Socialism on wheels?

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The nationalisation of transport in 1948 was eventually destined for failure, but in many ways it was a forerunner of things to come

Words: Dave Young / Images: supplied by Bob Tuck Think back to Britain in 1948, despite rationing remaining in force and the hardest winter in living memory, many people were optimistic. Clement Atlee’s new Labour government had established the NHS, there was free education and the coal mines had just been nationalised. The nation had become accustomed to centralised planning during WW2 and in 1947 the British Transport Commission (BTC) was created to provide “an eficient, adequate, economical and properly integrated system of public inland transport and port facilities within

Great Britain for passengers and goods” . It began by nationalising the railways, which were such a pre-war business basket case there was little alternative, followed by the docks, buses, canals and – due to an historic quirk – Thomas Cook travel agents. The BTC was one of the largest industrial organisations in the world, employing nearly 688,000 people.

Next on the list was road transport, pushed strongly by the trade unions, Herbert Morrison (the legislation’s architect and Peter Mandelson’s grandfather) set up British Road Services (BRS). His cabinet colleague Ernest Bevin had named the Post Ofice as a shining example of nationalisation’s beneits, blissfully unaware that much of its road transport was subcontracted to a private concern, McNamara.

‘No government interference’

Lloyd George had tried and failed with a similar scheme in 1919, and now the RHA fought Labour’s plans for state-controlled haulage side by side with Winston Churchill. Tate & Lyle’s Mr Cube character, created when the company was threatened by the formation of British Sugar, was at the forefront of anti-nationalisation campaigns.

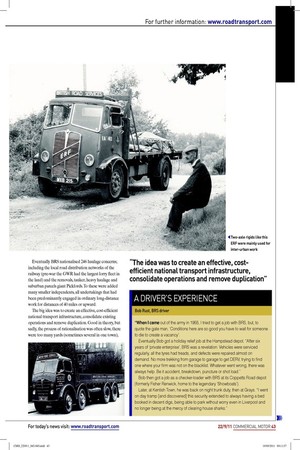

“No government interference” was the cry, a little hypocritically perhaps because the haulage industry had always been happy to beneit from indirect, taxpayerfunded state spending such as the cheap ex-army lorries, that looded the market after WW1, driver training in the armed services, and the vast expansion of the arterial road and bypass network used to create jobs during the 1930s depression. All these were conveniently overlooked by operators, many of whom did very well from the compulsory purchase of their trucks and yards, either accepting a sinecure as a BRS depot manager or setting up in competition. Eventually BRS nationalised 246 haulage concerns; including the local road distribution networks of the railway (pre-war the GWR had the largest lorry leet in the land) and the removals, tanker, heavy haulage and suburban parcels giant Pickfords. To these were added many smaller independents, all undertakings that had been predominantly engaged in ordinary long-distance work for distances of 40 miles or upward.

The big idea was to create an effective, cost-eficient national transport infrastructure, consolidate existing operations and remove duplication. Good in theory, but sadly, the process of rationalisation was often slow, there were too many yards (sometimes several in one town), and a failure to integrate resources. The BRS depot network was intended to ensure return loads, but there was still too much empty running. Instead of co-operating, many depots and even regions iercely guarded their own territory and competed against each other for custom.

The initial strategy was to send ‘distance trafic’ by rail and cross-country loads by truck. For trunking work, BRS standardised on the (then) maximum size vehicle permitted, a 22-ton GVW four-axle rigid. Artics were rare; it was mainly smaller vehicles that were used on inter-urban duties. Rigids could only pull a drawbar trailer if a second ‘trailer man’ was present in the cab, increasing the cost. The maximum speed for vehicles over three tons ULW (unladen weight) was 20mph.

Improved efficiency

To cope with a post war shortage of new trucks – most were being built for export to assist our ailing balance of payments – BRS developed its own at a wholly-owned factory it had acquired as part of bus nationalisation.

However, as late as 1966 it was buying 60 AEC chassis a month. With 4,000 new vehicles and a lot of former military men in management, eficiency improved. BRS invested in mechanical handling (although handballing and rope & sheeting predominated) and the working life of vehicles dropped from 12 to eight years. As driver Bob Rust recalls: “It’s soon forgotten that BRS vehicles were the irst to have cab heaters.” Large contract leets also operated in customer colours, such as Kelloggs, Whitbread, Grimsby Fish and International Harvester, and during the1950s Ian Allan published the BRS spotter’s guides: an alternative to collecting train numbers and anticipating the Eddie Stobart fan club.

And let’s not forget the role of animals. Apart from the ‘cycling ferret’ cab door logo (named Penelope, although no one can recall why), BRS recruited real dogs (mainly terriers) from Battersea Dogs Home to sit on the tailboard of local C&D vans and deter theft. It also inherited a considerable number of horses and stables (one became Camden Market), while contemporary inancial accounts list food for rat-catching ofice cats.

Over the years the mixed fortunes of BRS luctuated with the economy and changes of government. Partly denationalised in 1952 and again in 1955 (the BTC was criticised as an overly bureaucratic system of administering transport services), the number of specialist groups was cut to four. In a typically British fudge BRS competed with resurgent private hauliers, many run by those whose original irms had been nationalised.

The return of Labour to power and Mr Beeching’s railway cuts saw something of a reversal of BRS fortunes during the 1960s.

Foreign marques

In the 1970s some regions , to the horror of the unions but the delight of drivers, bought foreign marques, including Volvo, Scania and Mercedes-Benz. BRS even set up an overland tilt service to Iran hauled by Leyland Marathons. In 1969 BRS was renamed the National Freight Corporation then privatised in 1982 when Margaret Thatcher’s government sold NFC to its employees. In 2000 it merged with Ocean Group to form Exel and was eventually acquired by DHL.

BRS Parcels was rebranded Roadline and after a management buy-out in 1997 became Lynx Express.

Pickfords was sold in 1999 to Allied Van Lines, then again in 2002 to Sirva.

BRS truck rental was acquired by Volvo/Renault Trucks LTK.

Haulage nationalisation was never really a leftward lurch to command and control economics. In many ways the BRS attempt to build a road transport infrastructure was ahead of its time – just look at the pallet networks and recent haulage partnerships Harlequin and Jigsaw. Attempting to impose central planning on the very embodiment of freebooting capitalist endeavour was never going to work for bosses, but BRS did much to improve the terms and conditions of drivers. ■