of 25.7 m.p.h. without exceeding 32 ni.p.h. at any time. The use of 5.275 pints of fuel indicated a consumption rate of 9.1 m.p.g., which serves to emphasize yet again the Gardner 6LX's reputation for economical running.

Because of the low axle ratio and the good low-speed torque of the 6LX, acceleration from a standstill up to 20 m.p.h. was appreciably better than that between 20 and 30 m.p.h., although even so the time taken to reach 30 m.p.h. was quite short. Second gear was used when starting off, and the change up to fifth (direct) was made at 20 m.p.h., fifth gear itself being usable up to just over 30 m.p.h., whilst the top-gear speed is 42 m.p.h.

Again because of the gearing and engine-torque characteristics, there was a marked difference when accelerating in direct drive between the time taken to reach 20 m.p.h. from 10 m.p.h. and that required to reach 30 m.p.h. from 20 m.p.h. In this case also, though, the times recorded were good.

Drivers of this Seddon-Boden outfit should have little to complain about. The vehicle was light to handle, even at low speeds, and the gear-change action was good. The brakes were fully progressive and engine poise was low, the cowl being a three-piece plastics moulding incorporating a hinged trap to give access to the oil filler on the engine.

Despite the short wheelbase the tractive unit rode smoothly, although humpy road surfaces could create. a certain amount of steering-wheel shake. The range of all-round vision was entirely satisfactory, and I was pleased to see that sensibly large rear-view mirrors were standard.