DRIVERS' PAY: PART TWO

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The spectre of low pay is crippling the haulage industry. Battered by meagre wages in return for punishing work schedules, HGV drivers are fast becoming a scarce commodity. In the second of a two-part report, Nicky Clarke looks at an industry that may well have shot itself in the foot.

Iii the world of road transport the phrase you just can't get the staff these days" is likely to provoke a surly response rather than the usual chuckle. It just isn't funny anymore. The shortage of drivers, particularly artic drivers, that hit certain parts of the country 12-18 months ago is now a nationwide problem.

Winning the work is a waste of time if there's no one to drive the wagons. Drivers are leaving the industry in droves and the number of HGV driving test applicants has almost halved over the past seven years to 47,000 this year.

More than 66% of the 1,000 respondents to the Road Haulage and Distribution Training Council's recent Skills for the Future survey are having problems recruiting drivers, particularly in the C+E category. The worst-hit areas include London, the Thames Valley, South Glamorgan, Leeds and the South Midlands.

It's not surprising that no one wants to work in transport: a raft of surveys published over recent months reveal that driving is seen as a low-status job. For those brave souls who do want to embark on a career in transport these surveys give a grim idea of what they can expect to earn, and what hours they will have to work.

A Government-commissioned report has just defined driving as "semi-routine" (which formerly meant semi-skilled). The Economic and Social Research Council Review of Government Social Classifications places lorry drivers alongside traffic wardens and assembly-line workers, and below dri ving instructors, builders and plumbers. The decision to place drivers here is based on their

employment relations, which were found to be similar to those in other semiskilled jobs.

Sadly, from the drivers' point of view, the law of supply and demand has yet to expand their pay packets. A Transport and General Workers Union survey of pay and hours published during the summer found that 60% of transport workers earn less than £300 a week.

There's no shortage of evidence to indicate that terms and conditions for most drivers are extremely poor. Some 57% of the 1,800 respondents to the T&G survey said they are paid less than £5 an hour. Delivery drivers were found to be the worst paid, with 74% earning below £5 an hour. Even highly skilled tanker drivers are not immune: 14% of them also get less than £5 an hour.

One of the most commonly cited reasons for the shortage of recruits is the long hours they need to work in order to earn decent money. According to T&G regional industrial organiser Rod Goodwin, the average truck driver works 50 hours a week: workers in other industries average around 45 hours.

Half the respondents to the T&G survey said they work 10-15 hours overtime a week. That's against the backdrop of the West Midlands Joint Industrial Council agreement, introduced at the beginning of the year, which is meant to empower drivers to limit their hours to 50 a week.

"I'm sure they're doing more hours," says T&G regional organiser Hugh Lowry, "The culture of long hours is a difficult nut to crack but this agreement gives the drivers the tool to do it." Working overtime is ingrained and historical, he adds. They start out to get their money up to a decent level and they get locked in."

So it seems there's no mystery behind the driver shortage. If the industry really wants to attract new drivers, and hold onto the ones it has, something must be done about terms and conditions of employment— described by RHDTC chief executive Ian Hetherington as a "fundamental plank that has got to be attractive enough to get drivers and keep them."

But this won't provide the whole answer, accord ing to United Road Transport Union secretarygeneral David Higginbottom. "Improving pay and conditions is good for people in the industry now but it won't persuade people who have left to come back," he says. "We can all play a part I'd like to see a common agreement as to what kind of reward package drivers ought to get theoretically." He believes a single union stands more chance of achieving a better deal for drivers. "Weak trade unionism has not served anyone well," he asserts.

The situation could be improved immediately, says Higginbottom, if every haulier committed himself to training one driver. "We need to bring new people into the industry in an effective and controlled way," he says.

Hetherington holds similar views on training. "There has to be a new mentality," he says. "There is a spark of expectation in most people and they wish to develop themselves."

Dave Green, head of training at the Freight Transport Association, suggests that companies should look at ways of developing career paths for manual workers. "You can't become a driver until you're 21 but employees could start off in the warehouse, move on to fork-lift truck operations, then on to rigids and then to HGVs," he says. "There's evidence to suggest that hitherto companies have not considered this."

Hetherington is also certain that multi-skilling is part of the answer. "The HGV driving test that was well earned in 1972 is probably not an adequate test of one's ability and competence to operate effectively in the year 2000," he says. "The transport of goods embraces many things other than driving. There are other road users, customers, and there's information technology."

The issue of low pay and long working hours has always been at the root of driver dissatisfaction. Drivers' unions and employers failed to agree on the introduction of a 48-hour working week. The EC stepped in, ruling that the 48-hour limit would, indeed, cover all employed and self-employed drivers.

But this plan is likely to take years to come into effect. In the meantime, some short-term action to stop qualified drivers leaving the industry, and to attract recruits, is urgently needed.

ET by Nicky Clarke.

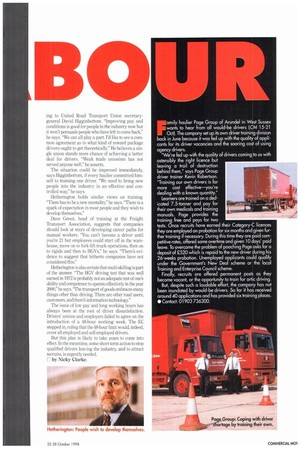

_amily haulier Page Group of Arundel in West Sussex

wants to hear From all would-be drivers (CM 15-21 Oct(, The company set up its own driver training division back in June because it was fed up with the quality of applicants for its driver vacancies and the soaring cost of using agency drivers. "We're fed up with the quality of drivers coming to us with ostensibly the right licence but leaving a trail of destruction behind them," says Page Group driver trainer Kevin Robertson. "Training our own drivers is far more cost effective—you're dealing with a known quantity." Learners are trained on a dedicated 7.5-tanner and pay for their own medicals and training manuals. Page provides the training free and pays for two tests. Once recruits have earned their Category-C licences they are employed on probation for six months and given further training if necessary. During this time they are paid competitive rates, offered some overtime and given 10 days' paid leave. To overcome the problem of poaching Page asks for a deposit of 2520 which is repaid to the new driver during his 26-weeks probation. Unemployed applicants could qualify under the Government's New Deal scheme or the local Training and Enterprise Council scheme.

Finally, recruits are offered permanent posts as they become vacant, or the opportunity to train for artic driving.

But, despite such a laudable effort, the company has not been inundated by would-be drivers. So for it has received around 40 applications and has provided six training places.

• Contact: 01903 736300.